Saint Patrick

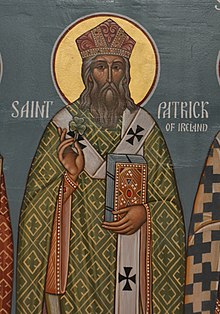

Saint Patrick (Latin: Patricius; Irish: Pádraig [ˈpˠɑːɾˠɪɟ] or [ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ]; Welsh: Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland.

Tírechán's seventh-century Collectanea gives: "Magonus, that is, famous; Succetus, that is, god of war; Patricius, that is, father of the citizens; Cothirthiacus, because he served four houses of druids.

[12] "Succetus", which also appears in Muirchú moccu Machtheni's seventh-century Life as Sochet,[12] is identified by Mac Neill as "a word of British origin meaning swineherd".

[13] Cothirthiacus also appears as Cothraige in the 8th-century biographical poem known as Fiacc's Hymn and a variety of other spellings elsewhere, and is taken to represent a Primitive Irish: *Qatrikias, although this is disputed.

Supporting the later date, the annals record that in 553 "the relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a shrine by Colum Cille" (emphasis added).

[28] In 1926 Eoin MacNeill also advanced a claim for Glamorgan in south Wales,[29] possibly the village of Banwen, in the Upper Dulais Valley, which was the location of a Roman marching camp.

[30] Patrick's father, Calpurnius, is described as a decurion (Senator and tax collector) of an unspecified Romano-British city, and as a deacon; his grandfather Potitus was a priest from Bonaven Tabernia.

Hood suggests that the Victoricus of St. Patrick's vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396.

[44] Bury suggests that Wicklow was also the port through which Patrick made his escape after his six years' captivity, though he offers only circumstantial evidence to support this.

Tírechán writes, "I found four names for Patrick written in the book of Ultán, bishop of the tribe of Conchobar: holy Magonus (that is, "famous"); Succetus (that is, the god of war); Patricius (that is, father of the citizens); Cothirtiacus (because he served four houses of druids).

[67] The Patrick portrayed by Tírechán and Muirchu is a martial figure, who contests with druids, overthrows pagan idols, and curses kings and kingdoms.

However, the emphasis Tírechán and Muirchu placed on female converts, and in particular royal and noble women who became nuns, is thought to be a genuine insight into Patrick's work of conversion.

Tírechán's account suggests that many early Patrician churches were combined with nunneries founded by Patrick's noble female converts.

It may be doubted whether such accounts are an accurate representation of Patrick's time, although such violent events may well have occurred as Christians gained in strength and numbers.

[75][76] In pagan Ireland, three was a significant number and the Irish had many triple deities, a fact that may have aided Patrick in his evangelisation efforts when he "held up a shamrock and discoursed on the Christian Trinity".

[83] Tírechán wrote in the 7th century that Patrick spent forty days on the mountaintop of Cruachán Aigle, as Moses did on Mount Sinai.

Patrick ended his fast when God gave him the right to judge all the Irish at the Last Judgement, and agreed to spare the land of Ireland from the final desolation.

Muirchú writes that a pagan chieftain named Dáire would not let Patrick build a church on the hill of Ard Mhacha, but instead gave him lower ground to the east.

[89] The twelfth-century work Acallam na Senórach tells of Patrick being met by two ancient warriors, Caílte mac Rónáin and Oisín, during his evangelical travels.

The heroic pagan lifestyle of the warriors, of fighting and feasting and living close to nature, is contrasted with the more peaceful, but unheroic and non-sensual life offered by Christianity.

[92] According to the Annals of the Four Masters, an early-modern compilation of earlier annals, his corpse soon became an object of conflict in the Battle for the Body of Saint Patrick (Cath Coirp Naomh Padraic): The Uí Néill and the Airgíalla attempted to bring it to Armagh; the Ulaid tried to keep it for themselves.When the Uí Néill and the Airgíalla came to a certain water, the river swelled against them so that they were not able to cross it.

The appointment of Palladius and his fellow bishops was not obviously a mission to convert the Irish, but more probably intended to minister to existing Christian communities in Ireland.

[124] Thomas Dinely, an English traveller in Ireland in 1681, remarked that "the Irish of all stations and condicõns were crosses in their hatts, some of pins, some of green ribbon.

"[125] Jonathan Swift, writing to "Stella" of Saint Patrick's Day 1713, said "the Mall was so full of crosses that I thought all the world was Irish".

[129] The Irish Times in 1935 reported they were still sold in poorer parts of Dublin, but fewer than those of previous years "some in velvet or embroidered silk or poplin, with the gold paper cross entwined with shamrocks and ribbons".

[130] The National Museum of Ireland in Dublin possesses a bell (Clog Phádraig)[131][133] first mentioned, according to the Annals of Ulster, in the Book of Cuanu in the year 552.

The folklorist Jenny Butler discusses how these traditions have been given new layers of meaning over time while also becoming tied to Irish identity both in Ireland and abroad.

The symbolic resonance of the Saint Patrick figure is complex and multifaceted, stretching from that of Christianity's arrival in Ireland to an identity that encompasses everything Irish.

There is also evidence of a combination of indigenous religious traditions with that of Christianity, which places St Patrick in the wider framework of cultural hybridity.

Saint Patrick's Day celebrations include many traditions that are known to be relatively recent historically but have endured through time because of their association either with religious or national identity.