Spirit of the Dead Watching

Spirit of the Dead Watching (Manao tupapau) is an 1892 oil on burlap canvas painting by Paul Gauguin, depicting a nude Tahitian girl lying on her stomach.

[1][a] The subject of the painting is Gauguin's 13-year-old[3] native "wife" Teha'amana (called Tehura in his letters), who one night, according to Gauguin, was lying in fear when he arrived home late: "immobile, naked, lying face downward flat on the bed with the eyes inordinately large with fear [...] Might she not with my frightened face take me for one of the demons and specters, one of the Tupapaus, with which the legends of her race people sleepless nights?

Mathews says it is too simple to attribute Tehura's terror to her belief in spirits and irrational fear of the dark; she says, following Sweetman,[8] that Gauguin's sexual predilections should not be ignored when trying to understand the work.

[9][10][11] Stephen F. Eisenman, professor of Art History at Northwestern University, suggests the painting and its narrative is "a veritable encyclopaedia of colonial racism and misogyny".

[12][13] Other historians such as Naomi E. Maurer have viewed the narrative as a device to make the indecency of the subject more acceptable to a European audience.

He had seen it exhibited at the 1889 Exposition Universelle and commented in a review, "La Belle Olympia, who once caused such a scandal, is esconced there like the pretty woman she is, and draws not a few appreciative glances".

After the French state purchased Olympia from Manet's widow, with funds from a public subscription organised by Claude Monet, Gauguin took the opportunity to make a three-quarter size copy when it was exhibited in the Musée du Luxembourg.

[17] Claire Frèches-Thory remarks that Olympia, the modern equivalent of Titian's Venus of Urbino, is a constant presence in Gauguin's great nudes of the South Pacific: Spirit of the Dead Watching, Te arii vahine, and Nevermore.

[19][b] She attempts this by concentrating on a detailed reading of a single painting, the Spirit of the Dead Watching, advancing a new theory of avant-gardism as a kind of game-play involving first reference, then deference, and finally difference.

Thus, by formal reference to Manet's Olympia, Gaughin has reintroduced himself, taking his place in the avant-garde as artist, as owner, and as colonist.

[22] There are five sources for Gauguin's description of the painting: a letter to his patron Daniel Monfreid dated 8 December 1892, another letter to his wife Mette the same day, his 1893 manuscript Cahier pour Aline ("Notebook for Aline"), the first unpublished 1893-4 draft of Noa Noa [ca] and then finally the published 1901 version prepared together with his collaborator Charles Morice [fr].

[25] He translates the title Manao tupapau as "Think of the Ghost, or, The Spirits of the Dead are Watching" and goes on to say that he wants to reserve it for a later sale, but will sell for 2,000 francs.

The draperies are chrome 2. because this colour suggests night, without explaining it however, and furthermore serves as a happy medium between the yellow orange and the green, completing the harmony.

Finally, to end, I make the ghost quite simply, a little old woman; because the young girl, unacquainted with the spirits of the French stage, could not visualise death except in the form of a person like herself.

To conclude, the painting had to be made very simple, the motif being savage, childlike [14]According to Gauguin, the phosphorescences that could be seen in Tahiti at night, and which natives believed to be the exhalations of the spirits of the dead, were emitted by mushrooms that grew on trees.

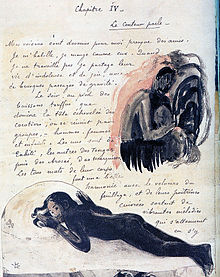

The notebook includes a description of the painting, under the title Genèse d'un tableau ("Genesis of a picture"), accompanied by a watercolor sketch.

[23] It is here that Gauguin remarked the title Manao tupapau can be understood in two ways:[29]In this rather daring position, quite naked on a bed, what might a young Kanaka girl be doing?

To recapitulate: Musical part - undulating horizontal lines - harmonies in orange and blue linked by yellows and violets, from which they derive.

Otherwise the picture is simply a study of a Polynesian nude.Noa Noa was originally conceived as a travelogue to accompany Gauguin's 1893 Durand-Ruel exhibition.

In the draft account, Gauguin describes coming home late to find Teha'amana lying on her bed in the dark.

[34] The description of the painting, previously omitted, now commences:[33][35][36][37]Tehura lay motionless, naked, belly down on the bed: she stared up at me, her eyes wide with fear, and she seemed not to know who I was.

And in the half-shadow, which no doubt seethed with dangerous apparitions and ambiguous shapes, I feared to make the slightest move in case the child should be terrified out of her mind.

...where Morice invokes what Pollock characterizes as an imaginary Utopia whose material foundation nevertheless lay in concrete social spaces, redefined by colonialism.

[33][34] The two accounts of Tehura's reaction, that she was haunted by the tupapau, and that she was angrily suspicious Gauguin had been using prostitutes, likewise pose a similar confrontation between fiction and probable fact.

The narrative may have been inspired by Pierre Loti's novel Madame Chrysanthème, in which the heroine, a geisha girl, is described as being tormented by night frights.

[29] A direct visual inspiration may have come from David Pierre Giottino Humbert de Superville's etching Allegory.

The 1901 La Plume edition was planned to include them, but Gauguin declined to allow the publishers to print them on smooth paper.

Later that same year, when he returned to Paris, it was exhibited at his Durand-Ruel show, where it failed to sell for the 3,000 francs he asked for it, despite favourable reviews from critics including Edgar Dégas.

It was included in his unsuccessful 1895 Hôtel Drouot sale to raise funds for his return to Tahiti, when he was obliged to buy it in for just 900 francs.

Eventually it reached the newly opened Galerie Druet [fr], where it was acquired by Count Kesslar of Weimar, a noted patron of modern art.