Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, c. 1807–1808; died c. 1864) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir Twelve Years a Slave.

He was shipped to New Orleans, purchased by a planter, and held as a slave for 12 years in the Red River region of Louisiana, mostly in Avoyelles Parish.

His family and friends enlisted the aid of the Governor of New York, Washington Hunt, and Northup regained his freedom on January 3, 1853.

[1] The slave trader in Washington, D.C., James H. Birch, was arrested and tried, but acquitted because District of Columbia law at the time prohibited Northup as a black man from testifying against white people.

He lectured on behalf of the abolitionist movement, giving more than two dozen speeches throughout the Northeast about his experiences, to build momentum against slavery.

He largely disappeared from the historical record after 1857, although a letter later reported him alive in early 1863;[2] some commentators thought he had been kidnapped again, but historians believe it unlikely, as he would have been considered too old to bring a good price.

From Minerva, they moved to the farm of Clark Northup near Slyborough (Slyboro) in Granville, Washington County for several years.

[9][e] The family of four then lived at Alden Farm, a short distance north of Sandy Hill (now called Hudson Falls).

[31] When court was in session at the county seat of Fort Edward, she worked at Sherrill's Coffee House in Sandy Hill.

[32] After Northup was kidnapped, Anne and her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, went to work as domestic servants in New York City at Madame Jumel's Mansion on the East River in the summer of 1841.

A letter was prepared to the Governor of New York, Washington Hunt, based upon a deposition given by Anne Northup to Justice of the Peace Charles Hughes on November 19, 1852.

[35] While Northup gave talks about his book around the country, Anne worked in Bolton Landing on Lake George at the hotel Mohican House.

[36] After selling their land in Glens Falls, Anne Northup moved to the household of her daughter and son-in-law, Margaret and Philip Stanton, in Moreau, Saratoga County, where she again was recorded as married.

[13][46] The couple had become prosperous due to the income Anne received as a cook and that Northup made farming and playing the violin.

Over the seven years that the Northups lived in Saratoga Springs, they had made ends meet and dressed their children in fine clothes, but they had been unable to prosper as hoped.

[52] In March 1841, Anne went 20 miles to Sandy Hill, where she ran the kitchen at Sherrill's Coffee House during the court session.

[54] When they reached New York City, the men persuaded Northup to continue with them for a gig with their circus in Washington, D.C., offering him a generous wage and the cost of his return trip home.

[55] At this time, 20 years before the Civil War, the expansion of cotton cultivation in the Deep South had led to a continuing high demand for healthy slaves.

[13][27] However, Northup stated in his account of the ordeal in Twelve Years a Slave in Chapter II, "[w]hether they were accessory to my misfortunes – subtle and inhuman monsters in the shape of men – designedly luring me away from home and family, and liberty, for the sake of gold – those who read these pages will have the same means of determining as myself."

[56] At the New Orleans slave market, Birch's partner Theophilus Freeman sold Northup (who had been renamed Platt) along with two other individuals, Harry and Eliza (renamed Dradey)[65] to William Prince Ford, a preacher who engaged in small farming on Bayou Boeuf of the Red River in northern Louisiana.

His policy was to whip slaves if they did not meet daily work quotas he set for pounds of cotton to be picked, among other goals.

Henry B. Northup contacted New York Governor Washington Hunt, who took up the case, appointing the attorney general as his legal agent.

Once Northup's family was notified, his rescuers still had to do detective work to find the enslaved man, as he had partially tried to hide his location for protection in case the letters fell into the wrong hands, and Bass had not used his real name.

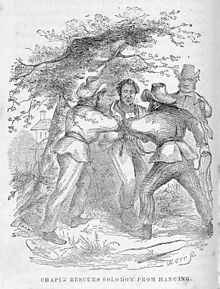

"[13][79] Attorney Henry B. Northup convinced Epps that it would be futile to contest the free papers in a court of law, so the planter conceded the case.

[27][80] After he made it back to New York, Solomon Northup wrote and published his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave (1853).

Northup was literate and provided the facts without hyperbole in "plain and candid language", while Wilson corrected style, grammar, and inconsistencies.

However, the sensational case immediately attracted national attention, and The New York Times published an article about the trial on January 20, 1853, just days after its conclusion and only two weeks after Northup's rescue.

[5][14][84] In the summer of 1857, he traveled to Canada to deliver a series of lectures; however, in Streetsville, Ontario, a hostile crowd prevented him from speaking.

Northup was assisted in the writing by David Wilson, a white man, and, according to Worley, some believed he would have biased the material.

His description of the "Yellow House" (also known as "The Williams Slave Pen"), in view of the Capitol, has helped researchers document the history of slavery in the District of Columbia.