Louisiana (New Spain)

[2] Spain also took possession of the trading post of St. Louis and all of Upper Louisiana in the late 1760s, though there was little Spanish presence in the wide expanses of what they called the "Illinois Country".

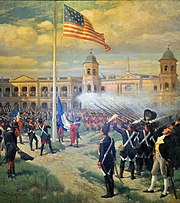

Three weeks later on 20 December, another ceremony was held at the same location in which France transferred New Orleans and the surrounding area to the United States pursuant to the Louisiana Purchase.

They covered much of the territory that now corresponds to the southern and southwestern United States, including the coast of Louisiana (see the book "Naufragios" which recounts this adventure).

Shortly before, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado's expedition left Mexico in search of the Seven Golden Cities and the Great Quivira (1540-1542).

However, the few troops led by Oñate had to retreat due to indigenous hostility and not finding any trace of gold or other typical riches of mercantile capitalism.

However, on October 10, 1765, a small detachment of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment under the command of Captain Thomas Stirling took control of the Fort Chartres fortress and its surroundings.

Spanish Louisiana stretched from the Gulf of Mexico's Coastal Plain and the areas adjacent to the Mississippi Delta to Canada's border.

Ecologically, the vast territory of Spanish Louisiana corresponded to most of what is now called the Midwest and included the following biomes: The Great Plains, largely consisting of expansive flat and gently rolling prairies roamed by herds of millions of massive American bison or cíbolos.

These prairies or great plains, covered with tall grasslands (up to 6 feet high) with deep and extensive roots, were located west of the western forests and north of the Cross Timbers, a wooded region primarily composed of deciduous trees.

And on November 3, 1770, Governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga abolished ineffective regulations on slave acquisition with his legal code.

Hence, Kaskaskia was occupied by the English, while French settlers, protected by Spain, settled in Santa Genoveva del Mississippi and San Luis de Illinois.

The English and later the Americans utilized the ancient Cahokia mound to establish a fort opposite the Spanish capital of Upper Louisiana.

Governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga transformed the expansive, nearly uninhabited, and undefended province into a thriving region with some autonomy.

Known as 'le Conciliateur', he adopted a conciliatory approach, notably freeing the leaders of the Louisiana Revolution and promoting cross-border trade with American settlers through the Mississippi.

In contrast, Bernardo de Gálvez, succeeding Unzaga y Amézaga as interim governor, declared war on Great Britain on May 8, 1779.

He defeated the British in Baton Rouge, Naches, Mobile, and Pensacola, reclaiming Florida for Spain in 1781, a feat recognized by the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

To regulate building constructions, he introduced Spanish architectural styles, resulting in arcades, courtyards, and fountains, traces of which remain evident today.

Gálvez's primary mission was to monitor events in the British colonies in North America, which were embroiled in war, and prepare the territory for a potential conflict with the United Kingdom.

During the early decades of Spanish rule, however, the population grew rapidly: according to a census conducted during O'Reilly's governance in 1769, there were 13,513 inhabitants (excluding indigenous people).

Aiming to boost agriculture and curry favor with the Creole oligarchy, Gálvez authorized the increased importation of African slaves in November 1777.

To reinforce the defensive function of this border territory, there was a drive to increase the population, partly through immigration from both Spanish nationals and foreigners, preferably Catholics.

In previous decades, settlers of German and French cultures, specifically the Acadians, had settled in the region and had played a part in the revolt against Governor Ulloa.

Governors, especially Bernardo de Gálvez, focused on curbing English smuggling and promoting monopolistic trade between the large colony and the Spanish metropolis, and occasionally with France.

Over the next decade, thousands of migrants from the island landed there, including ethnic Europeans, free people of color, and African slaves, some of the latter brought in by the white elites.

[7] One of the reasons the Spanish Monarchy, which during its height largely adhered to mercantilism, did not prioritize such vast and fertile territories (especially in agriculture and livestock) was the lack of significant gold, silver, or precious stone mines.

Although significant gold and silver deposits were eventually discovered in the mountains of present-day Colorado, this discovery came late—just around the time the territory was handed over to the United States.

By the end of Spanish rule, significant portions of Lower Louisiana started cultivating cotton, which would become a globally essential textile until the mid-20th century.

Through the treaty, the Americans staked their claims on the southwestern area of today's state of Louisiana, including regions like Natchitoches and Lake Charles, in exchange for recognizing the boundaries at the Red River and Nexpentle/Arkansas up to the 42°N parallel and the main meridians connecting these points.

In return, Spain, which by then was rapidly losing its grip on the American continent, retained control over the entirety of New Mexico, all of Texas, and nearly two-thirds of what is present-day Colorado.

Spain also gave up its claim on the western part of the current U.S. state of Louisiana, including the Neutral Zone between the Sabine River and the Hondo Creek.