Spatial disorientation

Spatial disorientation is the inability to determine position or relative motion, commonly occurring during periods of challenging visibility, since vision is the dominant sense for orientation.

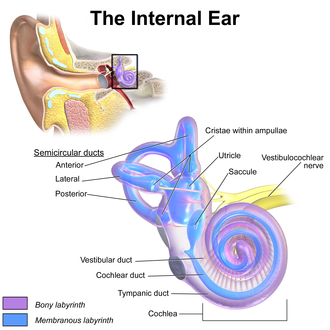

Spatial orientation in flight is difficult to achieve because numerous sensory stimuli (visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive) vary in magnitude, direction, and frequency.

[2] In 1926, Ocker was subjected to a Bárány chair equilibrium test by Dr. David A. Myers at Crissy Field; the resulting duplication of the somatogyral illusion he had experienced and a subsequent re-test, which he passed using the turn indicator,[3] led him to develop and champion instrumented flight.

[5]: 8 In 1965, the Federal Aviation Agency of the United States issued Advisory Circular AC 60-4, warning pilots about the hazards of spatial disorientation, which may result from operation under visual flight rules in conditions of marginal visibility.

[8] Spatial-D and G-force induced loss of consciousness (g-LOC) are two of the most common causes of death from human factors in military aviation.

[citation needed] The three-dimensional environment of flight is unfamiliar to the human body, creating sensory conflicts and illusions that make spatial orientation difficult and sometimes impossible to achieve.

[citation needed] A gradual change in any direction of movement may not be strong enough to activate the vestibular system, so the pilot may not realize that the aircraft is accelerating, decelerating, or banking.

[8] Some examples of this include the inertial forces experienced during a vertical take-off in a helicopter or following the sudden opening of a parachute after a free fall.

[8] Typically, the Head-Up illusion occurs during take-off, as a strong linear acceleration is used to generate lift over the wing and flaps.

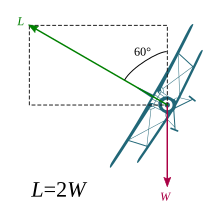

Without a visual reference, the pilot may assume from the vestibular system the nose has pitched up and command a dive; if this occurs during take-off, the aircraft may not have sufficient altitude to recover before crashing into the ground.

If the aircraft enters an unnoticed, prolonged turn gradually, then suddenly returns to level flight, the leans may result.

The gradual turn sets the fluid into the semicircular canals into motion, and rotational acceleration of two degrees per second (or less) cannot be detected.

[citation needed] If the pilot is not proficient in the use of gyroscopic flight instruments, these errors will build up to a point that control of the aircraft is lost, usually in a steep, diving turn known as a graveyard spiral.

During the entire time, leading up to and well into the maneuver, the pilot remains unaware of the turning, believing that the aircraft is maintaining straight flight.

[15]: 125 In a 1954 study (180 – Degree Turn Experiment), the University of Illinois Institute of Aviation found that 19 out of 20 non-instrument-rated subject pilots went into a graveyard spiral soon after entering simulated instrument conditions.