Spanish Inquisition

[13] The Episcopal Inquisition was created through the papal bull Ad Abolendam ("To abolish")[14][15] at the end of the 12th century by Pope Lucius III, with the support of emperor Frederick I, to combat the Albigensian heresy in southern France.

[19] Cultural historian Américo Castro has characterized post-reconquest medieval Spain as a society of relatively peaceful co-existence (convivencia) punctuated by occasional conflict among the ruling Catholics, Jews, and Muslims.

These accusations and images could have had direct political and military consequences, especially considering that the union of two powerful kingdoms was a delicate moment that could prompt fear and violent reactions from neighbors, more so if combined with the expansion of the Ottoman Turks on the Mediterranean.

The conquest of Naples by the Gran Capitan is also proof of an interest in Mediterranean expansion and re-establishment of Spanish power in that sea that was bound to generate frictions with the Ottoman Empire and other African nations.

The creation of the Spanish Inquisition was consistent with the most important political philosophers of the Florentine School[dubious – discuss], with whom the kings were known to have contact (Guicciardini, Pico della Mirandola, Machiavelli, Segni, Pitti, Nardi, Varchi, etc.)

Both Guicciardini and Machiavelli defended the importance of centralization and unification to create a strong state capable of repelling foreign invasions and also warned of the dangers of excessive social uniformity to the creativity and innovation of a nation.

Pope Sixtus IV granted the bull Exigit sincerae devotionis affectus, permitting the monarchs to select and appoint two or three priests over forty years of age to act as inquisitors.

Torquemada eventually assumed the title of Inquisitor-General[50][51] Ferdinand II of Aragon pressured Pope Sixtus IV to agree to an Inquisition controlled by the monarchy by threatening to withdraw military support when the Turks were a threat to Rome.

[52] On 1 November 1478, Sixtus published the Papal bull, Exigit Sincerae Devotionis Affectus (Sincere Devotion Is Required), through which he gave the monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors in their kingdoms.

Sixtus IV promulgated a new bull (1482) categorically prohibiting the Inquisition's extension to Aragón, affirming that:[52] ... in Aragon, Valencia, Mallorca and Catalonia the Inquisition has for some time been moved not by zeal for the faith and the salvation of souls, but by lust for wealth, and that many true and faithful Christians, on the testimony of enemies, rivals, slaves and other lower and even less proper persons, have without any legitimate proof been thrust into secular prisons, tortured and condemned as relapsed heretics, deprived of their goods and property and handed over to the secular arm to be executed, to the peril of souls, setting a pernicious example, and causing disgust to many.

Evidence that was used to identify a crypto-Jew included the absence of chimney smoke on Saturdays (a sign the family might secretly be honoring the Sabbath), the buying of many vegetables before Passover, or the purchase of meat from a converted butcher.

[69] Although the vast majority of conversos simply assimilated into the Catholic dominant culture, a minority continued to practice Judaism in secret and gradually migrated throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, mainly to areas where Sephardic communities were already present as a result of the Alhambra Decree.

[citation needed] The War of the Alpujarras (1568–71), a general Muslim/Morisco uprising in Granada that expected to aid Ottoman disembarkation in the peninsula, ended in a forced dispersal of about half of the region's Moriscos throughout Castile and Andalusia as well as increased suspicions by Spanish authorities against this community.

"[80] Although initial estimates of the number expelled, such as those of Henri Lapeyre, reach 300,000 Moriscos (or 4% of the total Spanish population), the extent and severity of the expulsion in much of Spain has been increasingly challenged by modern historians such as Trevor J.

Disrespect to church images, and eating meat on forbidden days, were taken as signs of heresy...[92] It is estimated that a dozen Protestant Spaniards were burned alive at the stake in the later part of the sixteenth century.

[109] In 1815, Francisco Javier de Mier y Campillo, the Inquisitor General of the Spanish Inquisition and the Bishop of Almería, suppressed Freemasonry and denounced the lodges as "societies which lead to atheism, to sedition and to all errors and crimes.

