Small-world experiment

Guglielmo Marconi's conjectures based on his radio work in the early 20th century, which were articulated in his 1909 Nobel Prize address,[2][failed verification] may have inspired[3] Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy to write a challenge to find another person to whom he could not be connected through at most five people.

Mathematician Manfred Kochen and political scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool wrote a mathematical manuscript, "Contacts and Influences", while working at the University of Paris in the early 1950s, during a time when Milgram visited and collaborated in their research.

Milgram took up the challenge on his return from Paris, leading to the experiments reported in "The Small World Problem" in the May 1967 (charter) issue of the popular magazine Psychology Today, with a more rigorous version of the paper appearing in Sociometry two years later.

Michael Gurevich had conducted seminal work in his empirical study of the structure of social networks in his MIT doctoral dissertation under Pool.

The simulations, running on the slower computers of 1973, were limited, but still were able to predict that a more realistic three degrees of separation existed across the U.S. population, a value that foreshadowed the findings of Milgram.

This was the same phenomenon articulated by the writer Frigyes Karinthy in the 1920s while documenting a widely circulated belief in Budapest that individuals were separated by six degrees of social contact.

This observation, in turn, was loosely based on the seminal demographic work of the Statists who were so influential in the design of Eastern European cities during that period.

Milgram's study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately three friendship links, on average, without speculating on global linkages; he never actually used the phrase "six degrees of separation".

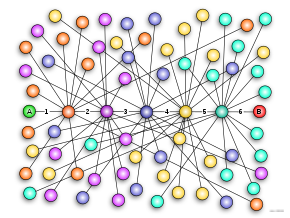

An alternative view of the problem is to imagine the population as a social network and attempt to find the average path length between any two nodes.

There are a number of methodological criticisms of the small-world experiment, which suggest that the average path length might actually be smaller or larger than Milgram expected.

[citation needed] Smaller communities, such as mathematicians and actors, have been found to be densely connected by chains of personal or professional associations.

For instance, Peter Dodds, Roby Muhamad, and Duncan Watts conducted the first large-scale replication of Milgram's experiment, involving 24,163 e-mail chains and 18 targets around the world.

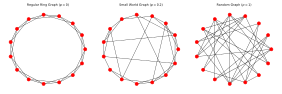

[citation needed] In 1998, Duncan J. Watts and Steven Strogatz from Cornell University published the first network model on the small-world phenomenon.

[14] The research was originally inspired by Watts' efforts to understand the synchronization of cricket chirps, which show a high degree of coordination over long ranges as though the insects are being guided by an invisible conductor.

I've had letters from mathematicians, physicists, biochemists, neurophysiologists, epidemiologists, economists, sociologists; from people in marketing, information systems, civil engineering, and from a business enterprise that uses the concept of the small world for networking purposes on the Internet.Generally, their model demonstrated the truth in Mark Granovetter's observation that it is "the strength of weak ties"[16] that holds together a social network.

Although the specific model has since been generalized by Jon Kleinberg[citation needed], it remains a canonical case study in the field of complex networks.