Standardization

Divergent national standards impose costs on consumers and can be a form of non-tariff trade barrier.

[6] Uniform units of length were used in the planning of towns such as Lothal, Surkotada, Kalibangan, Dolavira, Harappa, and Mohenjo-daro.

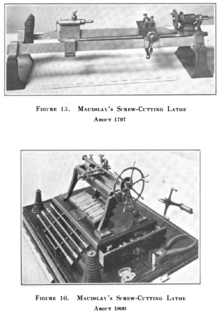

This allowed for the standardization of screw thread sizes for the first time and paved the way for the practical application of interchangeability (an idea that was already taking hold) to nuts and bolts.

Joseph Whitworth's screw thread measurements were adopted as the first (unofficial) national standard by companies around the country in 1841.

By the end of the 19th century, differences in standards between companies were making trade increasingly difficult and strained.

For instance, an iron and steel dealer recorded his displeasure in The Times: "Architects and engineers generally specify such unnecessarily diverse types of sectional material or given work that anything like economical and continuous manufacture becomes impossible.

The national standards were adopted universally throughout the country, and enabled the markets to act more rationally and efficiently, with an increased level of cooperation.

[8] At a regional level (e.g. Europa, the Americas, Africa, etc) or at subregional level (e.g. Mercosur, Andean Community, South East Asia, South East Africa, etc), several Regional Standardization Organizations exist (see also Standards Organization).

Lord Kelvin was an important figure in this process, introducing accurate methods and apparatus for measuring electricity.

In 1857, he introduced a series of effective instruments, including the quadrant electrometer, which cover the entire field of electrostatic measurement.

[20] R. E. B. Crompton became concerned by the large range of different standards and systems used by electrical engineering companies and scientists in the early 20th century.

Many companies had entered the market in the 1890s and all chose their own settings for voltage, frequency, current and even the symbols used on circuit diagrams.

Crompton could see the lack of efficiency in this system and began to consider proposals for an international standard for electric engineering.

Examples include ABNT, AENOR (now called UNE, Spanish Association for Standardization), AFNOR, ANSI, BSI, DGN, DIN, IRAM, JISC, KATS, SABS, SAC, SCC, SIS.

SCC is a Canadian Crown Corporation, DGN is a governmental agency within the Mexican Ministry of Economy, and ANSI and AENOR are a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization with members from both the private and public sectors.

[26] Regulatory authorities can reference voluntary consensus standards to translate internationally accepted criteria into public policy.

[29][30][31] This effect may depend on associated modified consumer choices, strategic product support/obstruction, requirements and bans as well as their accordance with a scientific basis, the robustness and applicability of a scientific basis, whether adoption of the certifications is voluntary, and the socioeconomic context (systems of governance and the economy), with possibly most certifications being so far mostly largely ineffective.

Such standardization is not limited to the domain of electronic devices like smartphones and phone chargers but could also be applied to e.g. the energy infrastructure.

[41] Standardized measurement is used in monitoring, reporting and verification frameworks of environmental impacts, usually of companies, for example to prevent underreporting of greenhouse gas emissions by firms.

It can be done to increase consumer protection, to ensure safety or healthiness or efficiency or performance or sustainability of products.

[45][46] For example, such may be useful for approaches using personal carbon allowances (or similar quota) or for targeted alteration of (ultimate overall) costs.

[49] In the context of defense, standardization has been defined by NATO as The development and implementation of concepts, doctrines, procedures and designs to achieve and maintain the required levels of compatibility, interchangeability or commonality in the operational, procedural, material, technical and administrative fields to attain interoperability.

For example, chairs[47][51][52][53] (see e.g. active sitting and steps of research) could be potentially be designed and chosen using standards that may or may not be based on adequate scientific data.

Standardization is sometimes or could also be used to ensure or increase or enable consumer health protection beyond the workplace and ergonomics such as standards in food, food production, hygiene products, tab water, cosmetics, drugs/medicine,[54] drink and dietary supplements,[55][56] especially in cases where there is robust scientific data that suggests detrimental impacts on health (e.g. of ingredients) despite being substitutable and not necessarily of consumer interest.

[additional citation(s) needed] In the context of assessment, standardization may define how a measuring instrument or procedure is similar to every subjects or patients.

Examples include formalization of judicial procedure in court, and establishing uniform criteria for diagnosing mental disease.

Standardization in this sense is often discussed along with (or synonymously to) such large-scale social changes as modernization, bureaucratization, homogenization, and centralization of society.

[67] Meanwhile, the various links between research and standardization have been identified,[68] also as a platform of knowledge transfer[69] and translated into policy measures (e.g. WIPANO).

[70] The shift to a modularized architecture as a result of standardization brings increased flexibility, rapid introduction of new products, and the ability to more closely meet individual customer's needs.