Southern American English

[8][9][10] A diversity of earlier Southern dialects once existed: a consequence of the mix of English speakers from the British Isles (including largely English and Scots-Irish immigrants) who migrated to the American South in the 17th and 18th centuries, with particular 19th-century elements also borrowed from the London upper class and enslaved African-Americans.

Following the American Civil War, as the South's economy and migration patterns fundamentally transformed, so did Southern dialect trends.

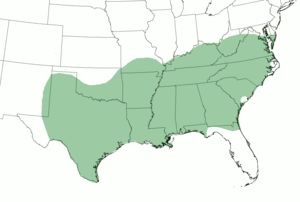

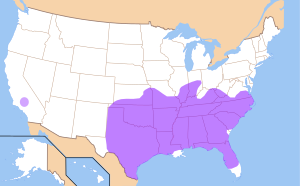

[11] The main result, further intensified by later upheavals such as the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and perhaps World War II, is that a newer and more unified form of Southern American English consolidated, beginning around the last quarter of the 19th century, radiating outward from Texas and Appalachia through all the traditional Southern States until around World War II.

Despite the slow decline of the modern Southern accent,[16] it is still documented as widespread as of the 2006 Atlas of North American English.

The Atlas notably identifies several culturally Southern cities in particular as lacking a Southern accent, either having shifted away from it or having never had it to begin with, such as Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia; Raleigh and Greenville, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; Atlanta and possibly Savannah, Georgia; Abilene, El Paso, Austin, and possibly Corpus Christi, Texas; and Oklahoma City.

The South as a present-day dialect region generally includes all of the pronunciation features below, which are popularly recognized in the United States as making up a "Southern accent".

However, there is still variation in Southern speech regarding potential differences based on factors like a speaker's exact sub-region, age, ethnicity, etc.

[51] The accents of Texas are diverse, for example with important Spanish influences on its vocabulary;[52] however, much of the state is still an unambiguous region of modern rhotic Southern speech, strongest in the cities of Dallas, Lubbock, Odessa, and San Antonio,[4] which all firmly demonstrate the first stage of the Southern Shift, if not also further stages of the shift.

[53] Texan cities that are noticeably "non-Southern" dialectally are Abilene and Austin; only marginally Southern are Houston, El Paso, and Corpus Christi.

Since the early 1900s, Cajuns additionally began to develop their vernacular dialect of English, which retains some influences and words from French, such as "cher" (dear) or "nonc" (uncle).

This dialect fell out of fashion after World War II but experienced a renewal among primarily male speakers born since the 1970s, who have been the most attracted by, and the biggest attractors of, a successful Cajun cultural renaissance.

[56] A separate historical English dialect from the above Cajun one, spoken only by those raised in the Greater New Orleans area, is traditionally non-rhotic and noticeably shares more pronunciation commonalities with a New York accent than with other Southern accents, due to commercial ties and cultural migration between the two cities.

The 2006 Atlas of North American English identifies Atlanta, Georgia, as a dialectal "island of non-Southern speech",[60] Charleston, South Carolina, likewise as "not markedly Southern in character", and the traditional local accent of Savannah, Georgia, as "giving way to regional [Midland] patterns",[61] despite these being three prominent Southern cities.

[66] Before becoming a phonologically unified dialect region, the South was once home to an array of much more diverse accents at the local level.

Features of the deeper interior Appalachian South largely became the basis for the newer Southern regional dialect; thus, older Southern American English primarily refers to the English spoken outside of Appalachia: the coastal and former plantation areas of the South, best documented before the Civil War, on the decline during the early 1900s, and non-existent in speakers born since the civil rights movement.

Atwood (1953) for example, finds that educated people try to avoid multiple modals, whereas Montgomery (1998) suggests the opposite.

It serves to soften obligations or suggestions, make criticisms less personal, and to overall express politeness, respect, or courtesy.

Soon, racial segregation laws followed by decades of cultural, sociological, economic, and technological changes such as WWII and the increasing prevalence of mass media further complicated the relationship between AAVE and all other English dialects.

It is uncertain to what extent current white Southern English borrowed elements from early AAVE, and vice versa.

[67] Another possible influence on the divergence of AAVE and white Southern American English (i.e., the disappearance of older Southern American English) is that historical and contemporary civil rights struggles have over time caused the two racial groups "to stigmatize linguistic variables associated with the other group".

[67] This may explain some of the differences outlined above, including why most traditionally non-rhotic white Southern accents have shifted to become intensely rhotic.

[101] Meanwhile, Southerners themselves tend to have mixed judgments of their accent, some similarly negative but others positively associating it with a laid-back, plain, or humble attitude.

[101] The sum of negative associations nationwide, however, is the main presumable cause of a gradual decline of Southern accent features, since the middle of the 20th century onwards, particularly among younger and more urban residents of the South.