Forty acres and a mule

[29] This plan—initiated by John A. Dix and supported by Captain Wilder and Secretary of War Stanton—drew negative reactions from Republicans who wanted to avoid connecting northward black migration with the newly announced Emancipation Proclamation.

The President then wrote and handed to me the following card : I shall be obliged if the Secretary of the Treasury will in his discretion give Mr. Pierce such instructions in regard to Port Royal contrabands as may seem judicious.

[47] These sympathetic Northerners quickly recruited a boatload (53 chosen from a pool of applicants several times larger) of Ivy League and divinity school graduates who set off for Port Royal on March 3, 1862.

[49] Joy turned to sorrow when, on May 12 Union soldiers arrived to draft all able-bodied black men previously liberated on April 13, 1862, by General David Hunter who proclaimed slavery abolished in Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama.

[54] On balance, however, the white sponsors of the Experiment had perceived positive results; businessman John Murray Forbes in May 1862 called it "a decided success", announcing that Blacks would indeed work in exchange for wages.

[100] Criticism of Treasury Department profiteering by General John Eaton and journalists who witnessed the new form of plantation labor influenced public opinion in the North and pressured Congress to support direct control of land by freedmen.

[104] Davis allowed several hundred slaves to eat nutritious food, live in well-built cottages, receive medical care, and resolve their disputes in a weekly "Hall of Justice" court.

[106][107] Black refugees who had gathered in Vicksburg moved en masse to Davis Bend under the auspices of the Freedman's Department (an agency created by the military prior to Congressional authorization of the "Freedmen's Bureau", discussed below).

In a petition signed by 56 farmers (including Montgomery) and published in the New Orleans Tribune:[111] At the commencement of our present year, this plantation was, in compliance with an order of our Post Commander, deprived of horses, mules, oxen and farming utensils of every description, very much of which had been captured and brought into Union lines by the undersigned; in consequence of which deprivations, we were, of course, reduced to the necessity of buying everything necessary for farming, and having thus far succeeded in performing by far the most expensive and laborious part of our work, we are prepared to accomplish the ginning, pressing, weighing, marking, consigning, etc., in a business-like order if allowed to do so.From 1863 to 1865, Congress debated what policies it might adopt to address the social issues that would confront the South after the war.

After Johnson ordered the Bureau to restore the estate of a complaining Tennessee plantation owner, General Joseph S. Fullerton suggested to at least one subordinate that Circular #13 "will not be observed for the present".

Clinton B. Fisk, Assistant Commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau for Kentucky and Tennessee, had announced at a black political assembly: "They must not only have freedom but homes of their own, thirty or forty acres, with mules, cottages, and schoolhouses etc."

Volunteers were promised 40 acres of land and a job in the mines; Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy, whom Lincoln had appointed to oversee the plan, had also purchased mules, yokes, tools, wagons, seeds, and other supplies to support a potential colony.

[157][158] In December 1865, Congress began to debate the "Second Freedmen's Bureau bill", which would have opened three million acres of unoccupied public land in Florida, Mississippi, and Arkansas for homesteading.

The fact that members of the elite predominated among black officeholders during Reconstruction also meant they rarely pushed this issue in Congress or state legislatures (not that it had much chance of passing even if they had, due to white majorities in these bodies).

But (with support from Stanton, who felt comfortable with a literal interpretation of the phrase "mutually satisfactory")[212][213] appointed a sympathetic captain, Alexander P. Ketchum, to form a commission overseeing the transition.

"[219][220] Soldiers continued to evict settlers and enforce work agreements, leading in 1867 to a large-scale armed standoff between the Army and a group of farmers who would not renew their contract with a plantation owner.

[233] Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner continued to support land reform for freedpeople, but were opposed by a large bloc of politicians who did not want to violate property rights or redistribute capital.

They were intended to address the immediate problem of dealing with the tens of thousands of black refugees who had joined Sherman's march in search of protection and sustenance, and "to assure the harmony of action in the area of operations.

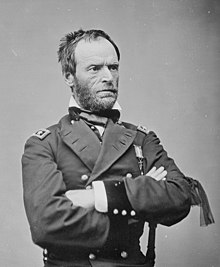

[237] General Sherman issued his orders four days after meeting with twenty local black ministers and lay leaders and with U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in Savannah, Georgia.

He cannot be subjected to conscription or forced military service, save by the written orders of the highest military authority of the Department, under such regulations as the President or Congress may prescribe; domestic servants, blacksmiths, carpenters, and other mechanics will be free to select their own work and residence, but the young and able-bodied negroes must be encouraged to enlist as soldiers in the service of the United States, to contribute their share toward maintaining their own freedom and securing their rights as citizens of the United States.

The bounties paid on enlistment may, with the consent of the recruit, go to assist his family and settlement in procuring agricultural implements, seed, tools, boats, clothing, and other articles necessary for their livelihood.

Whenever a negro has enlisted in the military service of the United States he may locate his family in any one of the settlements at pleasure and acquire a homestead and all other rights and privileges of a settler as though present in person.

The same general officer will also be charged with the enlistment and organization of the negro recruits and protecting their interests while absent from their settlements, and will be governed by the rules and regulations prescribed by the War Department for such purpose.

According to Henry Louis Gates Jr.: The promise was the first systematic attempt to provide a form of reparations to newly freed slaves, and it was astonishingly radical for its time, proto-socialist in its implications.

In fact, such a policy would be radical in any country today: the federal government's massive confiscation of private property – some 400,000 acres – formerly owned by Confederate land owners, and its methodical redistribution to former black slaves.

In Pigford v. Glickman (1999), District Court Judge Paul L. Friedman ruled in favor of the farmers and ordered the USDA to pay financial damages for loss of land and revenue.

In his opinion, federal judge Paul L. Friedman ruled that the United States Department of Agriculture had discriminated against African American farmers and wrote: "Forty acres and a mule.

However, strictly speaking, the various policies offering "forty acres" provided land for political and economic reasons—and with a price tag—and not as unconditional compensation for lifetimes of unpaid labor.

[266][267] 'Forty acres and a mule', that delightful bit of myopic mythology so often ascribed to the newly freed in the Reconstruction period, at least in South Carolina during the spring and summer of 1865, represented far more than the chimerical rantings of the ignorant darkies, irresponsible soldiers", and radical politicians.

By the Spring of 1865, this program was well underway, and after August any well-informed intelligent observer in South Carolina would have concluded, as did the Negroes, that some considerable degree of permanent land division was highly probable.