Harmonic

The term is employed in various disciplines, including music, physics, acoustics, electronic power transmission, radio technology, and other fields.

If the player gently touches one of these positions, then these other characteristic modes will be suppressed.

); this allows the harmonic to sound, a pitch which is always higher than the fundamental frequency of the string.

A whizzing, whistling tonal character, distinguishes all the harmonics both natural and artificial from the firmly stopped intervals; therefore their application in connection with the latter must always be carefully considered.

[citation needed] Most acoustic instruments emit complex tones containing many individual partials (component simple tones or sinusoidal waves), but the untrained human ear typically does not perceive those partials as separate phenomena.

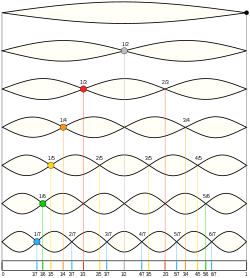

Oscillators that produce harmonic partials behave somewhat like one-dimensional resonators, and are often long and thin, such as a guitar string or a column of air open at both ends (as with the metallic modern orchestral transverse flute).

Wind instruments whose air column is open at only one end, such as trumpets and clarinets, also produce partials resembling harmonics.

In practical use, no real acoustic instrument behaves as perfectly as the simplified physical models predict; for example, instruments made of non-linearly elastic wood, instead of metal, or strung with gut instead of brass or steel strings, tend to have not-quite-integer partials.

Some acoustic instruments emit a mix of harmonic and inharmonic partials but still produce an effect on the ear of having a definite fundamental pitch, such as pianos, strings plucked pizzicato, vibraphones, marimbas, and certain pure-sounding bells or chimes.

Antique singing bowls are known for producing multiple harmonic partials or multiphonics.

Building on of Sethares (2004),[5] dynamic tonality introduces the notion of pseudo-harmonic partials, in which the frequency of each partial is aligned to match the pitch of a corresponding note in a pseudo-just tuning, thereby maximizing the consonance of that pseudo-harmonic timbre with notes of that pseudo-just tuning.

The relative strengths and frequency relationships of the component partials determine the timbre of an instrument.

This is part of the normal method of obtaining higher notes in wind instruments, where it is called overblowing.

For example, lightly fingering the node found halfway down the highest string of a cello produces the same pitch as lightly fingering the node 1 / 3 of the way down the second highest string.

While it is true that electronically produced periodic tones (e.g. square waves or other non-sinusoidal waves) have "harmonics" that are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, practical instruments do not all have this characteristic.

(2) The production of harmonics by the slight pressure of the finger on the open string is more useful.

When produced by pressing slightly on the various nodes of the open strings they are called 'natural harmonics'.

[12] Occasionally a score will call for an artificial harmonic, produced by playing an overtone on an already stopped string.

As a performance technique, it is accomplished by using two fingers on the fingerboard, the first to shorten the string to the desired fundamental, with the second touching the node corresponding to the appropriate harmonic.

Composer Arnold Dreyblatt is able to bring out different harmonics on the single string of his modified double bass by slightly altering his unique bowing technique halfway between hitting and bowing the strings.

Composer Lawrence Ball uses harmonics to generate music electronically.