Slavic paganism

Many traces of Slavic paganism are thought to be left in European toponymy, including the names of settlements, rivers, mountains, and villages, but ethnologists such as Vitomir Belaj warn against hasty assumptions that the toponyms truly originate in pre-Christian mythological beliefs, with some potentially being derived from common vocabulary instead.

[12] Twentieth-century scholars who pursued the study of ancient Slavic religion include Vyacheslav Ivanov, Vladimir Toporov, Marija Gimbutas, Boris Rybakov,[13] and Roman Jakobson, among others.

Rybakov is noted for his effort to re-examine medieval ecclesiastical texts, synthesizing his findings with archaeological data, comparative mythology, ethnography, and nineteenth-century folk practices.

[citation needed] In the times preceding Christianisation, however, some Greek and Roman chroniclers, such as Procopius and Jordanes in the sixth century, sparsely documented some Slavic concepts and practices.

[16] It has been argued that the essence of early Slavdom was ethnoreligious before being ethnonational; that is to say, belonging to the Slavs was chiefly determined by conforming to certain beliefs and practices rather than by having a certain racial ancestry or being born in a certain place.

[21] According to Adrian Ivakhiv, the Indo-European element of Slavic religion may have included what Georges Dumézil studied as the "trifunctional hypothesis", that is to say a threefold conception of the social order, represented by the three castes of priests, warriors and farmers.

[22] As attested by Helmold (c. 1120–1177) in his Chronica Slavorum, the Slavs believed in a single heavenly God begetting all the lesser spirits governing nature, and worshipped it by their means.

[24] Before its conceptualisation as Rod, Rybakov claims, this supreme God was known as Deivos (cognate with Sanskrit Deva, Latin Deus, Old High German Ziu and Lithuanian Dievas).

[27] For instance, Leshy is an important woodland spirit, believed to distribute food assigning preys to hunters, later regarded as a god of flocks and herds, and still worshipped in this function in early twentieth-century Russia.

This root also gave rise to the Vedic Parjanya, the Baltic Perkūnas, the Albanian Perëndi (now denoting "God" and "sky"), the Germanic Fjörgynn and the Greek Keraunós ("thunderbolt", rhymic form of *Peraunós, used as an epithet of Zeus).

[39] Adam of Bremen (c. 1040s–1080s) described the Triglav of Wolin as Neptunus triplicis naturae (that is to say, "Neptune of the three natures/generations"), attesting the colours that were attributed to the three worlds, also studied by Karel Jaromír Erben (1811–1870): white for Heaven, green for Earth and black for the underworld.

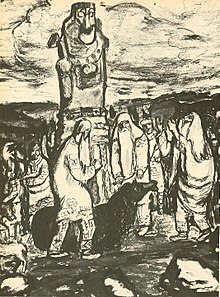

[43] These three-, four- or many-headed images, wooden or carved in stone,[35] some covered in metal,[23] which held drinking horns and were decorated with solar symbols and horses, were kept in temples, of which numerous archaeological remains have been found.

These ritual banquets are known variously, across Slavic countries, as bratchina (from brat, "brother"), mol'ba ("entreaty", "supplication") and kanun (short religious service) in Russia; slava ("glorification") in Serbia; sobor ("assembly") and kurban ("sacrifice") in Bulgaria.

[5] The priests (volkhvs), who kept the temples and led rituals and festivals, enjoyed a great degree of prestige; they received tributes and shares of military booties by the kins' chiefs.

They came into contact with Christianity during the reign of emperor Heraclius (610-641), continued by Rome, and baptization process ended during the rule of Basil I (867-886) by Byzantine missionaries of Constantinople Cyril and Methodius.

[54] According to scholars, Vladimir's project consisted of a number of reforms that he had already started by the 970s, and which were aimed at preserving the traditions of the kins and making Kiev the spiritual centre of East Slavdom.

[55] Perun was the god of thunder, law and war, symbolised by the oak and the mallet (or throwing stones), and identified with the Baltic Perkunas, the Germanic Thor and the Vedic Indra among others; his cult was practised not so much by commoners but mainly by the aristocracy[citation needed].

[53] Mokosh, the only female deity in Vladimir's pantheon, is interpreted as meaning the "Wet" or "Moist" by Jakobson, identifying her with the Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") of later folk religion.

[53] The high clergy repeatedly condemned, through official admonitions, the worship of Rod and the Rozhanitsy ("God and the Goddesses", or "Generation and the generatrixes") with offerings of bread, porridge, cheese and mead.

[3] According to the Primary Chronicle, after the choice was made Vladimir commanded that the Slavic temple on the Kiev hills be destroyed and the effigies of the gods be burned or thrown into the Dnieper.

In the core regions of Christianisation themselves the common population remained attached to the volkhvs, the priests, who periodically, over centuries, led popular rebellions against the central power and the Christian church.

[62] V. G. Vlasov quotes the respected scholar of Slavic religion E. V. Anichkov, who, regarding Russia's Christianisation, said:[63] Christianization of the countryside was the work, not of the eleventh and twelfth, but of the fifteenth and sixteenth or even seventeenth century.According to Vlasov the ritual of baptism and mass conversion undergone by Vladimir in 988 was never repeated in the centuries to follow, and mastery of Christian teachings was never accomplished on the popular level even by the start of the twentieth century.

[64] This occurred as an effect of a broader complex of phenomena which Russia underwent by the fifteenth century, that is to say radical changes towards a centralisation of state power, which involved urbanisation, bureaucratisation and the consolidation of serfdom of the peasantry.

This was among the changes that led to a schism (raskol) within Russian Orthodoxy, between those who accepted the reforms and the Old Believers, who preserved instead the "ancient piety" derived from indigenous Slavic religion.

[72] In the opinion of Norman Davies,[73] the Christianisation of Poland through the Czech–Polish alliance represented a conscious choice on the part of Polish rulers to ally themselves with the Czech state rather than the German one.

[5] Ethnography in late-nineteenth-century Ukraine documented a "thorough synthesis of pagan and Christian elements" in Slavic folk religion, a system often called "double belief" (Russian: dvoeverie, Ukrainian: dvovirya).

[79] Bernshtam challenges dualistic notions of dvoeverie and proposes interpreting broader Slavic religiosity as a mnogoverie ("multifaith") continuum, in which a higher layer of Orthodox Christian officialdom is alternated with a variety of "Old Beliefs" among the various strata of the population.

[81] Belief in the holiness of Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") is another feature that has persisted into modern Slavic folk religion; up to the twentieth century, Russian peasants practiced a variety of rituals devoted to her and confessed their sins to her in the absence of a priest.

For instance, the Christmas period is marked by the rites of Koliada, characterised by the element of fire, processions and ritual drama, offerings of food and drink to the ancestors.

The earliest wooden churches in shape and plan were a square or oblong quadrangle with a tower-shaped dome planted on it, similar to those that were placed in ancient Russian fortresses.