Spirit of St. Louis

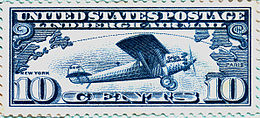

[1] Lindbergh took off in the Spirit from Roosevelt Airfield in Garden City, New York, and landed 33 hours, 30 minutes later at Aéroport Le Bourget in Paris, a distance of approximately 3,600 miles (5,800 km).

It is known, however, that Hawley Bowlus was the factory manager who oversaw construction of the Ryan NYP, and that Mahoney was the sole owner at the time of Donald A.

Although what was actually paid to Ryan Airlines for the project is not clear, Mahoney agreed to build the plane for $6,000 and said that there would be no profit; he offered an engine, instruments, etc.

Lindbergh arrived in San Diego on February 23 and toured the factory with Mahoney, meeting Bowlus, chief engineer Donald Hall, and sales manager A. J. Edwards.

"[citation needed] He then went to the airfield to familiarize himself with a Ryan aircraft, either an M-1 or an M-2, then telegraphed his St. Louis backers and recommended the deal, which was quickly approved.

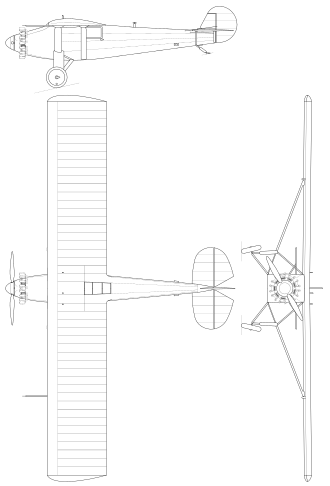

Powered by a Wright Whirlwind J-5C 223-hp radial engine, it had a 14 m (46-foot) wingspan, 3 m (10 ft) longer than the M-1, to accommodate the heavy load of 1,610 L (425 gal) of fuel.

In his 1927 book We, Lindbergh acknowledged the builders' achievement with a photograph captioned "The Men Who Made the Plane", identifying: "B. Franklin Mahoney, president, Ryan Airlines", Bowlus, Hall and Edwards standing with the aviator in front of the completed aircraft.

Lindbergh believed that a flight made in a single-seat monoplane designed around the dependable Wright J-5 Whirlwind radial engine provided the best chance of success.

The Ryan NYP had a total fuel capacity of 450 U.S. gallons (1,700 L; 370 imp gal) or 2,710 pounds (1,230 kg) of gasoline, which was necessary in order to have the range to make the anticipated flight non-stop.

[6] Lindbergh modified the design of the plane's "trombone struts" attached to the landing gear to provide a wider wheelbase in order to accommodate the weight of the fuel.

This arrangement improved the center of gravity and reduced the risk of the pilot being crushed to death between the main tank and the engine in the event of a crash.

To provide some forward vision as a precaution against hitting ship masts, trees, or structures while flying at low altitude, a Ryan employee who had served in the submarine service installed a periscope which Lindbergh helped design.

Hall decided that the empennage (tail assembly) and wing control surfaces would not be altered from his original Ryan M-2 design, thus minimizing redesign time that was not available without delaying the flight.

[11] This setup resulted in a negatively stable design that tended to randomly introduce unanticipated pitch, yaw, and bank (roll) elements into its overall flight characteristics.

Also, although he was an airmail pilot, he refused to carry souvenir letters on the transatlantic journey, insisting that every spare ounce be devoted to fuel.

[13] A small, left-facing Indian-style swastika was painted on the inside of the original propeller spinner of the Spirit of St. Louis along with the names of all the Ryan Aircraft employees, including Dapper Dan, who designed and built it.

"[14] Lindbergh subsequently flew the Spirit of St. Louis to Belgium and England before President Calvin Coolidge sent the light cruiser Memphis to bring them back to the United States.

Arriving on June 11, Lindbergh and the Spirit were escorted up the Potomac River to Washington, D.C., by a fleet of warships, multiple flights of military pursuit aircraft, bombers, and the rigid airship Los Angeles (which was itself a veteran of one of the earliest transatlantic flights), where President Coolidge presented the 25-year-old U.S. Army Reserve aviator with the Distinguished Flying Cross.

According to the published log of the Spirit, during his 3-month tour of the US, he allowed Major Thomas Lamphier (Commander of the 1st Pursuit Squadron, Selfridge Field) and Lieutenant Philip R. Love (classmate in flight school and colleague of Lindbergh's in the airmail service of Robertson Aircraft Corporation) to pilot the Spirit of St. Louis for ten minutes each on July 1 and August 8, 1927, respectively.

[17] The Spirit of St. Louis appears today much as it appeared on its accession into the Smithsonian collection in 1928, except that the gold color of the aircraft's aluminum nose panels is an artifact of well-intended early conservation efforts: Not long after the museum took possession of the Spirit, conservators applied a clear layer of varnish or shellac to the forward panels in an attempt to preserve the flags and other artwork painted on the engine cowling.

This was done to preserve the Spirit's original tires which, due to age and lessening of vulcanization, are unable to sustain the aircraft's weight without disintegration (conservation was also likely undertaken on the wheel assembly itself).

[21][23] Pilot Frank Hawks purchased a Mahoney Ryan B-1 Brougham (NC3009) with money from his wife, naming the plane the "Spirit of San Diego.

[28] Through the efforts of both staff and volunteers, the Experimental Aircraft Association in Oshkosh, Wisconsin produced two reproductions of the Spirit of St. Louis, powered by Continental R-670-4 radial engines, the first in 1977 (of which was to be based on a conversion from a B-1 Brougham; the aircraft proved to be too badly deteriorated to be used in that manner), flown by EAA founder Paul Poberezny to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Lindbergh's flight across the Atlantic Ocean and subsequent tour of the United States.

Shortly after takeoff at an air show in Coventry, England, structural failure occurred, resulting in a fatal crash, killing its owner-pilot, Captain Pierre Holländer.

[31] [Note 3][33] A recently completed Spirit reproduction, intended for airworthiness is owned by the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome (ORA), fulfilling a lifelong dream of its primary founder, Cole Palen (1925–1993).

The reproduction project had been started by Cole before his own death and has mostly been subsequently built by former ORA pilot and current vintage aircraft maintenance manager Ken Cassens, receiving its wing covering, completed with doped fabric in 2015.

With the intention of creating a copy of the aircraft "as it sits now," with all the patches, updates or modifications recreated in pains-taking detail and the added bonus of being airworthy Norman completed the project in 2019.

[38][39][40] In 2015, with coordinated efforts by fellow Spirit researcher Ty Sundstrom and the National Air & Space Museum, Norman took detailed measurements to correct errors he had discovered in the existing "Morrow" drawings.

[42] A 90% static reproduction, built in 1956 for The Spirit of St Louis film by studio employees, is now on display at the Wings of the North Air Museum in Eden Prairie, MN.

We don’t know exactly when, but soon after the Smithsonian acquired the Spirit in May 1928, we sought to preserve the markings by applying a clear coat of varnish or shellac.