Spandau Prison

In the aftermath of the Reichstag fire of 1933, opponents of Hitler, and journalists such as Egon Kisch and Carl von Ossietzky, were held there in so-called protective custody.

While it was formally operated by the Prussian Ministry of Justice, the Gestapo tortured and abused its inmates, as Kisch recalled in his memories of the prison.

Spandau was one of only two Four-Power organisations to continue to operate after the breakdown of the Allied Control Council; the other was the Berlin Air Safety Centre.

All materials from the demolished prison were ground to powder and dispersed in the North Sea, or buried at the former RAF Gatow airbase,[3] with the exception of a single set of keys now exhibited in the regimental museum of the King's Own Scottish Borderers at Berwick Barracks.

Dönitz favoured growing beans, Funk tomatoes and Speer daisies, although the Soviet director subsequently banned flowers for a time.

On days without access to the garden, for instance when it was raining, the prisoners occupied their time making envelopes together in the main corridor.

The debate surrounding the imprisonment of seven war criminals in such a large space, with numerous and expensive complementary staff, was only heightened as time went on and prisoners were released.

Acrimony reached its peak after the release of Speer and Schirach in 1966, leaving only one inmate, Hess, remaining in an otherwise under-utilized prison.

The directors and guards of the Western powers (France, Britain, and the United States) repeatedly voiced opposition to many of the stricter measures and made near-constant protest about them to their superiors throughout the prison's existence, but they were invariably vetoed by the Soviet Union, which favored a tougher approach.

The Soviet Union, which suffered between 10 and 19 million civilian deaths[4] during the war and had pressed at the Nuremberg trials for the execution of all the current inmates, was unwilling to compromise with the Western powers in this regard, both because of the harsher punishment that they felt was justified, and to stress the Communist propaganda line that the capitalist powers had supposedly never been serious about denazification.

However, a more contemporary consideration was that the continued incarceration of even one Nazi (i.e. Hess) in Spandau ensured a conduit that guaranteed the Soviets access to West Berlin would remain open, and Western commentators frequently accused the Russians of keeping Spandau prison in operation chiefly as a centre for Soviet espionage operations.

This routine, except the time allowed in the garden, changed very little throughout the years, although each of the controlling nations made their own interpretation of the prison regulations.

These supplementary lines were free of the censorship placed on authorised communications, and were also virtually unlimited in volume, ordinarily occurring on either Sundays or Thursdays (except during times of total lock-down of exchanges).

Albert Speer, after having his official request to write his memoirs denied, finally began setting down his experiences and perspectives of his time with the Nazi regime, which were smuggled out and later released as a bestselling book, Inside the Third Reich.

[citation needed] Walther Funk managed to obtain a seemingly constant supply of cognac (all alcohol was banned) and other treats that he would share with other prisoners on special occasions.

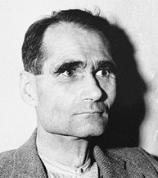

The prisoners, still subject to the petty personal rivalries and battles for prestige that characterized Nazi party politics, divided themselves into groups: Albert Speer and Rudolf Hess were the loners, generally disliked by the others – the former for his admission of guilt and repudiation of Hitler at the Nuremberg trials, the latter for his antisocial personality and perceived mental instability.

There is also a collection of medical reports concerning Baldur von Schirach, Albert Speer, and Rudolf Hess made during their confinement at Spandau, which have survived.

Despite preferring to stay together, the two of them continued their wartime feud and argued most of the time over whether Raeder's battleships or Dönitz's U-boats were responsible for losing the war.

A paranoid hypochondriac, he repeatedly complained of all forms of illness, mostly stomach pains, and was suspicious of all food given to him, always taking the dish placed farthest away from him as a means of avoiding being poisoned.

The fact that Hess repeatedly shirked duties the others had to bear and received other preferential treatment because of his illness irked the other prisoners, and earned him the title of "His imprisoned Lordship" by the admirals, who often mocked him and played mean-spirited pranks on him.

Fearing for his mental health now that he was the sole remaining inmate, and assuming that his death was imminent, the prison directors agreed to slacken most of the remaining regulations, moving Hess to the more spacious former chapel space, giving him a water heater to allow the making of tea or coffee when he liked, and permanently unlocking his cell so that he could freely access the prison's bathing facilities and library.