Solar gain

Though transparent building materials such as glass allow visible light to pass through almost unimpeded, once that light is converted to long-wave infrared radiation by materials indoors, it is unable to escape back through the window since glass is opaque to those longer wavelengths.

Because of this, the most common metrics for quantifying solar gain are used as a standard way of reporting the thermal properties of window assemblies.

In the United States, The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE),[2] and The National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC)[3] maintain standards for the calculation and measurement of these values.

The shading coefficient (SC) is a measure of the radiative thermal performance of a glass unit (panel or window) in a building.

ASHRAE's table of solar heat gain factors[2] provides the expected solar heat gain for 1⁄8 in (3.2 mm) clear float glass at different latitudes, orientations, and times, which can be multiplied by the shading coefficient to correct for differences in radiation properties.

The lower the rating, the less solar heat is transmitted through the glass, and the greater its shading ability.

In addition to glass properties, shading devices integrated into the window assembly are also included in the SC calculation.

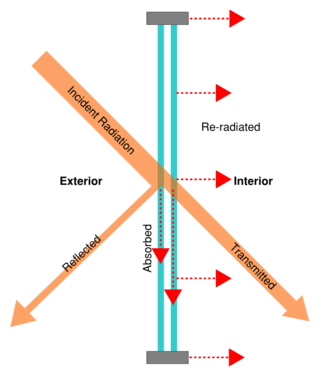

[5] Window design methods have moved away from the Shading Coefficient and towards the Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC), which is defined as the fraction of incident solar radiation that actually enters a building through the entire window assembly as heat gain (not just the glass portion).

Industry technical experts recognized the limitations of SC and pushed towards SHGC in the United States (and the analogous g-value in Europe) before the early 1990s.

[8] A conversion from SC to SHGC is not necessarily straightforward, as they each take into account different heat transfer mechanisms and paths (window assembly vs. glass-only).

It is important to note that the standard SHGC is calculated only for an angle of incidence normal to the window.

However this tends to provide a good estimate over a wide range of angles, up to 30 degrees from normal in most cases.

[3] SHGC can either be estimated through simulation models or measured by recording the total heat flow through a window with a calorimeter chamber.

In these components heat transfer is entirely due to absorptance, conduction, and re-radiation since all transmittance is blocked in opaque materials.

[11] Materials with high SRI will reflect and emit a majority of heat energy, keeping them cooler than other exterior finishes.

In the context of passive solar building design, the aim of the designer is normally to maximize solar gain within the building in the winter (to reduce space heating demand), and to control it in summer (to minimize cooling requirements).

Uncontrolled solar gain is undesirable in hot climates due to its potential for overheating a space.

To minimize this and reduce cooling loads, several technologies exist for solar gain reduction.

Low-emissivity coating is another more recently developed option that offers greater specificity in the wavelengths reflected and re-emitted.

Different types of glass can be used to increase or to decrease solar heat gain through fenestration, but can also be more finely tuned by the proper orientation of windows and by the addition of shading devices such as overhangs, louvers, fins, porches, and other architectural shading elements.

When placed in the path of admitted sunlight, high thermal mass features such as concrete slabs or trombe walls store large amounts of solar radiation during the day and release it slowly into the space throughout the night.

Some of the current research into this subject area is addressing the tradeoff between opaque thermal mass for storage and transparent glazing for collection through the use of transparent phase change materials that both admit light and store energy without the need for excessive weight.