Smilax

[1] They are climbing flowering plants, many of which are woody and/or thorny, in the monocotyledon family Smilacaceae, native throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Occasionally, the non-woody species such as the smooth herbaceous greenbrier (S. herbacea) are separated as genus Nemexia; they are commonly known by the rather ambiguous name carrion flowers.

[2] Though this myth has numerous forms, it always centers around the unfulfilled and tragic love of a mortal man who is turned into a flower, and a woodland nymph who is transformed into a brambly vine.

If pollination occurs, the plant will produce a bright red to blue-black spherical berry fruit about 5–10 mm in diameter that matures in the fall (autumn).

The genus has traditionally been considered as divided into a number of sections, but molecular phylogenetic studies reveals that these morphologically defined subdivisions are not monophyletic.

Since many Smilax colonies are single clones that have spread by rhizomes, both sexes may not be present at a site, in which case no fruit is formed.

This, coupled with the fact that birds and other small animals spread the seeds over large areas, makes the plants very hard to get rid of.

Deer and other herbivorous mammals will eat the foliage, as will some invertebrates such as Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), which also often drink nectar from the flowers.

Köhler's Medicinal Plants of 1887 discusses the American sarsaparilla (S. aristolochiifolia), but as early as about 1569, in his treatise devoted to syphilis, the Persian scholar Imad al-Din Mahmud ibn Mas‘ud Shirazi gave a detailed evaluation of the medical properties of chinaroot.

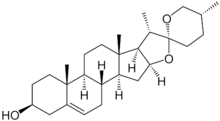

[13] Other active compounds reported from various greenbrier species are parillin (also sarsaparillin or smilacin), sarsapic acid, sarsapogenin and sarsaponin.

In 18th-century England, a type of beer called china-ale was made by infusing china-root (S. glabra) and coriander seeds in ale.