St Cuthbert Gospel

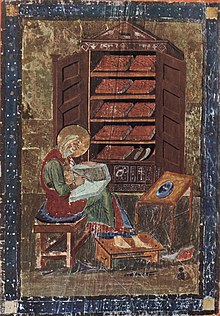

[2] A miniature in the Codex Amiatinus, of the Prophet Ezra writing in his library, shows several books similarly bound in red decorated with geometric designs.

[5] Of treasure bindings from this period, only the lower cover of the Lindau Gospels (750–800, Morgan Library) now survives complete, though there are several references to them, most famously to that of the Book of Kells, which was lost after a theft in 1007.

[23] At the same time, an analysis by Robert Stevick suggests that the designs for both covers were intended to follow a sophisticated geometric scheme of compass and straightedge constructions using the "two true measures of geometry", the ratio between Pythagoras' constant and one, and the golden section.

[24] Although it seems clear from the style of the script that the text was written at Monkwearmouth–Jarrow, it is possible that the binding was then added at Lindisfarne; the form of the plant scrolls can be compared to those on the portable altar also found in Cuthbert's coffin, presumed to have been made there, though also to other works of the period, such as the shaft of an Anglo-Saxon cross from Penrith and the Vespasian Psalter.

The central field contains a plant motif representing a stylised chalice in the centre with a bud and scrolling vine stems leading from it, fruit and several small leaves.

[27] One face of the fragmentary silver cover of the portable altar also recovered from Cuthbert's coffin has a similar combination of elements, with both areas of interlace and, in the four corners, a simple plant motif with a central bud or leaf and a spiral shoot on either side.

[32] It was suggested by Berthe van Regemorter that in the St Cuthbert Gospel this design represents Christ (as the central bud) and the Four Evangelists as the grapes, following John 15:5, "I am the vine, ye are the branches", but this idea has been treated with caution by other scholars.

[34] The lowest horizontal raised line is not straight, being higher at the left, probably because of an error in the marking or drilling of the holes in the cover board through which the ends of the cord run.

[35] The simple twist or chain border in yellow between the two raised frames resembles an element in an initial in the Durham Gospel Book Fragment, an important earlier manuscript from Lindisfarne.

[40] The raised framing lines can be seen from the rear of the front cover to have been produced by gluing cord to the board and tooling the leather over it, in a technique of Coptic origin, of which few early examples survive – one of the closest is a 9th- or 10th-century Islamic binding found in the Mosque of Uqba in Kairouan, Tunisia.

The first appearance of the cords or supports that these "unsupported" bindings lack is found in two other books at Fulda, and they soon became universal in, and characteristic of, Western bookbinding until the arrival of modern machine techniques.

The Northumbrian scribes "imitate very closely the best Italian manuscripts of about the sixth century",[51] but introduced small elements that gave their script a distinct style, which has always been greatly admired.

Illustrations from British Library MS Yates Thompson 26, a manuscript of Bede's prose life of Cuthbert, written c. 721, copied at the priory of Durham Cathedral in the last quarter of the 12th century.

[58] Cuthbert was an Anglo-Saxon, perhaps of a noble family, born in the Kingdom of Northumbria in the mid-630s, some ten years after the conversion of King Edwin to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by that of the rest of his people.

Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome, but his successor Oswald also invited Irish monks from Iona to found the monastery at Lindisfarne where Cuthbert was to spend much of his life.

[60] The earliest biographies concentrate on the many miracles that accompanied even his early life, but he was evidently indefatigable as a travelling priest spreading the Christian message to remote villages, and also well able to impress royalty and nobility.

Thereafter, the royal house of Wessex, who became the kings of England, made a point of devotion to Cuthbert, which also had a useful political message, as they came from opposite ends of the united English kingdom.

Cuthbert was "a figure of reconciliation and a rallying point for the reformed identity of Northumbria and England" after the absorption of the Danish populations into Anglo-Saxon society, according to Michelle Brown.

In 875 the Danish leader Halfdene (Halfdan Ragnarsson), who shared with his brother Ivar the Boneless the leadership of the Great Heathen Army that had conquered much of the south of England, moved north to spend the winter there, as a prelude to settlement and further conquest.

[71] It was possibly at this point that a shelf or inner cover was inserted some way under the lid of Cuthbert's coffin, supported on three wooden bars across the width, and probably with two iron rings fixed to it for lifting it off.

Other bones taken by the party were those remains of St Aidan (d. 651), the founder of the community, that had not been sent to Melrose, and the head of the king and saint Oswald of Northumbria, who had converted the kingdom and encouraged the founding of Lindisfarne.

Then they left the more remote west side of the country and returned to the east, finding a resting-place at Craike near Easingwold, close to the coast, well south of Lindisfarne, but also sufficiently far north of the new Viking kingdom being established at York.

After three or four months it was felt safe to return, and the party had nearly reached Chester-le-Street when their wagon became definitively stuck close to Durham, then a place with cultivated fields, but hardly a settlement, perhaps just an isolated farm.

[75] The account in "Miracle 20" adds that Bishop Flambard, during his sermon on the day the new shrine received Cuthbert's body, showed the congregation "a Gospel of Saint John in miraculously perfect condition, which had a satchel-like container of red leather with a badly frayed sling made of silken threads".

[77] As far as is known the book remained at Durham for the remainder of the Middle Ages, until the Dissolution, kept as a relic in three bags of red leather, normally resting in a reliquary, and there are various records of it being shown to visitors, the more distinguished of which were allowed to hang it round their neck for a while.

According to Reginald of Durham (d. c. 1190) "anyone approaching it should wash, fast and dress in an alb before touching it", and he recorded that a scribe called John who failed to do this during a visit by the Archbishop of York in 1153–54, and "held it with unwashed hands after eating was struck down with a chill".

[84] According to an 18th-century Latin inscription pasted to the inside cover of the manuscript, the St Cuthbert Gospel was given by the 3rd Earl of Lichfield (1718–1772) to the Jesuit priest Thomas Phillips S.J.

[94] The second came in 1969, when T.J. (Julian) Brown, Professor of Palaeography at King's College, London, published a monograph on the St Cuthbert Gospel with another chapter by Powell, who had altered his views in minor respects.

[101] There was a long and somewhat controversial tradition of using manuscripts of the Gospel of John, or extracts such as the opening verse, as a protective or healing amulet or charm, which was especially strong in early medieval Britain and Ireland.

[102] Disapproving references to such uses can be found in the writings of Saints Jerome and Eligius, and Alcuin, but they are accepted by John Chrysostom, Augustine, who "expresses qualified approval" of using manuscripts as a cure for headaches, and Gregory the Great, who sent one to Queen Theodelinda for her son.