Soviet offensive plans controversy

[1] Suvorov's main argument, that the Soviet government was planning to launch an offensive campaign against Nazi Germany, has been widely discredited as a historical distortion.

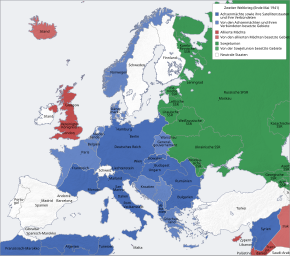

The debate began in the late 1980s when Viktor Suvorov published a journal article and later the book Icebreaker in which he claimed that Stalin had seen the outbreak of war in Western Europe as an opportunity to spread communist revolutions throughout the continent, and that the Soviet military was being deployed for an imminent attack at the time of the German invasion.

[4] Suvorov's thesis was fully or partially accepted by a limited number of historians, including Valeri Danilov, Joachim Hoffmann, Mikhail Meltyukhov, and Vladimir Nevezhin and attracted public attention in Germany, Israel, and Russia.

[9] British historian Evan Madsley wrote in his book "Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941–1945": "Stalin and the Soviet high command were aware of the scale of the German build-up, but they believed they had matched it and that the Red Army could deal with an invasion, if it came to that.

... Stalin’s key assumption was perhaps that German policy was undecided, but that rash Soviet action could bring about an unnecessary, or at least premature, war with the Reich.

"[10]Vladimir Rezun, a former officer of the Soviet military intelligence and a defector to the UK, justified the claim in his 1988 book Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War under the pseudonym Viktor Suvorov[11] and again in several subsequent books: M Day, The Last Republic, Cleansing, Suicide, The Shadow of Victory, I Take my words Back, The Last Republic II, The Chief Culprit, and Defeat.

[13] Suvorov offers as another piece of evidence the extensive effort Stalin took to conceal general mobilization by manipulating the laws setting the conscription age.

[3] According to an article in The Inquiries Journal by Christopher J. Kshyk, the debate on whether Stalin intended to launch offensive against Germany in 1941 remains inconclusive but has produced an abundance of scholarly literature and helped to expand the understanding of larger themes in Soviet and world history during the interwar period.

Kshyk also notes the problems because of the still-limited access to Soviet archives and the emotional nature of debate from national pride and the participants' political and personal motivations.

[23] American historian Sean McMeekin claims that while the Suvorov thesis was largely ignored in the West, based on the authority of notable critics like Glantz and Gorodetsky, it was nevertheless treated seriously in the Eastern European countries, which were directly involved in the German-Soviet struggle.

[27] However, Robin Edmonds argued that the Red Army's planning staff would not have been doing its job well if it had not considered the possibility of a preemptive strike against the Wehrmacht,[28] and Teddy J. Uldricks pointed out that no documentary evidence shows that Zhukov's proposal was ever accepted by Stalin.

[31] Colonel Dr. Pavel N. Bobylev[32] was one of the military historians from the Soviet (later Russian) Ministry of Defense who in 1993 published the materials of the January 1941 games on maps.

The action started only when the Soviets ("Easterners") attacked westward from their border and, in the second game ("South Variant"), even from positions deep inside the enemy's land.

[3] British historian Evan Mawdsley asserted that although Stalin was aware about large-scale German deployments across the Soviet borders, he made a fatal miscalculation due to his ignorance of Hitler's real motives in 1941.

Stalin thought that the German leadership was undecided and sought to avoid making moves that could potentially escalate into a war with Nazi Germany.

Although they received several intelligence reports of a forthcoming German invasion, Soviet leaders assumed that Hitler wanted to avoid a two-front war.

[37] Many other western scholars, such as Teddy J. Uldricks,[3] Derek Watson,[38] Hugh Ragsdale,[39] Roger Reese,[40] Stephen Blank,[41] and Robin Edmonds,[28] and Ingmar Oldberg[42] agree that the Suvorov's major weakness is "that the author does not reveal his sources" and rely on circumstantial evidence.

[7] Suvorov's most controversial thesis was that the Red Army had made extensive preparations for an offensive war in Europe but was totally unprepared for defensive operations on its own territory.

[46] Antony Beevor wrote that "the Red Army was simply not in a state to launch a major offensive in the summer of 1941, and in any case Hitler's decision to invade had been made considerably earlier.

Goebbels summed up the perception of the top Nazi leaders in a diary entry of early May 1941: ‘Stalin and his people remain completely inactive.

Like a rabbit confronted by a snake.’"[52] In a 1987 article in the Historische Zeitschrift journal, the German historian Klaus Hildebrand argued that both Hitler and Stalin had separately planned to attack each other in 1941.

Radzinsky cited a document preserved in the Military-Memorial Center of the Soviet General Staff, which was a draft of a plan for military strategy in case of war with Germany, drawn up by Georgy Zhukov, dated May 15, 1941, and signed by Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Nikolai Vatutin.

Both researchers came to the conclusion that Zhukov's plan of May 15, 1941 reflected Stalin's alleged speech of 19 August 1939 heralding the birth of the new offensive Red Army.

The differences between them were slight, all documents (including operational maps signed by the Deputy Chief of General Staff of the Red Army) are the plans for the invasion with depth offensive 300 km.

: "The new evidence shows that by encouraging Hitler to start World War II, Stalin hoped to simultaneously ignite a world-wide revolution and conquer all of Europe".