Squatting in the Netherlands

By the 1980s, it had become a powerful anarchist social movement which regularly came into conflict with the state, particularly in Amsterdam with the Vondelstraat and coronation riots.

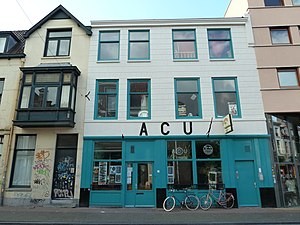

Some squats in cities have successfully legalised into still extant social centres and housing cooperatives such as ACU in Utrecht, the Grote Broek in Nijmegen, the Landbouwbelang in Maastricht, ORKZ in Groningen, the Poortgebouw in Rotterdam and Vrankrijk in Amsterdam.

Their legal justification was based on a 1914 decision by the Supreme Court which ruled that in order to show residential use in a property, all that was needed was a chair, a table and a bed.

[1] Squatting in the Netherlands in its modern form has its origins in the 1960s, when the country was suffering a housing shortage whilst at the same time many properties stood derelict.

[1][3] As well as mobilising the 1914 decision, squatters employed a 1971 Supreme Court ruling that the concept of domestic peace (Dutch: huisvrede) required permission from the current occupant for anybody else to enter a property.

In Amsterdam, the city council bought 200 buildings in the early 1980s, handing them over to housing associations which then made contracts with individual tenants.

[3] The Poortgebouw in Rotterdam was squatted in 1980 and two years later the inhabitants agreed to pay rent to the city council, forming a housing cooperative of 30 people with a bar and alternative venue on the ground floor.

[11] ORKZ, or the Old Roman Catholic Hospital (Dutch: Oude Rooms-Katholieke Ziekenhuis), is located in Groningen on the Verlengde Hereweg.

[13] There are also squats which refused or were unable to legalise such as De Blauwe Aanslag in The Hague, Het Slaakhuis in Rotterdam, ADM in Amsterdam and the Landbouwbelang in Maastricht.

The Landbouwbelang is a former grain silo beside the Meuse (Dutch: Maas) river which houses 15 people and provides space for art exhibitions, music events and various festivals.

The complex, which included a bar, a freeshop, a library meeting rooms and offices for a group supporting illegal migrants, had been negotiating with the city council in order to legalise its activities until the talks stalled in 2008.

The villa was placed on a list of the most endangered monuments in Europe and it was squatted in 2018 by people wanting to prevent further dilapidation.

[20] Squatting in the Netherlands, particularly in Amsterdam, became a rather institutionalised process, although the squatters movement continued to evolve with one development being the occupation of large office buildings by refugee collectives.

In 2016, a report was published by the Dutch Government which stated that between October 2010 and November 2014, 529 people had been arrested for the new crime of squatting, in 213 separate incidents.