Spherical trigonometry

Spherical trigonometry is of great importance for calculations in astronomy, geodesy, and navigation.

The subject came to fruition in Early Modern times with important developments by John Napier, Delambre and others, and attained an essentially complete form by the end of the nineteenth century with the publication of Todhunter's textbook Spherical trigonometry for the use of colleges and Schools.

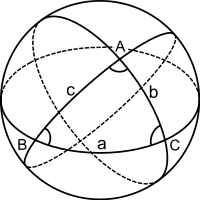

Two-sided spherical polygons—lunes, also called digons or bi-angles—are bounded by two great-circle arcs: a familiar example is the curved outward-facing surface of a segment of an orange.

Three arcs serve to define a spherical triangle, the principal subject of this article.

A very important theorem (Todhunter,[1] Art.27) proves that the angles and sides of the polar triangle are given by

These identities generalize the cosine rule of plane trigonometry, to which they are asymptotically equivalent in the limit of small interior angles.

These identities approximate the sine rule of plane trigonometry when the sides are much smaller than the radius of the sphere.

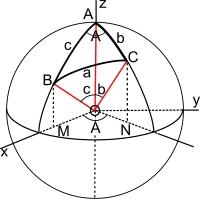

He also gives a derivation using simple coordinate geometry and the planar cosine rule (Art.60).

This equation can be re-arranged to give explicit expressions for the angle in terms of the sides:

Since the right hand side is invariant under a cyclic permutation of a, b, and c the spherical sine rule follows immediately.

Text books on geodesy[2] and spherical astronomy[3] give different proofs and the online resources of MathWorld provide yet more.

When any three of the differentials da, db, dc, dA, dB, dC are known, the following equations, which are found by differentiating the cosine rule and using the sine rule, can be used to calculate the other three by elimination:[6]

The cotangent, or four-part, formulae relate two sides and two angles forming four consecutive parts around the triangle, for example (aCbA) or BaCb).

(Todhunter,[1] Art.52) Taking quotients of these yields the law of tangents, first stated by Persian mathematician Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274),

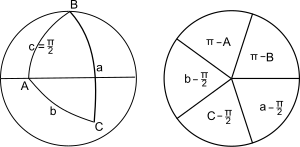

When one of the angles, say C, of a spherical triangle is equal to π/2 the various identities given above are considerably simplified.

The remaining parts can then be drawn as five ordered, equal slices of a pentagram, or circle, as shown in the above figure (right).

A quadrantal spherical triangle is defined to be a spherical triangle in which one of the sides subtends an angle of π/2 radians at the centre of the sphere: on the unit sphere the side has length π/2.

The case of five given elements is trivial, requiring only a single application of the sine rule.

In general it is better to choose methods that avoid taking an inverse sine because of the possible ambiguity between an angle and its supplement.

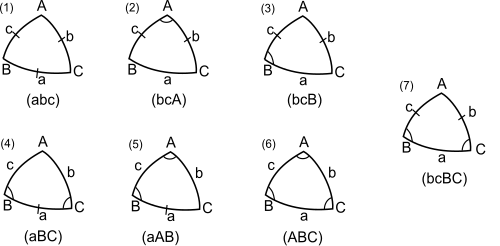

[11] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was the first to list the six distinct cases (2–7 in the diagram) of a right triangle in spherical trigonometry.

Then use Napier's rules to solve the triangle △ACD: that is use AD and b to find the side DC and the angles C and ∠DAC.

Problems and solutions may have to be examined carefully, particularly when writing code to solve an arbitrary triangle.

Consider an N-sided spherical polygon and let An denote the n-th interior angle.

For the case of a spherical triangle with angles A, B, and C this reduces to Girard's theorem

where E is the amount by which the sum of the angles exceeds π radians, called the spherical excess of the triangle.

[13] An earlier proof was derived, but not published, by the English mathematician Thomas Harriot.

For example, an octant of a sphere is a spherical triangle with three right angles, so that the excess is π/2.

In practical applications it is often small: for example the triangles of geodetic survey typically have a spherical excess much less than 1' of arc.

[14] On the Earth the excess of an equilateral triangle with sides 21.3 km (and area 393 km2) is approximately 1 arc second.

The area of a polygon can be calculated from individual quadrangles of the above type, from (analogously) individual triangle bounded by a segment of the polygon and two meridians,[15] by a line integral with Green's theorem,[16] or via an equal-area projection as commonly done in GIS.