St. Francis Dam

The dam failed catastrophically in 1928, killing at least 431 people in the subsequent flood,[2][3] in what is considered to have been one of the worst American civil engineering disasters of the 20th century and the third-greatest loss of life in California history.

He felt that there should be a reservoir of sufficient size to provide water for Los Angeles for an extended period in the event of a drought or if the aqueduct were damaged by an earthquake.

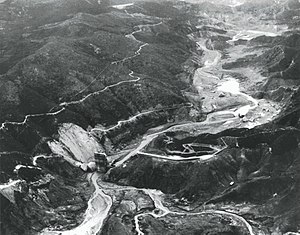

2 were to be built, with what he perceived as favorable topography, a natural narrowing of the canyon downstream of a wide, upstream platform which would allow the creation of a large reservoir area with a minimum possible dam.

In the area where the dam would later be situated, Mulholland found the mid- and upper portion of the western hillside consisted mainly of a reddish-colored conglomerate and sandstone formation that had small veins of gypsum interspersed within it.

Below the red conglomerate, down the remaining portion of the western hillside, crossing the canyon floor and up the eastern wall, a drastically different rock composition prevailed.

Later, although many geologists disagreed on the exact location of the area of contact between the two formations, a majority opinion placed it at the inactive San Francisquito Fault line.

Although Mulholland wrote of the unstable nature of the face of schist on the eastern side of the canyon in his annual report to the Board of Public Works in 1911,[15] this fact was either misjudged or ignored by Stanley Dunham, the construction supervisor of the St. Francis Dam.

Dunham testified, at the coroner's inquest, that tests which he had ordered yielded results which showed the rock to be hard and of the same nature throughout the entire area which became the eastern abutment.

Originally, the planned site of this new large reservoir was to be in Big Tujunga Canyon, above the community now known as Sunland, in the northeast portion of the San Fernando Valley, but the high asking prices of the ranches and private land which had to be acquired were, in Mulholland's view, an attempted hold-up of the city.

The Los Angeles Aqueduct had become the target of frequent sabotage by angry farmers and landowners in the Owens Valley and the city was eager to avoid any repeat of these expensive and time-consuming repairs.

[22][23] Annually, as did most other city entities, the Bureau of Water Works and Supply and the ancillary departments reported to the Board of Public Service Commissioners on the prior fiscal year's activities.

[24][25] On July 1, 1924, the same day Mulholland was to submit his annual report to the Board of Public Service Commissioners, Office Engineer W. W. Hurlbut informed him that all of the preliminary work on the dam had been completed.

[28][29]This 10-foot (3.0 m) increase in the dam's height over the original plan of 1923 necessitated the construction of a 588-foot (179 m) long wing dike along the top of the ridge adjacent to the western abutment in order to contain the enlarged reservoir.

Mulholland, along with his Assistant Chief Engineer and General Manager Harvey Van Norman, inspected the cracks and judged them to be within expectation for a concrete dam the size of the St. Francis.

At the same time, another fracture appeared in a corresponding position on the eastern portion of the dam, starting at the crest near the last spillway section and running downward at an angle for sixty-five feet before ending at the hillside.

Concerned not only because other leaks had appeared in this same area in the past but more so that the muddy color of the runoff he observed could indicate the water was eroding the foundation of the dam, he immediately alerted Mulholland.

1, there was a sharp voltage drop at 11:57:30 p.m.[49] Simultaneously, a transformer at Southern California Edison's (SCE) Saugus substation exploded, a situation investigators later determined was caused by wires up the western hillside of San Francisquito Canyon about ninety feet above the dam's east abutment shorting.

Power was quickly restored via tie-lines with SCE, but as the floodwater entered the Santa Clara riverbed it overflowed the river's banks, flooding parts of present-day Valencia and Newhall.

In a statement, Mulholland said, "I would not venture at this time to express a positive opinion as to the cause of the St. Francis Dam disaster... Mr. Van Norman and I arrived at the scene of the break around 2:30 a.m. this morning.

Although this may have been sufficient time to answer what they had been directed to determine, they had been deprived of the sworn testimony at the coroner's inquest, which was scheduled to be convened March 21, the only inquiry that took into consideration factors other than geology and engineering.

Although the water and electricity from the project were needed, the idea of the construction of such a massive dam of similar design, which would create a reservoir seven hundred times larger than the St. Francis, did not sit well with many in light of the recent disaster and the devastation.

Inspection galleries, pressure grouting, drainage wells and deep cut-off walls are commonly used to prevent or remove percolation, but it is improbable that any or all of these devices would have been adequately effective, though they would have ameliorated the conditions and postponed the final failure.

"The west end," the commission stated, "was founded upon a reddish conglomerate which, even when dry, was of decidedly inferior strength and which, when wet, became so soft that most of it lost almost all rock characteristics."

The prevailing thought was that increasing water percolation through the fault line had either undermined or weakened the foundation to a point that a portion of the structure blew out or the dam collapsed from its own immense weight.

This chart clearly showed that there had been no significant change in the reservoir level until forty minutes before the dam's failure, at which time a small though gradually increasing loss was recorded.

"[71] Willis and the Grunskys agreed with the other engineers and investigators about the poor quality and deteriorating conditions of the entire foundation, although they maintained that a critical situation developed on the east abutment.

Due for the most part to inadequate drainage of the base and side abutments, the phenomenon of uplift destabilizes gravity dams by reducing the structure's "effective weight", making it less able to resist horizontal water pressure.

[71] Although this investigation was insightful and informative, the theory, along with others which hypothesized an appreciably increasing amount of seepage just prior to the failure, becomes less likely when it is compared against the eyewitness accounts of the conditions in the canyon and near the dam during the last thirty minutes before its collapse.

Indeed, the site had been inspected twice, at different times, by two of the leading geologists and civil engineers of the day, Grunsky and John C. Branner of Stanford University; neither found fault with the San Francisquito rock.

Over 450 lives were lost in this, one of California's greatest disasters.San Francisquito Canyon Road sustained heavy storm damage in 2005, and when rebuilt in 2009 it was re-routed away from the original roadbed and the remains of the main section of the dam.