Social history of post-war Britain (1945–1979)

The Labour Party, led by wartime Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee, won the 1945 post-war general election in an unexpected landslide and formed their first ever majority government.

[5] Historian Henry Pelling, noting that polls showed a steady Labour lead after 1942, points to the usual swing against the party in power; the Conservative loss of initiative; wide fears of a return to the high unemployment of the 1930s; the theme that socialist planning would be more efficient in operating the economy; and the mistaken belief that Churchill would continue as prime minister regardless of the result.

[12] Rebuilding necessitated fiscal austerity in order to maximise export earnings, while Britain's colonies and other client states were required to keep their reserves in pounds as "sterling balances".

[24] The most important Labour initiatives were the expansion of the welfare state, the founding of the National Health Service and nationalisation of the coal, gas, electricity, railways and other primary industries.

Hard line British Marxists were fervent believers in dialectical materialism and in fighting against capitalism and for workers' control, trade unionism, nationalisation of industry and centralised planning.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced prescription charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, leading Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (President of the Board of Trade) to resign.

[48] David Kynaston argues that the Labour Party under Attlee was led by conservative parliamentarians who always worked through constitutional parliamentary channels; they saw no need for large demonstrations, boycotts or symbolic strikes.

NATO was primarily aimed as a defensive measure against Soviet expansion, while helping bring its members closer together and enabled them to modernise their forces along parallel lines, also encouraging arms purchases from Britain.

[54] Bevin began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1948.

A handful of top elected officials made the decision in secret, ignoring the rest of the cabinet, in order to forestall the Labour Party's pacifist and anti-nuclear wing.

With relatively low unemployment during this period, the standard of living continued to rise, with new private and council housing developments increasing and the number of slum properties diminishing.

[73]Labour historian Martin Pugh stated: Keynesian economic management enabled British workers to enjoy a golden age of full employment which, combined with a more relaxed attitude towards working mothers, led to the spread of the two-income family.

[78] In comparing economic prosperity (using gross national product per person), the British record was one of steady downward slippage from seventh place in 1950, to twelfth in 1965, to twentieth in 1975.

British leaders feared their withdrawal would lead to a "doomsday scenario", with widespread communal strife, followed by the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of refugees.

By the 1990s, the failure of the IRA campaign to win mass public support or achieve its aim of a British withdrawal led to negotiations that in 1998 produced what is commonly referred to as the 'Good Friday Agreement'.

Peter Forster found that in answering pollsters, the British people reported an overwhelming belief in the truth of Christianity, a high respect for it, and a strong association between it and moral behaviour.

[89] Peter Hennessy argued that long-held attitudes did not stop change; by mid-century "Britain was still a Christian country only in a vague attitudinal sense, belief generally being more a residual husk than the kernel of conviction.

"[90][page needed] Kenneth O. Morgan agreed, noting that "the Protestant churches, Anglican, and more especially non-conformist, all felt the pressure of falling numbers and of secular challenges....

Initially these organizations were formed to pressure local and national governments to pass policies that would protect mothers, through superior suburban infrastructure and more affordable homegoods.

"[106] Feminist writers of the early post-war period, such as Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to allow for the possibility that women should be able to combine home duties with outside employment.

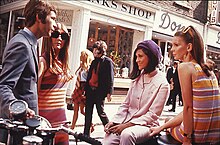

British groups and stars such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and many others gained huge followings in the UK and around the world, leading young people to question convention in everything from clothing to the class system.

[137] The new law was widely praised by the Conservatives because it honoured religion and social hierarchy, and by Labour because it opened new opportunities for the working-class, and also by the general public; because it ended the fees they previously had to pay.

Stephen Koss explains that the decline was caused by structural shifts: the major Fleet Street papers became properties of large, diversified capital empires with more interest in profits than politics.

[150] While film output peaked in 1936, the "golden age" of British cinema occurred in the 1940s, during which the directors David Lean, Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger, Carol Reed and Richard Attenborough produced their most highly acclaimed work.

Many post-war British actors achieved international fame and critical success, including: Maggie Smith, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Peter Sellers and Ben Kingsley.

In the decades after the Second World War immigration was greatest from the former British Empire, especially Ireland, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Caribbean, South Africa, Kenya and Hong Kong.

His speech foresaw "Rivers of Blood" and predicted that White "native" English citizens would be unable to access social services and be overwhelmed by foreign cultures.

[162] He argued that this was an aspect of British exceptionalism that primarily involved strategies of co-option and compromise in response to the growing political and cultural demands of young people.

Marwick argued that, in taking a more conciliatory approach, the UK establishment was able to stymie much of the rising social and political tension which convulsed some other liberal democracies in 1968.

[163] Loughran, Mycock, and Tonge later argued that reform of the electoral franchise in 1969 by lowering the voting age to 18 fits with Marwick's interpretation of establishment co-option strategy, among other explanations.