Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina

The use of force had been made illegal by the Conventions for the Definition of Aggression in July 1933, but from an international legal standpoint, the new status of the annexed territories was eventually based on a formal agreement through which Romania consented to the retrocession of Bessarabia and cession of Northern Bukovina.

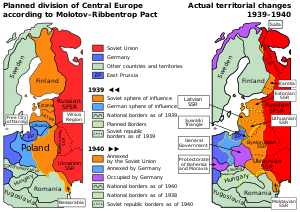

[2] On 24 June, Nazi Germany, which had acknowledged the Soviet interest in Bessarabia in a secret protocol to the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, had been made aware prior to the planned ultimatum but did not inform the Romanian authorities and was unwilling to provide support.

[13][14] The figures showed a strong decrease in the proportion of Moldovans and Romanians compared to the census of 1817, which had been conducted shortly after the Russian Empire annexed Bessarabia in 1812.

[21] To calm the situation, Entente representatives in Iași issued a guarantee that the presence of the Romanian Army was only a temporary military measure for the stabilisation of the front, without further affecting the political life of the region.

[39] Romanian sovereignty over Bessarabia was de jure recognized by the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Japan in the Bessarabian Treaty, signed on 28 October 1920.

[47] On 9 February 1929, the Soviet Union signed a protocol with its western neighbors, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, and Romania, confirming adherence to the terms of the Pact.

In January 1932 in Riga and in September 1932 in Geneva, Soviet-Romanian negotiations were held as a prelude to a non-aggression treaty, and on 9 June 1934, diplomatic relations were established between both countries.

Article III of its Secret Additional Protocol stated: With regard to Southeastern Europe attention is called by the Soviet side to its interest in Bessarabia.

From 14–17 June 1940, the Soviet Union gave ultimatum notes to Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia, and when the ultimata were satisfied, it used the bases that it had gained to occupy those territories.

[60] The German Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop, was informed by the Soviets of their intentions to send an ultimatum to Romania regarding Bessarabia and Bukovina on 24 June 1940.

Carol communicated his wish to stand against the Soviet Union and asked for their countries to influence Hungary and Bulgaria in the hopes of not declaring war against Romania and to reclaim Transylvania and Southern Dobruja.

[67] On 27 June, a second Soviet ultimatum note put forward a specific time frame that requested the evacuation of the Romanian government from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina within four days.

[67] On the morning of 28 June 1940, following advice by both Germany and Italy, the Romanian government, led by Gheorghe Tătărescu, under the semi-authoritarian rule of Carol II, agreed to submit to the Soviet demands.

The decision to accept the Soviet ultimatum and to start a "withdrawal" (avoiding the use of ceding) from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina was deliberated upon by the Romanian Crown Council during the night of 27-28 June.

The military installations and casemates, built during a 20-year period for the event of a Soviet attack, were relinquished without a fight, the Romanian Army being placed by its command under strict orders not to respond to provocations.

In a declaration to the local population, the Soviet command stated: "The great hour of your liberation from the yoke of Romanian boyars, landowners, capitalists and Siguranța has arrived".

[71][72] The situation was the same on the other side of the border: roughly 300 (or between 80 and 400, according to other sources[73]) civilians, most of them Jews, waiting to leave for Soviet-controlled Bessarabia were shot by the Romanian army in Galați railway station on 30 June 1940.

A collectivisation drive was also started in 1941, but the lack of agricultural machinery made the progress extremely slow, with 3.7% of the peasant households being included in a kolkhoz or a sovkhoz by the middle of year.

[78]The territorial concessions of 1940 produced deep sorrow and resentment among Romanians and hastened the decline in popularity of the regime led by King Carol II of Romania.

Overall, the desire to regain the lost territories was invoked as a justification by Romania for its entry into World War II on the side of the Axis against the Soviet Union.

Between late 1941 and early 1944, Romania occupied and administered the region between the Dniester and Southern Bug rivers, known as Transnistria, as well as sending expeditionary forces to support the German advance into the Soviet Union in several areas.

In the context of increasing antisemitism within the country during the late 1930s, the Antonescu government officially adopted a narrative of Jewish Bolshevism, declaring Jews responsible for Romania's territorial losses during the summer of 1940.

Thus, after the reconquest in July 1941, in a coordinated effort with Germany, the Romanian government embarked on a campaign to "cleanse" the recaptured territories, engaging in the mass deportation and murder of the remaining Jews in Bukovina and Bessarabia who hadn't fled further into the Soviet Union.

Romanian gendarmerie units, alongside German troops and local militias, also carried out the destruction of the Jewish community in Transnistria, murdering between 115,000 and 180,000 people.

From February until August 1944, Romania struggled to defend itself in the face of Soviet counteroffensives, with the Antonescu regime ultimately being liquidated upon the country's total occupation by the Red Army in late 1944.

Overall, the Romanian army suffered 475,070 casualties on the Eastern Front during World War II, with 245,388 either killed in action, missing, or otherwise dying in hospitals or in non-battle circumstances.

From August 1944 to May 1945, about 300,000 people were conscripted into the Soviet Army from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina and were sent to fight against Germany in Lithuania, East Prussia, Poland and Czechoslovakia.

[92][93] Based on postwar statistics, the historian Igor Cașu has shown that Moldovans and Romanians comprised roughly 50 percent of the deportees, with the rest being Jews, Russians, Ukrainians, Gagauzes, Bulgarians and Roma people.

[95] In early Soviet historiography, the chain of events that led to the creation of the Moldavian SSR was described as a "liberation of the Moldovan people from a 22-year-old occupation by boyar Romania."

The Stalinist aggression constituted a serious breach of the legal norms of behavior of states in international relations, of the obligations assumed under the Briand-Kellog Pact of 1928, and under the London Convention on the Definition of the Aggressor of 1933".