Apollonian gasket

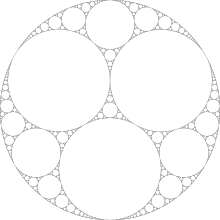

In mathematics, an Apollonian gasket or Apollonian net is a fractal generated by starting with a triple of circles, each tangent to the other two, and successively filling in more circles, each tangent to another three.

(black in the figure), that are each tangent to the other two, but that do not have a single point of triple tangency.

The construction continues by adding six more circles, one in each of these six curved triangles, tangent to its three sides.

These in turn create 18 more curved triangles, and the construction continues by again filling these with tangent circles, ad infinitum.

When there are two lines, they must be parallel, and are considered to be tangent at a point at infinity.

[2][3] Because it has a well-defined fractional dimension, even though it is not precisely self-similar, it can be thought of as a fractal.

Any two triples of mutually tangent circles in an Apollonian gasket may be mapped into each other by a Möbius transformation, and any two Apollonian gaskets may be mapped into each other by a Möbius transformation.

In particular, for any two tangent circles in any Apollonian gasket, an inversion in a circle centered at the point of tangency (a special case of a Möbius transformation) will transform these two circles into two parallel lines, and transform the rest of the gasket into the special form of a gasket between two parallel lines.

However, some triples of circles can generate Apollonian gaskets with higher symmetry than the initial triple; this happens when the same gasket has a different and more-symmetric set of generating circles.

Particularly symmetric cases include the Apollonian gasket between two parallel lines (with infinite dihedral symmetry), the Apollonian gasket generated by three congruent circles in an equilateral triangle (with the symmetry of the triangle), and the Apollonian gasket generated by two circles of radius 1 surrounded by a circle of radius 2 (with two lines of reflective symmetry).

If any four mutually tangent circles in an Apollonian gasket all have integer curvature (the inverse of their radius) then all circles in the gasket will have integer curvature.

[5] Since the equation relating curvatures in an Apollonian gasket, integral or not, is

it follows that one may move from one quadruple of curvatures to another by Vieta jumping, just as when finding a new Markov number.

The first few of these integral Apollonian gaskets are listed in the following table.

The table lists the curvatures of the largest circles in the gasket.

are a root quadruple (the smallest in some integral circle packing) if

[5] This relationship can be used to find all the primitive root quadruples with a given negative bend

[6] The following Python code demonstrates this algorithm, producing the primitive root quadruples listed above.

The curvatures appearing in a primitive integral Apollonian circle packing must belong to a set of six or eight possible residues classes modulo 24, and numerical evidence supported that any sufficiently large integer from these residue classes would also be present as a curvature within the packing.

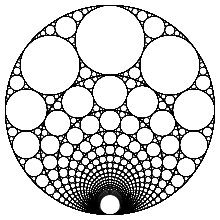

[8][9] There are multiple types of dihedral symmetry that can occur with a gasket depending on the curvature of the circles.

Whenever two of the largest five circles in the gasket have the same curvature, that gasket will have D1 symmetry, which corresponds to a reflection along a diameter of the bounding circle, with no rotational symmetry.

If the three circles with smallest positive curvature have the same curvature, the gasket will have D3 symmetry, which corresponds to three reflections along diameters of the bounding circle (spaced 120° apart), along with three-fold rotational symmetry of 120°.

The figure at left is an integral Apollonian gasket that appears to have D3 symmetry.

The same figure is displayed at right, with labels indicating the curvatures of the interior circles, illustrating that the gasket actually possesses only the D1 symmetry common to many other integral Apollonian gaskets.

The following table lists more of these almost-D3 integral Apollonian gaskets.

The sequence has some interesting properties, and the table lists a factorization of the curvatures, along with the multiplier needed to go from the previous set to the current one.

The absolute values of the curvatures of the "a" disks obey the recurrence relation a(n) = 4a(n − 1) − a(n − 2) (sequence A001353 in the OEIS), from which it follows that the multiplier converges to √3 + 2 ≈ 3.732050807.

For any integer n > 0, there exists an Apollonian gasket defined by the following curvatures: (−n, n + 1, n(n + 1), n(n + 1) + 1).

Although the Apollonian gasket is named for Apollonius of Perga -- because of its construction's dependence on the solution to the problem of Apollonius -- the earliest description of the gasket is from 1706 by Leibniz in a letter to Des Bosses.

[10] The first modern definition of the Apollonian gasket is given by Kasner and Supnick.