Spherical harmonics

In mathematics and physical science, spherical harmonics are special functions defined on the surface of a sphere.

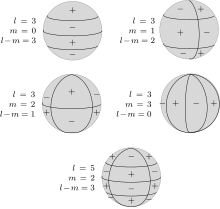

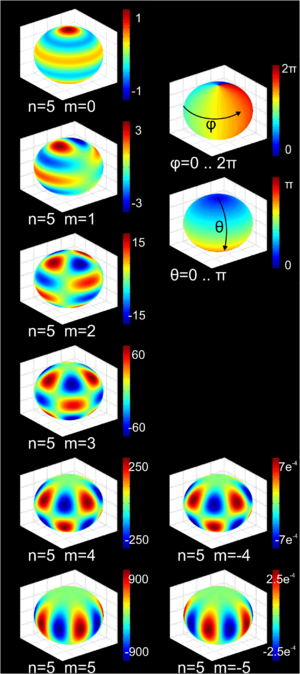

Like the sines and cosines in Fourier series, the spherical harmonics may be organized by (spatial) angular frequency, as seen in the rows of functions in the illustration on the right.

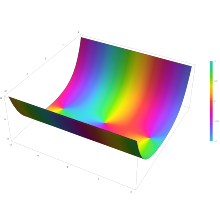

Despite their name, spherical harmonics take their simplest form in Cartesian coordinates, where they can be defined as homogeneous polynomials of degree

In 3D computer graphics, spherical harmonics play a role in a wide variety of topics including indirect lighting (ambient occlusion, global illumination, precomputed radiance transfer, etc.)

Spherical harmonics were first investigated in connection with the Newtonian potential of Newton's law of universal gravitation in three dimensions.

Subsequently, in his 1782 memoir, Laplace investigated these coefficients using spherical coordinates to represent the angle γ between x1 and x.

Many aspects of the theory of Fourier series could be generalized by taking expansions in spherical harmonics rather than trigonometric functions.

This was a boon for problems possessing spherical symmetry, such as those of celestial mechanics originally studied by Laplace and Legendre.

The prevalence of spherical harmonics already in physics set the stage for their later importance in the 20th century birth of quantum mechanics.

is an associated Legendre polynomial, N is a normalization constant,[4] and θ and φ represent colatitude and longitude, respectively.

In fact, for any such solution, rℓ Y(θ, φ) is the expression in spherical coordinates of a homogeneous polynomial

in a ball centered at the origin is a linear combination of the spherical harmonic functions multiplied by the appropriate scale factor rℓ,

In quantum mechanics, Laplace's spherical harmonics are understood in terms of the orbital angular momentum[5]

Laplace's spherical harmonics are the joint eigenfunctions of the square of the orbital angular momentum and the generator of rotations about the azimuthal axis:

The geodesy[12] and magnetics communities never include the Condon–Shortley phase factor in their definitions of the spherical harmonic functions nor in the ones of the associated Legendre polynomials.

As is known from the analytic solutions for the hydrogen atom, the eigenfunctions of the angular part of the wave function are spherical harmonics.

This is why the real forms are extensively used in basis functions for quantum chemistry, as the programs don't then need to use complex algebra.

In naming this generating function after Herglotz, we follow Courant & Hilbert 1962, §VII.7, who credit unpublished notes by him for its discovery.

The spherical harmonics have deep and consequential properties under the operations of spatial inversion (parity) and rotation.

If the coefficients decay in ℓ sufficiently rapidly — for instance, exponentially — then the series also converges uniformly to f. A square-integrable function

[18] The result can be proven analytically, using the properties of the Poisson kernel in the unit ball, or geometrically by applying a rotation to the vector y so that it points along the z-axis, and then directly calculating the right-hand side.

Let Yj be an arbitrary orthonormal basis of the space Hℓ of degree ℓ spherical harmonics on the n-sphere.

is given as a constant multiple of the appropriate Gegenbauer polynomial: Combining (2) and (3) gives (1) in dimension n = 2 when x and y are represented in spherical coordinates.

A variety of techniques are available for doing essentially the same calculation, including the Wigner 3-jm symbol, the Racah coefficients, and the Slater integrals.

, the real and imaginary components of the associated Legendre polynomials each possess ℓ−|m| zeros, each giving rise to a nodal 'line of latitude'.

, the trigonometric sin and cos functions possess 2|m| zeros, each of which gives rise to a nodal 'line of longitude'.

[24] Let Pℓ denote the space of complex-valued homogeneous polynomials of degree ℓ in n real variables, here considered as functions

The space Hℓ of spherical harmonics of degree ℓ is a representation of the symmetry group of rotations around a point (SO(3)) and its double-cover SU(2).

Thus as an irreducible representation of SO(3), Hℓ is isomorphic to the space of traceless symmetric tensors of degree ℓ.

More generally, the analogous statements hold in higher dimensions: the space Hℓ of spherical harmonics on the n-sphere is the irreducible representation of SO(n+1) corresponding to the traceless symmetric ℓ-tensors.

![{\displaystyle \Re [Y_{\ell m}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fe4514a0a6a49a33432a4bf36efe1f6fa05cb3dc)