Hernando de Soto

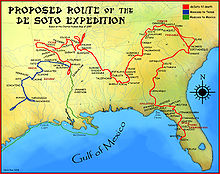

It ranged throughout what is now the southeastern United States, searching both for gold, which had been reported by various Native American tribes and earlier coastal explorers, and for a passage to China or the Pacific coast.

De Soto died in 1542 on the banks of the Mississippi River;[6] sources disagree on the exact location, whether it was what is now Lake Village, Arkansas, or Ferriday, Louisiana.

With Christopher Columbus's discovery of new lands (which he thought to be East Asia) across the ocean to the west, young men were attracted to rumors of adventure, glory and wealth.

[1]: 135 Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and ruthless schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto's hallmarks during the conquest of Central America.

Bringing his own men on ships which he hired, de Soto joined Francisco Pizarro at his first base of Tumbes shortly before departure for the interior of present-day Peru.

When Pizarro's men attacked Atahualpa and his guard the next day (the Battle of Cajamarca), de Soto led one of the three groups of mounted soldiers.

[10] During 1533, the Spanish held Atahualpa captive in Cajamarca for months while his subjects paid for his ransom by filling a room with gold and silver objects.

In 1535 King Charles awarded Diego de Almagro, Francisco Pizarro's partner, the governorship of the southern portion of the Inca Empire.

With tons of heavy armor and equipment, they also carried more than 500 head of livestock, including 237 horses and 200 pigs, for their planned four-year continental expedition.

On 10 May 1539, he wrote in his will: That a chapel be erected within the Church of San Miguel in Jerez de Los Caballeros, Spain, where De Soto grew up, at a cost of 2,000 ducats, with an altarpiece featuring the Virgin Mary, Our Lady of the Conception, that his tomb be covered in a fine black broadcloth topped by a red cross of the Order of the Knights of Santiago, and on special occasions a pall of black velvet with the De Soto coat of arms be placed on the altar; that a chaplain be hired at the salary of 12,000 maravedis to perform five masses every week for the souls of De Soto, his parents, and wife; that thirty masses be said for him the day his body was interred, and twenty for our Lady of the Conception, ten for the Holy Ghost, sixty for souls in purgatory and masses for many others as well; that 150000 maravedis be given annually to his wife Isabel for her needs and an equal amount used yearly to marry off three orphan damsels...the poorest that can be found," to assist his wife and also serve to burnish the memory of De Soto as a man of charity and substance.

A committee chaired by the anthropologist John R. Swanton published The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission in 1939.

Among other locations, Manatee County, Florida, claims an approximate landing site for de Soto and has a national memorial recognizing that event.

[18] In the early 21st century, the first part of the expedition's course, up to de Soto's battle at Mabila (a small fortress town in present-day central Alabama[19]), is disputed only in minor details.

[citation needed] The Governor Martin Site at the former Apalachee village of Anhaica, located about a mile east of the present-day Florida state capitol in Tallahassee, has been documented as definitively associated with de Soto's expedition.

[22] Many archaeologists believe the Parkin Archeological State Park in northeast Arkansas was the main town for the indigenous province of Casqui, which de Soto had recorded.

"[29] The chronicles describe de Soto's trail in relation to Havana, from which they sailed; the Gulf of Mexico, which they skirted while traveling inland then turned back to later; the Atlantic Ocean, which they approached during their second year; high mountains, which they traversed immediately thereafter; and dozens of other geographic features along their way, such as large rivers and swamps, at recorded intervals.

Hernando de Soto's army seized the food stored in the villages, captured women to be used as slaves for the soldiers' sexual gratification, and forced men and boys to serve as guides and bearers.

The bay was named for events of the 1527 Narváez expedition, the members of which, dying of starvation, killed and ate their horses while building boats for escape by the Gulf of Mexico.

From their winter location in the western panhandle of Florida, having heard of gold being mined "toward the sun's rising", the expedition turned northeast through what is now the modern state of Georgia.

[36][37] Based on archaeological finds made in 2009 at a remote, privately owned site near the Ocmulgee River, researchers believe that de Soto's expedition stopped in Telfair County.

Artifacts found here include nine glass trade beads, some of which bear a chevron pattern made in Venice for a limited period of time and believed to be indicative of the de Soto expedition.

There the expedition recorded being received by a female chief (The Lady of Cofitachequi), who gave her tribe's pearls, food and other goods to the Spanish soldiers.

Swanton's final report, published by the Smithsonian, remains an important resource[40] but Hudson's reconstruction of the route was conducted 40 years later and benefited from considerable advances in archaeological methods.

[41] De Soto's expedition spent another month in the Coosa chiefdom a vassal to Tuskaloosa, who was the paramount chief,[citation needed] believed to have been connected to the large and complex Mississippian culture, which extended throughout the Mississippi Valley and its tributaries.

[42] The expedition began making plans to leave the next day, and Tuskaloosa gave in to de Soto's demands, providing bearers for the Spaniards.

[61] De Soto had deceived the local natives into believing that he was a deity, specifically an "immortal Son of the Sun,"[56] to gain their submission without conflict.

According to one source, de Soto's men hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the middle of the Mississippi River during the night.

[57] De Soto's expedition had explored La Florida for three years without finding the expected treasures or a hospitable site for colonization.

The leaders came to a consensus (although not total) to end the expedition and try to find a way home, either down the Mississippi River, or overland across Texas to the Spanish colony of Mexico City.

But, after they reached Mexico City and the Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza offered to lead another expedition to La Florida, few of the survivors volunteered.

The Spanish caption reads:

"HERNANDO DE SOTO: Extremaduran, one of the discoverers and conquerors of Peru: he travelled across all of Florida and defeated its previously invincible natives, he died on his expedition in the year 1542 at the age of 42".