Soviet annexation of Eastern Galicia and Volhynia

On the basis of a secret clause of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939, capturing the eastern provinces of the Second Polish Republic.

On September 17, 1939 the Red Army entered Polish territory, acting on the basis of a secret clause of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

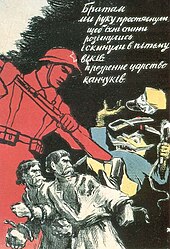

The Soviet Union would later deny the existence of this secret protocol, claiming that it was never allied with the German Reich, and acted independently to protect the Ukrainian and White Ruthenian (modern Belarusian) minorities in the disintegrating Polish state.

[7] Immediately after entering Poland's territory, the Soviet army helped to set up "provisional administrations" in the cities and "peasant committees" in the villages in order to organize one-list elections to the new "People's Assembly of Western Ukraine".

Based on these results, the People's Assembly of Western Ukraine, headed by Kyryl Studynsky (a prominent academic and figure in the Christian Social Movement), consisted of 1,484 deputies.

The assembly voted unanimously to thank Stalin for liberation and sent a delegation headed by Studynsky to Moscow to ask for formal inclusion of the territories into the Ukrainian SSR.

[10] The First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine Nikita Khrushchev asked the chief of the Special Department of the Ukrainian Front Anatoliy Mikheyev, a 28 year old major, "What kind of a job is it when no one is executed?

[10] The unlawful incidents became so big a problem that the 6th Army prosecutor Nechyporenko was forced to write a personal letter to Stalin asking to intervene and stop the atrocities.

The civilian administration in those regions annexed from Poland was organized by December 1939 and was drawn mostly from newcomers from eastern Ukraine and Russia; only 20% of government employees were from the local population.

The reason for this belief was that most of the previous Polish administrators were deported, and the local Ukrainian intelligentsia who could have taken their place were generally deemed to be too nationalistic for such work by the Soviets.

[3][4] Due to the sensitive location of western Ukraine along the border with German-held territory, the Soviet administration made attempts, initially, to gain the loyalty and respect of the Ukrainian population.

[3] The Soviet authorities then began taking land from the peasants themselves and turning it over to collective farms, which affected 13% of western Ukrainian farmland by 1941.

[4] At the time of the Soviet annexation of Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church had approximately 2,190 parishes, three theological seminaries, 29 monasteries, 120 convents and 3.5 million faithful.

A prominent Lviv priest and close confidante of Andrey Sheptytsky,[12] Havriil Kostelnyk, who had been the principal critic of the Vatican's Latinization policies and spokesperson for the "Easternizing" trend within the Ukrainian Catholic Church, was asked to organize a "National" Greek Catholic Church, with Soviet support, that would be independent of the Vatican and which would split the faithful in western Ukraine.

For example, in June 1940, the superior of the Studite convent in Lviv, Olena Viter, was imprisoned and tortured in order to "confess" that Sheptytsky was a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and that she was supplying him with weapons.

[14] In April 1940 the Soviet authorities in the annexed territories began to extend their repressive measures towards the general Ukrainian population.

Prior to retreating, the Soviet authorities, unwilling to evacuate prisoners, chose to kill all inmates whether or not they had committed major or minor crimes and whether or not they were held for political reasons.

[12] On June 30, 1941, Ukrainian nationalist commandos under German command captured Lviv which had been evacuated by Soviet forces and declared an independent state allied with Nazi Germany.

The Soviet annexation of some 51.6% of the territory of the Second Polish Republic,[20] where about 13,200,000 people lived in 1939 including Poles and Jews,[21] was an important event in the history of contemporary Ukraine and Belarus, because it brought within Ukrainian and Belarusian SSR new territories inhabited in part by ethnic Ukrainian and Belarusian people, and thus unified previously separated branches of these nations.

The postwar population transfers imposed by Joseph Stalin, and the mass killings of the Holocaust, solidified the mono-ethnic character of these lands by nearly a complete eradication of the Polish and Jewish presence there.

Ukraine and Belarus achieved independence in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union and became nation states delineated by borders of the 50-year-old republics.

[22] "The process of amalgamation", wrote Orest Subtelny, a Canadian historian of Ukrainian descent, "was not only a major aspect of the post-war period, but an event of epochal significance in the history of Ukraine.