Slavery in Malta

Sources dating back to when the islands were under Arab rule during the Middle Ages attest to the presence of slavery but lack details regarding the slaves' ethnic and religious backgrounds.

Around the same time, there were Maltese people enslaved in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire after being captured during attacks on the islands or on Christian shipping, including in raids by the Barbary corsairs.

After the Roman Republic captured Malta from the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War in 218 BC, prisoners who were not of noble birth were sold as slaves in Lilybaeum, Sicily.

[9] The majority of slaves in Hospitaller Malta were acquired during corsair raids on enemy shipping or coastal targets, and this economic-military model allowed the system of slavery to be maintained from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

[10] Malta's capital Valletta has been described as one of the Mediterranean's key centres for corsairing during the early modern era, similar to Livorno and their Muslim counterpart Algiers.

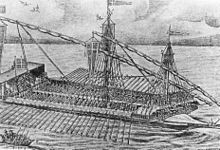

[11] In addition, the Hospitallers maintained their own fleet of galleys and other vessels which would be sent out each year to pursue Muslim merchant shipping and raid undefended coastal settlements.

[11] By the 18th century, corsairing was on the decline in much of the Mediterranean, but the practice persisted in Malta even as other ports reoriented themselves towards safer and more lucrative economic activities such as trade.

[11][13][14][15] The Hospitallers used the pretext of a perpetual holy war against Islam as a justification for their corsairing activities,[11] but in practice captains of ships were ordered to sail the seas and plunder for profit.

[8] They were auctioned off at a public slave market in Valletta, which was situated at Piazza San Giorgio, the city's main square in front of the Grandmaster's Palace.

[12] An example of how the slave trade operated in practice can be seen in the events that occurred after the 1685 siege of Coron in the Peloponnese, in which the Hospitallers supported the Venetians against the city's Ottoman defenders.

Official figures indicate that after the city surrendered, 1,336 Turkish and Jewish inhabitants were taken as slaves and were divided between the various members of the Christian coalition, with the Hospitallers taking 223 captives.

[27] Slaves performed a wide variety of duties, with the most robust being destined for the galleys, while others remained on land and worked in domestic roles, as servants, cooks, and workers.

[14] During the building of fortifications, slaves were usually assigned menial tasks such as removal and carting away of rubble, while construction was generally done by skilled workers employed by contractors.

[32] A few hundred Muslim slaves captured during the 1565 Great Siege of Malta were involved in the construction of the new capital city of Valletta, including the excavation of the fortress's ditch.

[32] Examples of Maltese slave owners from the Hospitaller period include the family of architect Girolamo Cassar,[33] chemist and benefactor Caterina Vitale,[32] landowner Clemente Tabone,[34] and noblewoman Cosmana Navarra.

[8] Slaves were subjected to public floggings while tied to a stone column at Piazza San Giorgio in Valletta, and were sometimes paraded around the city on a cart while being repeatedly burnt with a branding iron.

An over-representation the latter compared to their relatively low numbers may indicate that for women, union with a Maltese man might have been a fairly frequent outcome of their state of slavery.

[7] One example of former slaves and their children becoming part of Maltese society is architect Carlo Gimach, whose ancestor was a Palestinian Muslim who became Christian after the Hospitallers enslaved him.

[45] A charity which raised funds for ransoming Maltese slaves held in Muslim territories, the Monte della Redenzione degli Schiavi, was set up in 1607 by Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt.

Others only regained their freedom after many years in Malta, with elderly slaves or those who were no longer fit to work sometimes being freed or sold for nominal sums and allowed to return to their native countries.

On 29 June 1531,[47] less than a year after the Hospitallers' arrival in Malta, 16 slaves escaped the ramparts of Fort St. Angelo and then opened the doors of the prisons and killed the guards.

After Malta formally became British colony in 1813, de facto slavery was still practiced, with a notarial deed by a certain Michelina Briffa making reference to "her two slaves" Paolo and Tomasa being dated as late as 11 March 1814.

While they were not generally referred to as slaves in quarantine registers, they were allegedly sold as servants to the Maltese and to British subjects, as claimed in an 1812 letter sent by a man named G. Macintosh to abolitionist Zachary Macaulay of the African Institution.

[55] When Malta was part of the Kingdom of Sicily and during Hospitaller rule, the islands were subjected to occasional razzias and attacks by Arabs from North Africa, and later by Barbary corsairs and the Ottoman Empire.

Between September and October 1429, Malta was invaded by the Hafsids, and although the attackers were unable to take the fortified city of Mdina, the nearby suburb of Rabat was destroyed.

The only inhabitants who avoided being enslaved were a few hundred people who managed to escape by scaling down the Castello's walls, along with 40 elderly men, a pregnant woman and a monk who were spared by the Ottomans.

[11][63][a] The last major attack was a raid on southern Malta in July 1614, when an Ottoman fleet landed at Marsaskala Bay and proceeded to pillage the area around Żejtun before being repelled by a Maltese and Hospitaller militia.

An example of this can be seen in the case of Dionysius Fiteni, who was liberated in 1732 after 20 years of slavery when the galley he was working on was attacked and captured by a Hospitaller vessel commanded by Jacques-François de Chambray.

Conversion to Islam was also a regular occurrence among Maltese enslaved abroad, although those who converted and subsequently managed to make their way back home would face the Inquisition tribunal upon their return to Malta.

[27] A slave narrative written by Macuncuzade Mustafa Efendi, an Ottoman qadi who was captured by the Hospitaller fleet off Cyprus in 1597 and was enslaved in Malta until he was ransomed in 1600, has also been published.