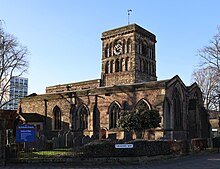

St Nicholas Church, Leicester

Present archeology suggests the site was most likely a courtyard between two gymnasia and that the Jewry Wall was the entrance into the adjacent bath complex which today lies exposed by archeologists to the west of the churchyard.

Ratae's Forum lay immediately to the east of the church and vestiges of masonry from its colonnade still litter St Nicholas' churchyard today.

The abundance of readily available second hand building materials, the prestige of the sites Romanitas, and the central location in the settlement were probably the reason it was selected by the Anglo-Saxons for constructing a church.

[2][1] St Margaret's, located in a Roman cemetery outside the north east corner of the city walls, also has Anglo-Saxon foundations and has been suggested as a candidate for the cathedral however this is not the consensus.

The basilical structure thus took on the form of a cross with the altar probably sitting in a reconstructed apse behind the eastern arch of the tower on the site of the present chancel.

[1] These developments probable followed the 918 reconquest of Leicester by Anglo-Saxon forces under Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, and Edward the Elder, both children of Alfred the Great.

[4] It is probable that either the nave or churchyard, or both depending on weather, were the meeting place of the Jurats of the Moot of Burgesses, the central committee of the government of the ancient borough of Leicester.

At the time of the Doomsday Survey the advowson of St Nicholas was in the possession of either the Bishop of Lincoln or the Lord of Leicester, Hugh de Grandmesnil.

[1] The new dedication, Nicholas of Smyrna, the patron of sailors, merchants, and pawn brokers, was likely chosen because of the proximity of the Soar river port just west of the church and the parish's vibrant commercial life.

After the reform of the chantries this chapel was demolished and has never been reconstructed leaving remnants of the piscina of exposed on the external north wall of the chancel.

For St Nicholas the first consequences of this process were felt in 1538 during the Dissolution of the Monasteries when the nearby monastic houses of Austinfriars, Blackfriars, Greyfriars and the parish's patron, Leicester Abbey, were forcibly suppressed.

The Catholic Restoration did not outlive Mary I and the reforms of Henry and Edward reinstated with a revised Book of Common Prayer under Elizabeth I as part of the Elizabethan Settlement.

The Elizabethan Settlement remained in place until the time of the English Civil War at which point the Church of England was reformed to its most austere extent when the Directory for Public Worship was promulgated by parliament, until the return of definitive edition Book of Common Prayer in 1663 under Charles II.

An old rumour suggests that during the period of the Commonwealth St Nicholas was the one church in the city that refused to obey the rebel parliament and maintained liturgy according to Charles I's Prayer Book.

[5][3] The most notable of the recycled Roman objects in the church is the St Nicholas "paw print tile" visible in the north wall of the Lady Chapel.

It is large section of Roman roof tile with an exceptionally clear paw print of a small dog, presumably made by a straying canine during the drying process.

The romanesque stylistic unity was modified by the replacement of the original sanctuary and the addition of the Lady Chapel in the south aisle during the 13th century, both in an Early English style.

In the 1820s the nave was severely damaged by the removal of its Anglo-Saxon south wall and its replacement with a single bay in a similar form to a railway arch.

The structure was completed in the late Victorian period by the addition of the north aisle and transept with its bricked arch anticipating an unbuilt replacement to the chantry chapel.

The east end is formed two gables of equal height facing the north entrance to the Vaughan Way Underpass, the exterior of the Lady chapel and chancel.

The south elevation is punctuated by a humble 15th-century timber porch, four gothic windows with 19th-century restored reticulated tracery, a small priests door, and an 18th-century slate sundial.

Of the visible areas of the exterior, only the lower levels of the tower hint at the Anglo-Saxon origin of the church with their herringbone pattern of Roman bricks and rustic blind arcading.

[5][3] The crossing tower dates to the 10th century, a time when the church was expanded to include transepts and aisles, and was probably constructed on the site of an earlier apse.

Consisting of four solid piers supporting large triumphal arches the walls both inside and out are decorated with blind arcade work forming three levels, one visible within and two from without.

A key characteristically Anglo-Saxon feature is the herringbone brickwork visible from the external south elevation and inside the locked lower tower chamber.

The sedilia, three adjacent niches set into the south wall of the Lady Chapel, were the seats of the priest and his two assisting deacons during the celebration of solemn masses.

Constructed in the 1875-84 renovation from granite they provide an important view of the nave arcade and a home for the lavatory, sacristy, Sunday school, and tea making facilities.

Either side of him are St George to the left, a Roman soldier and the chief patron saint of England, and the Archangel Michael to the right, depicted bearing the sword of truth and the shield of justice.

[5] The east window of the Lady Chapel in the wall behind the altar was erected in 1929 and depicts the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, including the figures of the Virgin Mary, St Joseph, and Simeon.

The scene is set in the Temple at Jerusalem and an interesting feature are the two caged turtle doves in Joseph's hand, the sacrifice offered by poorer families in thanksgiving for a firstborn child.