Soil mechanics

[6] Example applications are building and bridge foundations, retaining walls, dams, and buried pipeline systems.

The shear strength of soils is primarily derived from friction between the particles and interlocking, which are very sensitive to the effective stress.

[7][6] The article concludes with some examples of applications of the principles of soil mechanics such as slope stability, lateral earth pressure on retaining walls, and bearing capacity of foundations.

[3] Physical weathering includes temperature effects, freeze and thaw of water in cracks, rain, wind, impact and other mechanisms.

The most common mineral constituent of silt and sand is quartz, also called silica, which has the chemical name silicon dioxide.

Clay minerals typically have specific surface areas in the range of 10 to 1,000 square meters per gram of solid.

[3] Due to the large surface area available for chemical, electrostatic, and van der Waals interaction, the mechanical behavior of clay minerals is very sensitive to the amount of pore fluid available and the type and amount of dissolved ions in the pore fluid.

These elements along with calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, and carbon constitute over 99 per cent of the solid mass of soils.

Soil behavior, especially the hydraulic conductivity, tends to be dominated by the smaller particles, hence, the term "effective size", denoted by

[8] A stack of sieves with accurately dimensioned holes between a mesh of wires is used to separate the particles into size bins.

A known volume of dried soil, with clods broken down to individual particles, is put into the top of a stack of sieves arranged from coarse to fine.

The stack of sieves is shaken for a standard period of time so that the particles are sorted into size bins.

If there are a lot of fines (silt and clay) present in the soil it may be necessary to run water through the sieves to wash the coarse particles and clods through.

Stokes' law provides the theoretical basis to calculate the relationship between sedimentation velocity and particle size.

Clay particles can be sufficiently small that they never settle because they are kept in suspension by Brownian motion, in which case they may be classified as colloids.

Classification of the types of grains present in a soil does not[clarification needed] account for important effects of the structure or fabric of the soil, terms that describe compactness of the particles and patterns in the arrangement of particles in a load carrying framework as well as the pore size and pore fluid distributions.

The liquid limit is determined by measuring the water content for which a groove closes after 25 blows in a standard test.

[4][10] The plastic limit is the water content below which it is not possible to roll by hand the soil into 3 mm diameter cylinders.

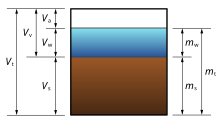

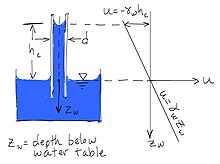

The thickness of the zone of capillary saturation depends on the pore size, but typically, the heights vary between a centimeter or so for coarse sand to tens of meters for a silt or clay.

Knowledge of the strength is necessary to determine if a slope will be stable, if a building or bridge might settle too far into the ground, and the limiting pressures on a retaining wall.

Different criteria can be used to define the "shear strength" and the "yield point" for a soil element from a stress–strain curve.

After a soil reaches the critical state, it is no longer contracting or dilating and the shear stress on the failure plane

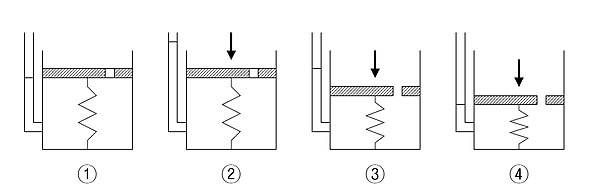

[3][4][11] Not recognizing the significance of dilatancy, Coulomb proposed that the shear strength of soil may be expressed as a combination of adhesion and friction components:[11] It is now known that the

[3][16] In addition to the friction and interlocking (dilatancy) components of strength, the structure and fabric also play a significant role in the soil behavior.

The structure and fabric include factors such as the spacing and arrangement of the solid particles or the amount and spatial distribution of pore water; in some cases cementitious material accumulates at particle-particle contacts.

The California Bearing Ratio (CBR) test is commonly used to determine the suitability of a soil as a subgrade for design and construction.

The field Plate Load Test is commonly used to predict the deformations and failure characteristics of the soil/subgrade and modulus of subgrade reaction (ks).

DSSM holds simply that soil deformation is a Poisson process in which particles move to their final position at random shear strains.

The steady-state was formally defined[21] by Steve J. Poulos Archived 2020-10-17 at the Wayback Machine an associate professor at the Soil Mechanics Department of Harvard University, who built off a hypothesis that Arthur Casagrande was formulating towards the end of his career.

Additionally DSSM explains key relationships in soil mechanics that to date have simply been taken for granted, for example, why normalized undrained peak shear strengths vary with the log of the overconsolidation ratio and why stress–strain curves normalize with the initial effective confining stress; and why in one-dimensional consolidation the void ratio must vary with the log of the effective vertical stress, why the end-of-primary curve is unique for static load increments, and why the ratio of the creep value Cα to the compression index Cc must be approximately constant for a wide range of soils.