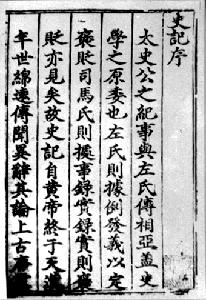

Sima Qian

Although he is universally remembered for the Records, surviving works indicate that he was also a gifted poet and prose writer, and he was instrumental in the creation of the Taichu calendar, which was officially promulgated in 104 BC.

In the postface of the Records, he implicitly compared his universal history of China to the classics of his day, the Guoyu by Zuo Qiuming, "Li Sao" by Qu Yuan, and the Art of War by Sun Bin, pointing out that their authors all suffered great personal misfortunes before their lasting monumental works could come to fruition.

[4] He then went to seek the burial place of the legendary rulers Yu the Great on Mount Xianglu and Shun in the Jiuyi Mountains (modern Ningyuan County, Hunan).

[4] After his travels, Sima was chosen to be a Palace Attendant in the government, whose duties were to inspect different parts of the country with Emperor Wu in 122 BC.

[5] In 96 BC, on his release from prison, Sima chose to live on as a palace eunuch to complete his histories, rather than commit suicide as was expected of a gentleman-scholar who had been disgraced by being castrated.

But the reason I have not refused to bear these ills and have continued to live, dwelling in vileness and disgrace without taking my leave, is that I grieve that I have things in my heart which I have not been able to express fully, and I am shamed to think that after I am gone my writings will not be known to posterity.

[10] Some later historians claimed that Sima Qian himself became implicated in the rebellion as a result of his friendship with Ren An and was executed as part of the purge of the crown prince's supporters in court; however, the earliest-attested record of this account dates from the 4th century.

He and most modern historians believe that Sima Qian spent his last days as a scholar in reclusion (隱士; yǐnshì) after leaving the Han court, perhaps dying around the same time as Emperor Wu in 87/86 BC.

[1] The jizhuanti (紀傳體) format divides a work into several different types of chapters, most prominently 'basic annals' (本紀; benji) and 'ordered biographies' (列傳; liezhuan).

Sima was greatly influenced by Confucius's Spring and Autumn Annals, which on the surface is a succinct chronology from the events of the reigns of the twelve dukes of Lu from 722 to 484 BC.

[5] Many Chinese scholars have and still do view how Confucius ordered his chronology as the ideal example of how history should be written, especially with regards to what he chose to include and to exclude, and his choice of words as indicating moral judgments.

[11] Sima took this view himself as he explained: 夫春秋 ... 別嫌疑,明是非,定猶豫,善善惡惡,賢賢賤不肖,存亡國,繼絕世,補敝起廢。 It [Spring and Autumn Annals] distinguishes what is suspicious and doubtful, clarifies right and wrong, and settles points which are uncertain.

[11] For Sima, the writing of history was no mere antiquarian pursuit, but was rather a vital moral task as the historian would "preserve memory", and thereby ensure the ultimate victory of good over evil.

At the beginning of the Shiji, Sima declared himself a follower of Confucius's approach in the Analects to "hear much but leave to one side that which is doubtful, and speak with due caution concerning the remainder".

[13] In the same way, Sima discounted accounts in the traditional records that were "ridiculous" such as the pretense that Prince Tan could via the use of magic make the clouds rain grain and horses grow horns.

[13] Sima mentioned after one of his trips across China that: "When I had occasion to pass through Feng and Beiyi I questioned the elderly people who were about the place, visited the old home of Xiao He, Cao Can, Fan Kuai and Xiahou Ying, and learned much about the early days.

"[14] Reflecting the traditional Chinese reverence for age, Sima stated that he preferred to interview the elderly as he believed that they were the most likely to supply him with correct and truthful information about what had happened in the past.

[14] Sima's history of 130 chapters began with the legendary Yellow Emperor and extended to his own time, and covered not only China, but also neighboring nations like Korea and Vietnam.

[15] In his comments about the Xiongnu, Sima refrained from evoking claims about the innate moral superiority of the Han over the "northern barbarians" that were the standard rhetorical tropes of Chinese historians in this period.

[18] Sima also broke new ground by using more sources like interviewing witnesses, visiting places where historical occurrences had happened, and examining documents from different regions and/or times.

[14] The last section dealing with biographies covers individuals judged by Sima to have made a major impact on the course of history, regardless of whether they were of noble or humble birth and whether they were born in the central states, the periphery, or barbarian lands.

[14] Unlike traditional Chinese historians, Sima went beyond the androcentric, nobility-focused histories by dealing with the lives of women and men such as poets, bureaucrats, merchants, comedians/jesters, assassins, and philosophers.

[19] Empress Lü and Xiang Yu were the effective rulers of China during reigns Hui of the Han and Yi of Chu, respectively, so Sima placed both their lives in the basic annals.

[19] At the end of most of the chapters, Sima usually wrote a commentary in which he judged how the individual lived up to traditional Chinese values like filial piety, humility, self-discipline, hard work and concern for the less fortunate.

Sima's works were influential to Chinese writing, serving as ideal models for various types of prose within the neo-classical ("renaissance" 复古) movement of the Tang–Song period.

His influence was derived primarily from the following elements of his writing: his skillful depiction of historical characters using details of their speech, conversations, and actions; his innovative use of informal, humorous, and varied language; and the simplicity and conciseness of his style.

At that time, the astrologer had an important role, responsible for interpreting and predicting the course of government according to the influence of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as other astronomical and geological phenomena such as solar eclipses and earthquakes, which depended on revising and upholding an accurate calendar.

They changed their surnames to Tong (同 = 丨+ 司) and Féng (馮 = 仌 + 馬), respectively, to hide their origins while continuing to secretly offer sacrifices to the Sima ancestors.

[29] According to the Book of Han, Wang Mang sent an expedition to search for and ennoble a male-line descent of Sima Qian as 史通子 ("Viscount of Historical Mastery"), although it was not recorded who received this title of nobility.

A Qing dynasty stele 重修太史廟記 (Records of the Renovation of the Temple of the Grand Historian) erected in the nearby county seat Han City (韓城) claims that the title was given to the grandson of Sima Lin.