Despite the repeated publication of the Indexes and a large bureaucracy of censors, the activities of the Inquisition did not impede the development of Spanish literature's "Siglo de Oro", although almost all of its major authors crossed paths with the Holy Office at one point or another.

The two forms of obvious male sterility were either due to damage to the genitals through castration or accidental wounding at war (capón) or to some genetic condition that might keep the man from completing puberty (lampiño).

That the situation was open to abuse is evident, as stands out in the memorandum that a converso from Toledo directed to Charles I: Your Majesty must provide, before all else, that the expenses of the Holy Office do not come from the properties of the condemned, because if that is the case if they do not burn they do not eat.

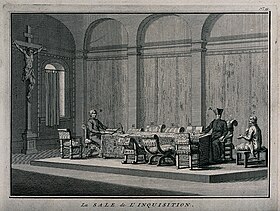

[166] Once the process concluded, the inquisitors met with a representative of the bishop and with the consultores (consultants), experts in theology or Canon Law (but not necessarily clergy themselves), which was called the consulta de fe (faith consultation/religion check).

[177][failed verification] If the sentence was condemnatory, this implied that the condemned had to participate in the ceremony of an auto de fé (more commonly known in English as an auto-da-fé) that solemnized their return to the Church (in most cases), or punishment as an impenitent heretic.

Manuel Godoy and Antonio Alcalá Galiano were openly hostile to an institution whose only role had been reduced to censorship and was the very embodiment of the Spanish Black Legend, internationally, and was not suitable to the political interests of the moment: The Inquisition?

Its old power no longer exists: the horrible authority that this bloodthirsty court had exerted in other times was reduced... the Holy Office had come to be a species of commission for book censorship, nothing more...[190]The Inquisition was first abolished during the domination of Napoleon and the reign of Joseph Bonaparte (1808–1812).

Later, during the period known as the Ominous Decade, the Inquisition was not formally re-established,[193] although, de facto, it returned under the so-called Congregation of the Meetings of Faith (Juntas da Fé), created in the dioceses by King Ferdinand VII.

Finally, on 15 July 1834, the Spanish Inquisition was definitively abolished by a Royal Decree signed by regent Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies, Ferdinand VII's liberal widow, during the minority of Isabella II and with the approval of the President of the Cabinet Francisco Martínez de la Rosa.

Data for the Aragonese Secretariat are probably complete, some small lacunae may concern only Valencia and possibly Sardinia and Cartagena, but the numbers for Castilian Secretariat—except Canaries and Galicia—should be considered as minimal due to gaps in the documentation.

Table of sentences pronounced in the public autos de fé in Spain (excluding tribunals in Sicily, Sardinia and Latin America) between 1701 and 1746:[222] According to Toby Green, the great unchecked power given to inquisitors meant that they were "widely seen as above the law",[223] and they sometimes had motives for imprisoning or executing alleged offenders that had nothing to do with punishing religious nonconformity.

Despite the existence of extensive documentation regarding the trials and procedures, and to the Inquisition's deep bureaucratization, none of these sources was studied outside of Spain, and Spanish scholars arguing against the predominant view were automatically dismissed.

This influential work describes the Spanish Inquisition as "an engine of immense power, constantly applied for the furtherance of obscurantism, the repression of thought, the exclusion of foreign ideas and the obstruction of progress.

Contemporary historians who subscribe to the idea that the image of the Inquisition in historiography has been systematically deformed by the Black Legend include Edward Peters, Philip Wayne Powell, William S. Maltby, Richard Kagan, Margaret R. Greer, Helen Rawlings, Ronnie Hsia, Lu Ann Homza, Stanley G. Payne, Andrea Donofrio, Irene Silverblatt, Christopher Schmidt-Nowara, Charles Gibson, and Joseph Pérez.