Saint Boniface

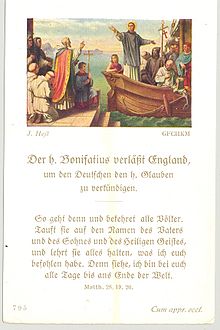

Boniface (born Wynfreth; c. 675[2] – 5 June 754) was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of Francia during the eighth century.

Norman Cantor notes the three roles Boniface played that made him "one of the truly outstanding creators of the first Europe, as the apostle of Germania, the reformer of the Frankish church, and the chief fomentor of the alliance between the papacy and the Carolingian family.

He received further theological training in the Benedictine monastery and minster of Nhutscelle (Nursling),[16] not far from Winchester, which under the direction of abbot Winbert had grown into an industrious centre of learning in the tradition of Aldhelm.

[17] Winfrid taught in the abbey school and at the age of 30 became a priest; in this time, he wrote a Latin grammar, the Ars Grammatica, besides a treatise on verse and some Aldhelm-inspired riddles.

[19] Around 716, when his abbot Wynberth of Nursling died, he was invited (or expected) to assume his position—it is possible that they were related, and the practice of hereditary right among the early Anglo-Saxons would affirm this.

He spent a year with Willibrord, preaching in the countryside, but their efforts were frustrated by the war then being carried on between Charles Martel and Radbod, King of the Frisians.

Lutz von Padberg and others claim that what the vitae leave out is that the action was most likely well-prepared and widely publicized in advance for maximum effect, and that Boniface had little reason to fear for his personal safety since the Frankish fortified settlement of Büraburg was nearby.

The initial grant for the abbey was signed by Carloman, the son of Charles Martel, and a supporter of Boniface's reform efforts in the Frankish church.

Boniface himself explained to his old friend, Daniel of Winchester, that without the protection of Charles Martel he could "neither administer his church, defend his clergy, nor prevent idolatry".

According to German historian Gunther Wolf, the high point of Boniface's career was the Concilium Germanicum, organized by Carloman in an unknown location in April 743.

[30] By appointing his own followers as bishops, he was able to retain some independence from the Carolingians, who most likely were content to give him leeway as long as Christianity was imposed on the Saxons and other Germanic tribes.

Of those three books, the Ragyndrudis Codex shows incisions that could have been made by sword or axe; its story appears confirmed in the Utrecht hagiography, the Vita altera, which reports that an eye-witness saw that the saint at the moment of death held up a gospel as spiritual protection.

There is good reason to believe that the Gospel he held up was the Codex Sangallensis 56, which shows damage to the upper margin, which has been cut back as a form of repair.

The UK National Shrine is located at the Catholic church at Crediton, Devon, which has a bas-relief of the felling of Thor's Oak, by sculptor Kenneth Carter.

There are quite a few churches dedicated to St. Boniface in the United Kingdom: Bunbury, Cheshire; Chandler's Ford and Southampton Hampshire; Adler Street, London; Papa Westray, Orkney; St Budeaux, Plymouth (now demolished); Bonchurch, Isle of Wight; Cullompton, Devon.

In 1818, Father Norbert Provencher founded a mission on the east bank of the Red River in what was then Rupert's Land, building a log church and naming it after St. Boniface.

It is dated between 917 (Radboud's death) and 1075, the year Adam of Bremen wrote his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, which used the Vita tertia.

Boniface engaged in regular correspondence with fellow churchmen all over Western Europe, including the three popes he worked with, and with some of his kinsmen back in England.

They were assembled by order of archbishop Lullus, Boniface's successor in Mainz, and were initially organized into two parts, a section containing the papal correspondence and another with his private letters.

[52] Stephan Alexander Würdtwein's 1789 edition, Epistolae S. Bonifacii Archiepiscopi Magontini, was the basis for a number of (partial) translations in the nineteenth century.

The first version to be published by Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) was the edition by Ernst Dümmler (1892); the most authoritative version until today is Michael Tangl's 1912 Die Briefe des Heiligen Bonifatius, Nach der Ausgabe in den Monumenta Germaniae Historica, published by MGH in 1916.

[51] This edition is the basis of Ephraim Emerton's selection and translation in English, The Letters of Saint Boniface, first published in New York in 1940; it was republished most recently with a new introduction by Thomas F.X.

Helmut Gneuss reports that one manuscript copy of the treatise originates from (the south of) England, mid-eighth century; it is now held in Marburg, in the Hessisches Staatsarchiv.

[55] He also wrote a treatise on verse, the Caesurae uersuum, and a collection of twenty acrostic riddles, the Enigmata, influenced greatly by Aldhelm and containing many references to works of Vergil (the Aeneid, the Georgics, and the Eclogues).

[57] Three octosyllabic poems written in clearly Aldhelmian fashion (according to Andy Orchard) are preserved in his correspondence, all composed before he left for the continent.

The second part of the 19th century saw increased tension between Catholics and Protestants; for the latter, Martin Luther had become the model German, the founder of the modern nation, and he and Boniface were in direct competition for the honor.

Especially in Germany, these celebrations had a distinctly political note to them and often stressed Boniface as a kind of founder of Europe, such as when Konrad Adenauer, the (Catholic) German chancellor, addressed a crowd of 60,000 in Fulda, celebrating the feast day of the saint in a European context: Das, was wir in Europa gemeinsam haben, [ist] gemeinsamen Ursprungs ("What we have in common in Europe comes from the same source").

The pope next celebrated mass outside the cathedral, in front of an estimated crowd of 100,000, and hailed the importance of Boniface for German Christianity: Der heilige Bonifatius, Bischof und Märtyrer, 'bedeutet' den 'Anfang' des Evangeliums und der Kirche in Eurem Land ("The holy Boniface, bishop and martyr, 'signifies' the beginning of the gospel and the church in your country").

biographies (for instance, by Auke Jelsma in Dutch, Lutz von Padberg in German, and Klaas Bruinsma in Frisian), and a fictional completion of the Boniface correspondence (Lutterbach, Mit Axt und Evangelium).

[69] In the modern era, Lutz von Padberg published a number of biographies and articles on the saint focusing on his missionary praxis and his relics.