Sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the reception of such waves and their perception by the brain.

In air at atmospheric pressure, these represent sound waves with wavelengths of 17 meters (56 ft) to 1.7 centimeters (0.67 in).

Acoustics is the interdisciplinary science that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gasses, liquids, and solids including vibration, sound, ultrasound, and infrasound.

[3] An audio engineer, on the other hand, is concerned with the recording, manipulation, mixing, and reproduction of sound.

At a fixed distance from the source, the pressure, velocity, and displacement of the medium vary in time.

[5] The mechanical vibrations that can be interpreted as sound can travel through all forms of matter: gases, liquids, solids, and plasmas.

[6][7] Studies has shown that sound waves are able to carry a tiny amount of mass and is surrounded by a weak gravitational field.

In air at standard temperature and pressure, the corresponding wavelengths of sound waves range from 17 m (56 ft) to 17 mm (0.67 in).

[13] The speed of sound depends on the medium the waves pass through, and is a fundamental property of the material.

The first significant effort towards measurement of the speed of sound was made by Isaac Newton.

He believed the speed of sound in a particular substance was equal to the square root of the pressure acting on it divided by its density: This was later proven wrong and the French mathematician Laplace corrected the formula by deducing that the phenomenon of sound travelling is not isothermal, as believed by Newton, but adiabatic.

Thus, the speed of sound is proportional to the square root of the ratio of the bulk modulus of the medium to its density.

In 20 °C (68 °F) air at sea level, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s (1,230 km/h; 767 mph) using the formula v [m/s] = 331 + 0.6 T [°C].

"[17] This means that the correct response to the question: "if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?"

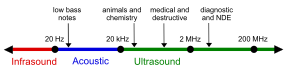

The physical reception of sound in any hearing organism is limited to a range of frequencies.

[18]: 249 Sometimes sound refers to only those vibrations with frequencies that are within the hearing range for humans[19] or sometimes it relates to a particular animal.

As a signal perceived by one of the major senses, sound is used by many species for detecting danger, navigation, predation, and communication.

Earth's atmosphere, water, and virtually any physical phenomenon, such as fire, rain, wind, surf, or earthquake, produces (and is characterized by) its unique sounds.

Many species, such as frogs, birds, marine and terrestrial mammals, have also developed special organs to produce sound.

Furthermore, humans have developed culture and technology (such as music, telephone and radio) that allows them to generate, record, transmit, and broadcast sound.

In science and engineering, noise is an undesirable component that obscures a wanted signal.

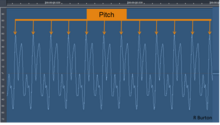

Selection of a particular pitch is determined by pre-conscious examination of vibrations, including their frequencies and the balance between them.

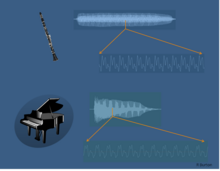

Timbre is perceived as the quality of different sounds (e.g. the thud of a fallen rock, the whir of a drill, the tone of a musical instrument or the quality of a voice) and represents the pre-conscious allocation of a sonic identity to a sound (e.g. "it's an oboe!").

This identity is based on information gained from frequency transients, noisiness, unsteadiness, perceived pitch and the spread and intensity of overtones in the sound over an extended time frame.

Even though a small section of the wave form from each instrument looks very similar, differences in changes over time between the clarinet and the piano are evident in both loudness and harmonic content.

Less noticeable are the different noises heard, such as air hisses for the clarinet and hammer strikes for the piano.

[31][32] The word texture, in this context, relates to the cognitive separation of auditory objects.

[33][34] In a thick texture, it is possible to identify multiple sound sources using a combination of spatial location and timbre identification.

Ultrasound is not different from audible sound in its physical properties, but cannot be heard by humans.