Chad of Mercia

He features strongly in the work of the Venerable Bede and is credited, together with Bishop Wilfrid of Ripon, with introducing Christianity to the Mercian kingdom.

The only major fact that Bede gives about Chad's early life is that he was a student of Aidan at the Celtic monastery at Lindisfarne.

Chad was trained in an entirely distinct monastic tradition that tended to look back to Martin of Tours as an exemplar.

[11] The Irish and early Anglo-Saxon monasticism experienced by Chad was peripatetic, stressed ascetic practices and had a strong focus on Biblical exegesis, which generated a profound eschatological consciousness.

It was on the initiative of Cælin that Ethelwald donated land for the building of a monastery at Lastingham near Pickering in the North York Moors, close to one of the still-usable Roman roads.

[13] Chad's first appearance as an ecclesiastical prelate occurs in 664, shortly after the Synod of Whitby, when many Church leaders had been wiped out by the plague – among them Cedd, who died that year at Lastingham.

Owin was a household official of Æthelthryth, an East Anglian princess who had come to marry Ecgfrith, Oswiu's younger son.

The typically Celtic Christian involvement with nature was not like the modern romantic preoccupation but a determination to read in it the mind of God, particularly in relation to the last things.

However, the growing importance of his family within the Northumbrian state is clear from Bede's account of Cedd's career of the founding of their monastery at Lastingham in North Yorkshire.

[5] This concentration of ecclesiastical power and influence within the network of a noble family was probably common in Anglo-Saxon England: an obvious parallel would be the children of King Merewalh in Mercia in the following generation.

Probably as a newly ordained priest, he was sent in 653 by Oswiu on a difficult mission to the Middle Angles, at the request of their sub-king Peada, part of a developing pattern of Northumbrian intervention in Mercian affairs.

This was one of several outbreaks of the plague; they badly hit the ranks of the Church leadership, with most of the bishops in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms dead, including the archbishop of Canterbury.

York later became the diocesan city partly because it had already been designated as such in the earlier Roman-sponsored mission of Paulinus to Deira, so it is not clear whether Bede is simply echoing the practice of his own day, or whether Oswiu and Chad were considering a territorial basis and a see for his episcopate.

The most obvious reason for Chad's tortuous travels would be that he was also on a diplomatic mission from Oswiu, seeking to build an encircling alliance around Mercia, which was rapidly recovering from its position of weakness.

Bede points out that "at that time there was no other bishop in all Britain canonically ordained except Wini" and the latter had been installed irregularly by the king of the West Saxons.

Basic Christian rites of passage, baptism and confirmation, were almost always performed by a bishop, and for decades to come they were generally carried out in mass ceremonies, probably with little systematic instruction or counselling.

Bede tells us that the net effect of his efforts on the Church was that the Irish monks who still lived in Northumbria either came fully into line with Catholic practices or left for home.

Nevertheless, Bede cannot conceal that Oswiu and Chad had broken significantly with Roman practice in many ways and that the Church in Northumbria had been divided by the ordination of rival bishops.

It was their sub-king, Peada, who had secured the services of Chad's brother Cedd in 653, and they were frequently considered separately from the Mercians proper, a people who lived further to the west and north.

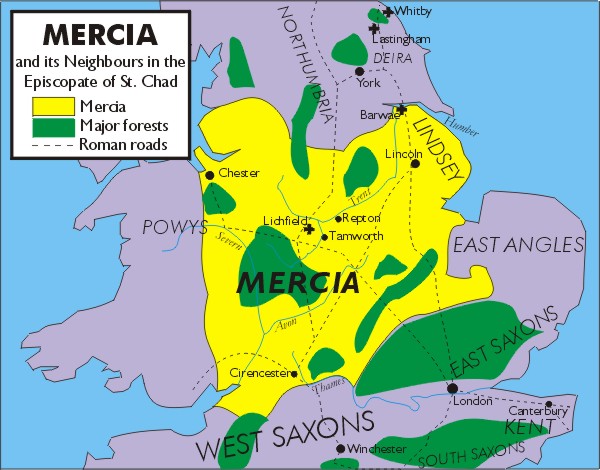

Bede tells us that Chad governed the bishopric of the Mercians and of the people of Lindsey 'in the manner of the ancient fathers and in great perfection of life'.

However, Bede gives little concrete information about the work of Chad in Mercia, implying that in style and substance it was a continuation of what he had done in Northumbria.

Bede does tell us that Chad built for himself a small house at Lichfield, a short distance from the church, sufficient to hold his core of seven or eight brothers, who gathered to pray and study with him there when he was not out on business.

Chad told him that he must keep it to himself for the time being: angels had come to call him to his heavenly reward, and in seven days they would return to fetch him.

Primarily he was a monastic leader, deeply involved in the fairly small communities of loyal brothers who formed his mission team.

The cult had twin foci: his tomb in the nave and more particularly his skull, kept in a special Head Chapel, alongside the south choir aisle.

When his chapel was cleared after his death, his chaplain, Fr Benjamin Hulme, discovered the box containing the relics, which were examined and presented to Bishop Thomas Walsh, the Roman Catholic Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District in 1837 and were enshrined in the new St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham, opened in 1841, in a new ark designed by Augustus Pugin.

They were examined by the Oxford Archaeological Laboratory by carbon-dating techniques in 1985, and all but one of the bones (which was a third femur, and therefore could not have come from Bishop Chad) were dated to the seventh century, and were authenticated as 'true relics' by the Vatican authorities.

In November 2022, one bone relic was returned to Lichfield Cathedral and is housed in a new shrine in the retrochoir and close to where they were located in medieval times.

The Anglican Lichfield Cathedral, at the site of his burial, is dedicated to Chad, and St Mary, and still has a head chapel, where the skull of the saint was kept until it was lost during the Reformation.

[29] Chadkirk Chapel in Romiley, Greater Manchester, may have been dedicated to St Chad; as Kenneth Cameron points out, -kirk ("church") toponyms incorporate the name of the dedicatee more often than that of the patron.