Spontaneous symmetry breaking

Notable exceptions include topological phases of matter like the fractional quantum Hall effect.

Typically, when spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs, the observable properties of the system change in multiple ways.

For example the density, compressibility, coefficient of thermal expansion, and specific heat will be expected to change when a liquid becomes a solid.

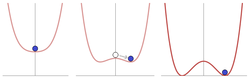

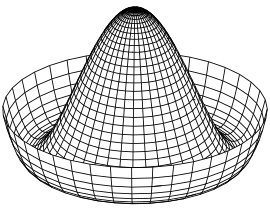

If a ball is put at the very peak of the dome, the system is symmetric with respect to a rotation around the center axis.

But the ball may spontaneously break this symmetry by rolling down the dome into the trough, a point of lowest energy.

[4] In the simplest idealized relativistic model, the spontaneously broken symmetry is summarized through an illustrative scalar field theory.

However, once the system falls into a specific stable vacuum state (amounting to a choice of θ), this symmetry will appear to be lost, or "spontaneously broken".

[8]: 194–195 By the nature of spontaneous symmetry breaking, different portions of the early Universe would break symmetry in different directions, leading to topological defects, such as two-dimensional domain walls, one-dimensional cosmic strings, zero-dimensional monopoles, and/or textures, depending on the relevant homotopy group and the dynamics of the theory.

It served as the prototype and significant ingredient of the Higgs mechanism underlying the electroweak symmetry breaking.

The Weinberg–Salam theory predicts that, at lower energies, this symmetry is broken so that the photon and the massive W and Z bosons emerge.

To overcome this, spontaneous symmetry breaking is augmented by the Higgs mechanism to give these particles mass.

Superconductivity of metals is a condensed-matter analog of the Higgs phenomena, in which a condensate of Cooper pairs of electrons spontaneously breaks the U(1) gauge symmetry associated with light and electromagnetism.

In conventional spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking, there exists an unstable Higgs particle in the theory, which drives the vacuum to a symmetry-broken phase (i.e, electroweak interactions.)

For example, Bardeen, Hill, and Lindner published a paper that attempts to replace the conventional Higgs mechanism in the standard model by a DSB that is driven by a bound state of top-antitop quarks.

Magnets have north and south poles that are oriented in a specific direction, breaking rotational symmetry.

[12] The ferromagnet is the canonical system that spontaneously breaks the continuous symmetry of the spins below the Curie temperature and at h = 0, where h is the external magnetic field.

Spontaneously-symmetry-broken phases of matter are characterized by an order parameter that describes the quantity which breaks the symmetry under consideration.

For symmetry-breaking states, whose order parameter is not a conserved quantity, Nambu–Goldstone modes are typically massless and propagate at a constant velocity.

An important theorem, due to Mermin and Wagner, states that, at finite temperature, thermally activated fluctuations of Nambu–Goldstone modes destroy the long-range order, and prevent spontaneous symmetry breaking in one- and two-dimensional systems.

Similarly, quantum fluctuations of the order parameter prevent most types of continuous symmetry breaking in one-dimensional systems even at zero temperature.

(An important exception is ferromagnets, whose order parameter, magnetization, is an exactly conserved quantity and does not have any quantum fluctuations.)

[13] It was shown, in the presence of a symmetric Hamiltonian, and in the limit of infinite volume, the system spontaneously adopts a chiral configuration — i.e., breaks mirror plane symmetry.

Physicists Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa, of Kyoto University, shared the other half of the prize for discovering the origin of the explicit breaking of CP symmetry in the weak interactions.