Sphere packing

Arrangements in which the spheres do not form a lattice (often referred to as irregular) can still be periodic, but also aperiodic (properly speaking non-periodic) or random.

Because of their high degree of symmetry, lattice packings are easier to classify than non-lattice ones.

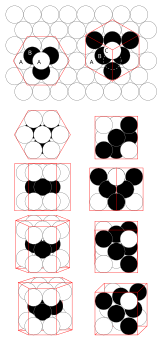

The other is called hexagonal close packing ("HCP"), where the layers are alternated in the ABAB...

[dubious – discuss] But many layer stacking sequences are possible (ABAC, ABCBA, ABCBAC, etc.

[3] In 1998, Thomas Callister Hales, following the approach suggested by László Fejes Tóth in 1953, announced a proof of the Kepler conjecture.

[5] Packings where all spheres are constrained by their neighbours to stay in one location are called rigid or jammed.

However, the sixth sphere placed in this way will render the structure inconsistent with any regular arrangement.

This results in the possibility of a random close packing of spheres which is stable against compression.

Recent research predicts analytically that it cannot exceed a density limit of 63.4%[9] This situation is unlike the case of one or two dimensions, where compressing a collection of 1-dimensional or 2-dimensional spheres (that is, line segments or circles) will yield a regular packing.

[12] In 2016, Maryna Viazovska announced a proof that the E8 lattice provides the optimal packing (regardless of regularity) in eight-dimensional space,[13] and soon afterwards she and a group of collaborators announced a similar proof that the Leech lattice is optimal in 24 dimensions.

[14] This result built on and improved previous methods which showed that these two lattices are very close to optimal.

[15] The new proofs involve using the Laplace transform of a carefully chosen modular function to construct a radially symmetric function f such that f and its Fourier transform f̂ both equal 1 at the origin, and both vanish at all other points of the optimal lattice, with f negative outside the central sphere of the packing and f̂ positive.

Then, the Poisson summation formula for f is used to compare the density of the optimal lattice with that of any other packing.

"[17] Another line of research in high dimensions is trying to find asymptotic bounds for the density of the densest packings.

[19] In a 2023 preprint, Marcelo Campos, Matthew Jenssen, Marcus Michelen and Julian Sahasrabudhe improved the lower bound of the maximal density to

The density of this interstitial packing depends sensitively on the radius ratio, but in the limit of extreme size ratios, the smaller spheres can fill the gaps with the same density as the larger spheres filled space.

[26] In many chemical situations such as ionic crystals, the stoichiometry is constrained by the charges of the constituent ions.

[27] Although the concept of circles and spheres can be extended to hyperbolic space, finding the densest packing becomes much more difficult.

[28] Despite this difficulty, K. Böröczky gives a universal upper bound for the density of sphere packings of hyperbolic n-space where n ≥ 2.

[29] In three dimensions the Böröczky bound is approximately 85.327613%, and is realized by the horosphere packing of the order-6 tetrahedral honeycomb with Schläfli symbol {3,3,6}.

[30] In addition to this configuration at least three other horosphere packings are known to exist in hyperbolic 3-space that realize the density upper bound.

In the case of 3-dimensional Euclidean space, non-trivial upper bounds on the number of touching pairs, triplets, and quadruples[32] were proved by Karoly Bezdek and Samuel Reid at the University of Calgary.

For further details on these connections, see the book Sphere Packings, Lattices and Groups by Conway and Sloane.