Line (geometry)

In geometry, a straight line, usually abbreviated line, is an infinitely long object with no width, depth, or curvature, an idealization of such physical objects as a straightedge, a taut string, or a ray of light.

Euclid's Elements defines a straight line as a "breadthless length" that "lies evenly with respect to the points on itself", and introduced several postulates as basic unprovable properties on which the rest of geometry was established.

Euclidean line and Euclidean geometry are terms introduced to avoid confusion with generalizations introduced since the end of the 19th century, such as non-Euclidean, projective, and affine geometry.

In modern geometry, a line is usually either taken as a primitive notion with properties given by axioms,[1]: 95 or else defined as a set of points obeying a linear relationship, for instance when real numbers are taken to be primitive and geometry is established analytically in terms of numerical coordinates.

In an axiomatic formulation of Euclidean geometry, such as that of Hilbert (modern mathematicians added to Euclid's original axioms to fill perceived logical gaps),[1]: 108 a line is stated to have certain properties that relate it to other lines and points.

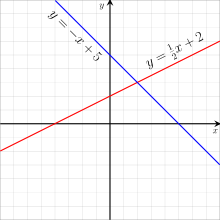

[1]: 300 In two dimensions (i.e., the Euclidean plane), two lines that do not intersect are called parallel.

In higher dimensions, two lines that do not intersect are parallel if they are contained in a plane, or skew if they are not.

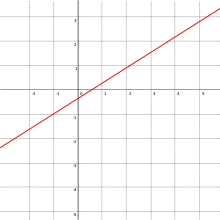

On a Euclidean plane, a line can be represented as a boundary between two regions.

More generally, in n-dimensional space n−1 first-degree equations in the n coordinate variables define a line under suitable conditions.

In affine coordinates, in n-dimensional space the points X = (x1, x2, ..., xn), Y = (y1, y2, ..., yn), and Z = (z1, z2, ..., zn) are collinear if the matrix

However, lines may play special roles with respect to other geometric objects and can be classified according to that relationship.

[9] However, the axiomatic definition of a line does not explain the relevance of the concept and is often too abstract for beginners.

So, the definition is often replaced or completed by a mental image or intuitive description that allows understanding what is a line.

The "definition" of line in Euclid's Elements falls into this category;[1]: 95 and is never used in proofs of theorems.

Lines in a Cartesian plane or, more generally, in affine coordinates, are characterized by linear equations.

(including vertical lines) is the set of all points whose coordinates (x, y) satisfy a linear equation; that is,

There are many variant ways to write the equation of a line which can all be converted from one to another by algebraic manipulation.

As a note, lines in three dimensions may also be described as the simultaneous solutions of two linear equations

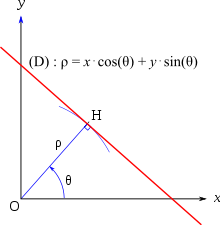

These equations can also be proven geometrically by applying right triangle definitions of sine and cosine to the right triangle that has a point of the line and the origin as vertices, and the line and its perpendicular through the origin as sides.

The previous forms do not apply for a line passing through the origin, but a simpler formula can be written: the polar coordinates

When a geometry is described by a set of axioms, the notion of a line is usually left undefined (a so-called primitive object).

Thus in differential geometry, a line may be interpreted as a geodesic (shortest path between points), while in some projective geometries, a line is a 2-dimensional vector space (all linear combinations of two independent vectors).

This flexibility also extends beyond mathematics and, for example, permits physicists to think of the path of a light ray as being a line.

[1]: 108 In the spherical representation of elliptic geometry, lines are represented by great circles of a sphere with diametrically opposite points identified.

In a different model of elliptic geometry, lines are represented by Euclidean planes passing through the origin.

The "shortness" and "straightness" of a line, interpreted as the property that the distance along the line between any two of its points is minimized (see triangle inequality), can be generalized and leads to the concept of geodesics in metric spaces.

It is also known as half-line (sometimes, a half-axis if it plays a distinct role, e.g., as part of a coordinate axis).

However, in order to use this concept of a ray in proofs a more precise definition is required.

In Euclidean geometry two rays with a common endpoint form an angle.

[14] The definition of a ray depends upon the notion of betweenness for points on a line.