Smoke

Smoke is a suspension[3] of airborne particulates and gases[4] emitted when a material undergoes combustion or pyrolysis, together with the quantity of air that is entrained or otherwise mixed into the mass.

The smoke kills by a combination of thermal damage, poisoning and pulmonary irritation caused by carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide and other combustion products.

Smoke is an aerosol (or mist) of solid particles and liquid droplets that are close to the ideal range of sizes for Mie scattering of visible light.

[8] Fires burning with lack of oxygen produce a significantly wider palette of compounds, many of them toxic.

Phosphorus and antimony oxides and their reaction products can be formed from some fire retardant additives, increasing smoke toxicity and corrosivity.

[10] Pyrolysis of fluoropolymers, e.g. teflon, in presence of oxygen yields carbonyl fluoride (which hydrolyzes readily to HF and CO2); other compounds may be formed as well, e.g. carbon tetrafluoride, hexafluoropropylene, and highly toxic perfluoroisobutene (PFIB).

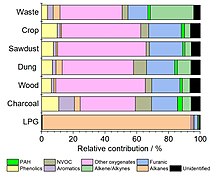

[11] Pyrolysis of burning material, especially incomplete combustion or smoldering without adequate oxygen supply, also results in production of a large amount of hydrocarbons, both aliphatic (methane, ethane, ethylene, acetylene) and aromatic (benzene and its derivates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; e.g. benzo[a]pyrene, studied as a carcinogen, or retene), terpenes.

[12] It also results in the emission of a range of smaller oxygenated volatile organic compounds (methanol, acetic acid, hydroxy acetone, methyl acetate and ethyl formate) which are formed as combustion by products as well as less volatile oxygenated organic species such as phenolics, furans and furanones.

[14] Combustion of solid fuels can result in the emission of many hundreds to thousands of lower volatility organic compounds in the aerosol phase.

[15] Presence of such smoke, soot, and/or brown oily deposits during a fire indicates a possible hazardous situation, as the atmosphere may be saturated with combustible pyrolysis products with concentration above the upper flammability limit, and sudden inrush of air can cause flashover or backdraft.

[citation needed] The visible particulate matter in such smokes is most commonly composed of carbon (soot).

Magnetic particles, spherules of magnetite-like ferrous ferric oxide, are present in coal smoke; their increase in deposits after 1860 marks the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Those undergo rapid dry precipitation, and the smoke damage in more distant areas outside of the room where the fire occurs is therefore primarily mediated by the smaller particles.

[20] Aerosol of particles beyond visible size is an early indicator of materials in a preignition stage of a fire.

Coal combustion produces emissions containing aluminium, arsenic, chromium, cobalt, copper, iron, mercury, selenium, and uranium.

These attack the passivation layers on metals and cause high temperature corrosion, which is a concern especially for internal combustion engines.

Markers for vehicle exhaust include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, hopanes, steranes, and specific nitroarenes (e.g. 1-nitropyrene).

Deposited hot particles of radioactive fallout and bioaccumulated radioisotopes can be reintroduced into the atmosphere by wildfires and forest fires; this is a concern in e.g. the Zone of alienation containing contaminants from the Chernobyl disaster.

Ionization chamber type smoke detectors detect particles of combustion that are invisible to the naked eye.

This explains why they may frequently false alarm from the fumes emitted from the red-hot heating elements of a toaster, before the presence of visible smoke, yet they may fail to activate in the early, low-heat smoldering stage of a fire.

In addition to the physical damage caused by the smoke of a fire – which manifests itself in the form of stains – is the often even harder to eliminate problem of a smoky odor.

A cloud of smoke, in contact with atmospheric oxygen, therefore has the potential of being ignited – either by another open flame in the area, or by its own temperature.

One day of exposure to PM2.5 at a concentration of 880 μg/m3, such as occurs in Beijing, China, is the equivalent of smoking one or two cigarettes in terms of particulate inhalation by weight.

[39][40] In some towns and cities in New South Wales, wood smoke may be responsible for 60% of fine particle air pollution in the winter.

[41] A year-long sampling campaign in Athens, Greece found a third (31%) of PAH urban air pollution to be caused by wood-burning, roughly as much as that of diesel and oil (33%) and gasoline (29%).

The largest exposure events are periods during the winter with reduced atmospheric dispersion to dilute the accumulated pollution, in particular due to the low wind speeds.

A smoke sample is drawn through a tube where it is diluted with air, the resulting smoke/air mixture is then pulled through a filter and weighed.

This method can over-read by capturing harmless condensates, or under-read due to the insulating effect of the smoke.

Highly dependent on light conditions and the skill of the observer it allocates a grayness number from 0 (white) to 5 (black) which has only a passing relationship to the actual quantity of smoke.

More importantly, generating smoke reduces the particle size to a microscopic scale thereby increasing the absorption of its active chemical principles.