Depth sounding

Data taken from soundings are used in bathymetry to make maps of the floor of a body of water, such as the seabed topography.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the agency responsible for bathymetric data in the United States, still uses fathoms and feet on nautical charts.

The term lives on in today's world in echo sounding, the technique of using sonar to measure depth.

It continues in widespread use today in recreational boating and as an alternative to electronic echo sounding devices.

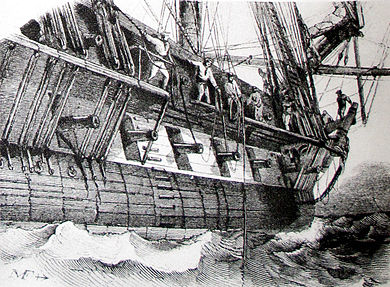

Sounding by lead and line continued throughout the medieval and early modern periods and is still commonly used today.

These marks are made of leather, calico, serge and other materials, and so shaped and attached that it is possible to "read" them by eye during the day or by feel at night.

The tallow would bring up part of the bottom sediment (sand, pebbles, clay, shells) and allow the ship's officers to better estimate their position by providing information useful for pilotage and anchoring.

The introduction of new machines was understood as a way to introduce standardised practices for sounding in a period in which naval discipline was of great concern.

It consisted of an inflatable canvas bag (the buoy) and a spring-loaded wooden pulley block (the nipper).

The spring-loaded pulley would then catch the rope when the lead hit the sea bed, ensuring an accurate reading of the depth.

With the growth of seabed telegraphy in the later nineteenth century, new machines were introduced to measure much greater depths of water.

In this case, the line consisted of a drum of piano wire whilst the lead was of a much greater weight.

Later versions of Kelvin's machine also featured a motorised drum in order to facilitate the winding and unwinding of the line.