Second Spanish Republic

During this time and the subsequent two years of constitutional government, known as the Reformist Biennium, Manuel Azaña's executive initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would modernize the country.

Armed revolutionaries managed to take the whole province of Asturias, killing policemen, clerics, and businessmen and destroying religious buildings and part of the University of Oviedo.

[9][10] Amidst the wave of political violence that broke out after the triumph of the Popular Front in the February 1936 elections, a group of Guardia de Asalto and other leftist militiamen mortally shot José Calvo Sotelo, one of the leaders of the opposition, on 12 July 1936.

The first was led by left-wing republican José Giral (from July to September 1936); a revolution inspired mostly by libertarian socialist, anarchist and communist principles broke out in its territory.

The Constitution guaranteed a wide range of civil liberties, but it opposed key beliefs of the right wing, which was very rooted in rural areas, and desires of the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, which was stripped of schools and public subsidies.

In the summer of 1936, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, it became largely irrelevant after the authority of the Republic was superseded in many places by revolutionary socialists and anarchists on one side, and Nationalists on the other.

In November 1932, Miguel de Unamuno, one of the most respected Spanish intellectuals, rector of the University of Salamanca, and himself a Republican, publicly raised his voice to protest.

But now we have something worse: a police force which is grounded only on a general sense of panic and on the invention of non-existent dangers to cover up this over-stepping of the law.

[7] The revolutionary soviets set up by the miners attempted to impose order on the areas under their control, and the moderate socialist leadership of Ramón González Peña and Belarmino Tomás took measures to restrain violence.

With this rebellion against an established political legitimate authority, the Socialists showed identical repudiation of representative institutional system that anarchists had practiced.

[31] The Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga, an Azaña supporter and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco, is the author of a sharp critical reflection against the participation of the left in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable.

At the same time, the involvement of the Centrist government party in the Straperlo and Nombela scandals deeply weakened it, further polarising political differences between right and left.

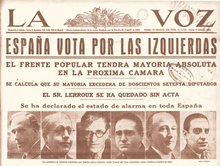

[33] In line with Payne's point of view, in 2017, two Spanish Scholars, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García, published the result of a research where they concluded that the 1936 elections were rigged.

[36] In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured, while fifty churches and seventy right wing political centres were attacked or set ablaze.

This was not a coup attempt, but more of a "police action" akin to Asturias, as Franco believed the post-election environment could become violent and was trying to quell the perceived leftist threat.

[40] The right reacted as if radical communists had taken control, despite the new cabinet's moderate composition; they were shocked by the revolutionary masses taking to the streets and the release of prisoners.

Convinced that the left was no longer willing to follow the rule of law and that its vision of Spain was under threat, the right abandoned the parliamentary option and began to conspire as to how to best overthrow the republic, rather than taking control of it.

"[43] In June 1936, Miguel de Unamuno, disenchanted with the unfolding of the events, told a reporter who published his statement in El Adelanto that President Manuel Azaña should commit suicide as a patriotic act.

[44] On 12 July 1936, Lieutenant José Castillo, an important member of the anti-fascist military organisation Unión Militar Republicana Antifascista (UMRA), was shot by Falangist gunmen.

In response, a group of Guardia de Asalto and other leftist militiamen led by Civil Guard Fernando Condés, after getting the approval of the minister of interior to illegally arrest a list of members of parliament, went to right-wing opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo's house in the early hours of 13 July on a revenge mission.

The Falange and other right-wing individuals, including Juan de la Cierva, had already been conspiring to launch a military coup d'état against the government, to be led by senior army officers.

[47] When the antifascist Castillo and the anti-socialist Calvo Sotelo were buried on the same day in the same Madrid cemetery, fighting between the Police Assault Guard and fascist militias broke out in the surrounding streets, resulting in four more deaths.

[53] Within hours of learning of the murder and the reaction, Franco, who until then had not been involved in the conspiracies, changed his mind on rebellion and dispatched a message to Mola to display his firm commitment.

[54] Three days later (17 July), the coup d'état began more or less as it had been planned, with an army uprising in Spanish Morocco, which then spread to several regions of the country.

The 1931 Constitution would be suspended, replaced by a new "constituent parliament" which would be chosen by a new politically purged electorate, who would vote on the issue of republic versus monarchy.

Violence would be required to destroy opposition to the coup, though it seems Mola did not envision the mass atrocities and repression that would ultimately manifest during the civil war.

[56][57] Of particular importance to Mola was ensuring the revolt was at its core an Army affair, one that would not be subject to special interests and that the coup would make the armed forces the basis for the new state.

Before long the professional Army of Africa had much of the south and west under the control of the rebels and by October 1936, Time Magazine declared that "façade of the Spanish Republic was crumbling".

[62] Although both sides received foreign military aid, the help that Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany (as part of the Italian military intervention in Spain and the German involvement in the Spanish Civil War), and neighbouring Portugal gave the rebels was much greater and more effective than the assistance that the Republicans received from the USSR, Mexico, and volunteers of the International Brigades.

This greatly contributed to Spain's economic hardships, as their center of industry was located on the opposite side of the country from their resource reserves, resulting in immense transportation costs due to the mountainous Spanish terrain.