Headward erosion

Once a stream has begun to cut back, the erosion is sped up by the steep gradient the water is flowing down.

For example, headward erosion by the Shenandoah River, a tributary of the Potomac River in the U.S. state of Virginia, permitted the Shenandoah to capture successively the original upstream segments of Beaverdam Creek, Gap Run and Goose Creek, three smaller tributaries of the Potomac.

Insequent streams form by random headward erosion, usually from sheetflow of water over the landform surface.

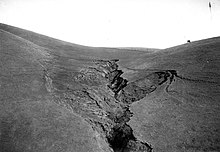

The water collects in channels where the velocity and erosional power increase, cutting into and extending the heads of gullies.

Subsequent streams form by selective headward erosion by cutting away at less resistive rocks in the terrain.