Ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Before the perestroika Soviet era reforms of Gorbachev that promoted a more liberal form of socialism, the formal ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Marxism–Leninism, a form of socialism consisting of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state that aimed to realize the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The Soviet Union's ideological commitment to achieving communism included the national communist development of socialism in one country and peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries while engaging in anti-imperialism to defend the international proletariat, combat the predominant prevailing global system of capitalism and promote the goals of Bolshevism.

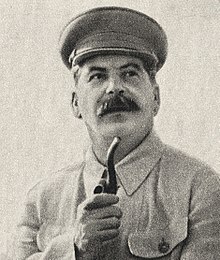

The state ideology of the Soviet Union—and thus Marxism–Leninism—derived and developed from the theories, policies, and political praxis of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin.

[1] The relationship between ideology and decision-making was at best ambivalent, with most policy decisions taken in the light of the continued, permanent development of Marxism–Leninism,[2] which, as the only truth, could not by its very nature become outdated.

[5] The state professed a belief in the feasibility of total communist mode of production, and all policies were seen as justifiable if it contributed to the Soviet Union's reaching that stage.

[7] Since Karl Marx barely, if ever wrote about how the socialist mode of production would look like or function, these tasks were left for later scholars like Lenin to solve.

[12] Stalin tried to explain the reasoning behind it at the 16th Congress (held in 1930);[12] We stand for the strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which represents the mightiest and most powerful authority of all forms of State that have ever existed.

Lenin, according to his interpretation of Marx's theory of the state, believed democracy to be unattainable anywhere in the world before the proletariat seized power.

[18] Marx, similar to Lenin, considered it fundamentally irrelevant whether a bourgeois state was ruled according to a republican, parliamentarian or constitutionally monarchic political system because this did not change the mode of production itself.

[22] Lenin had now concluded that the dictatorship of the proletariat would not alter the relationship of power between persons, but rather "transform their productive relations so that, in the long run, the realm of necessity could be overcome and, with that, genuine social freedom realised".

[23] It was in the period of 1920–1921 that Soviet leaders and ideologists began differentiating between socialism and communism; hitherto the two terms had been used to describe similar conditions.

[23] By now, the party leaders believed that universal mass participation and true democracy could only take form in the last stage, if only because of Russia's current conditions at the time.

In early Bolshevik discourse, the term "dictatorship of the proletariat" was of little significance; the few times it was mentioned, it was likened to the form of government which had existed in the Paris Commune.

[23] With the ensuing Russian Civil War and the social and material devastation that followed, however, its meaning was transformed from communal democracy to disciplined totalitarian rule.

[29] These oppressive measures led to another reinterpretation of the dictatorship of the proletariat and socialism in general; it was now defined as a purely economic system.

[30] Slogans and theoretical works about democratic mass participation and collective decision-making were now replaced with texts which supported authoritarian management.

[35] On the other hand, Karl Kautsky, from the SDP, held a highly dogmatic view, claiming that there was no crisis within Marxist theory.

In the post-Soviet era even many Ukrainians, Georgians, and Armenians feel that their countries were forcibly annexed by the Bolsheviks, but this has been a problematic view because the pro-Soviet factions in these societies were once sizable as well.

The loss by imperialism of its dominating role in world affairs and the utmost expansion of the sphere in which the laws of socialist foreign policy operate are a distinctive feature of the present stage of social development.

[40] The concept claimed that the two systems were developed "by way of diametrically opposed laws", which led to "opposite principles in foreign policy.

[38] Lenin believed that international politics were dominated by class struggle, and Stalin stressed in the 1940s the growing polarization which was occurring in the capitalist and socialist systems.

[38] Despite this, Soviet theorists still considered peaceful coexistence as a continuation of the class struggle between the capitalist and socialist worlds, just not one based on armed conflict.

[38] Also, with the establishment of socialist regimes in Eastern Europe and Asia, Soviet foreign policy-planners believed that capitalism had lost its dominance as an economic system.

[42] In it, Stalin stated, that he did not believe an inevitable conflict between the working class and the peasants would take place, further adding that "socialism in one country is completely possible and probable".

[42] Stalin held the view common amongst most Bolsheviks at the time; there was possibility of real success for socialism in the Soviet Union despite the country's backwardness and international isolation.

[42] While Grigoriy Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and Nikolai Bukharin, together with Stalin, opposed Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution, they diverged on how socialism could be built.

[42] According to Bukharin, Zinoviev and Kamenev supported the resolution of the 14th Conference (held in 1925) which stated that "we cannot complete the building of socialism due to our technological backwardness.

[44] In late 1925, Stalin received a letter from a party official which stated that his position of "Socialism in One Country" was in contradiction with Friedrich Engels own writings on the subject.

[44] Zinoviev on the other hand, disagreed with both Trotsky and Bukharin and Stalin, holding instead steadfast to Lenin's own position from 1917 to 1922, and continued to claim that only a defecting form of socialism could be constructed in the Soviet Union without a world revolution.

[45] Bukharin, by now, began arguing for the creation of an autarkic economic model, while Trotsky, in contrast, claimed that the Soviet Union had to participate in the international division of labour to develop.