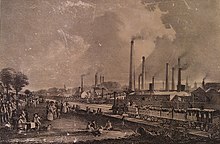

St Rollox Chemical Works

[3] In 1787, Tennant attended a demonstration of Claude Louis Berthollet's chlorine bleaching process that was held by Watt in Birmingham.

2209 on 23 January 1798 for the manufacture of a bleaching liquor by passing chlorine into a well-agitated mixture of lime and water.

The second partner was Alexander Dunlop (his brother married Charles' eldest daughter), who served as accountant to the group.

[3] At the time, sulfuric acid cost £60 per ton and large quantities were needed in the production of chlorine, so Tennant started producing it.

[14] This was further increased by six in 1811, taking the total number to 32 and were much larger, measuring 60 x 14 x 12 feet high, arranged in sets of two or three.

[14][16] In 1825, when the salt tax was removed, the factory moved to producing crystal and ash soda using the Leblanc process.

[3] The process to create alkalis was to add sulfuric acid to salt that produced sodium sulfate, known as saltcake.

The cake was roasted in a vessel by furnace and lime and coal to produce sodium carbonate (soda ash) that was immersed in water for 12 hours.

She considers this wholly arises from the manufacture of vitriol – and if Mr Tennant would give that up, she would let him carry on the other thing as he pleased".

[17] When John Tennant became head of the plant in 1838, the problem of pollution in the form of noxious fumes was foremost in his mind, due to the continual complaints of tainted air from people living in the area.

While in church one Sunday he had the idea of building an exceptionally tall chimney that would take the fumes higher.

McIntyre was initially hesitant, thinking the proposition was a joke, but eventually provided an estimate of works which was accepted.

[19] For more than 50 years the waste piles behind the factory had been accumulating on an old peat bog that lay within a natural basin of sandstone.

[22] The compounds in the waste were lixiviated by rainfall and water from numerous springs in the area enabling a flow to be created out of the bog, described as a "yellow liquor" which consisted of a complex sulfide of calcium.

[22] In 1871, James MacTear, who was the manager at St Rollox, created a chemical process to recover sulfur from the waste piles behind the factory.

[24] The process was reliable, resulting in a product that was cheap to produce and was widely used by manufactures, even though it recovered only 27% to 30% of the available sulfur.