History of the prime minister of the United Kingdom

The position of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom was not created as a result of a single action; it evolved slowly and organically over three hundred years due to numerous Acts of Parliament, political developments, and accidents of history.

Apart from achieving its intended purpose – to stabilise the budgetary process – it gave the Crown a leadership role in the Commons; and, the lord treasurer assumed a leading position among ministers.

A minority government may be formed as a result of a "hung parliament" in which no single party commands a majority in the House of Commons after a general election or the death, resignation or defection of existing members.

Following the election, Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May negotiated an agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), securing confidence-and-supply support for her minority government.

The last minority government before 2017 was led by Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson for eight months after the February 1974 general election produced a hung parliament.

When George I succeeded to the British throne in 1714, his German ministers advised him to leave the office of Lord High Treasurer vacant because those who had held it in recent years had grown overly powerful, in effect, replacing the sovereign as head of the government.

In 1720, the South Sea Company, created to trade in cotton, agricultural goods and slaves, collapsed, causing the financial ruin of thousands of investors and heavy losses for many others, including members of the royal family.

A year later, the king appointed him First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader of the House of Commons – making him the most powerful minister in the government.

During Great Britain's participation in the Seven Years' War, for example, the powers of government were divided equally between the Duke of Newcastle and William Pitt, leading to them both alternatively being described as Prime Minister.

[27] Lord North, the reluctant head of the King's Government during the American War of Independence, "would never suffer himself to be called Prime Minister, because it was an office unknown to the Constitution".

"[35] In 1905 the position was given some official recognition when the "prime minister" was named in the order of precedence, outranked, among non-royals, only by the archbishops of Canterbury and York, the moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and the lord chancellor.

[37] This law conferred the Chequers Estate owned by Sir Arthur and Lady Lee, as a gift to the Crown for use as a country home for future prime ministers.

Accordingly, Sinn Féin MPs, though ostensively elected to sit in the House of Commons, refused to take their seats in Westminster, and instead assembled in 1919 to proclaim Irish independence and form a revolutionary unicameral parliament for the independent Irish Republic, called Dáil Éireann, which in turn established its own government, called the Ministry of Dáil Éireann.

Most of a parliamentary session beginning on 20 November was devoted to the Act, and Bonar Law pushed through the creation of the Free State in the face of opposition from the "die hards".

After the failure of Lord North's ministry (1770–1782) in March 1782 due to Britain's defeat in the American Revolutionary War and the ensuing vote of no confidence by Parliament, the Marquess of Rockingham reasserted the prime minister's control over the Cabinet.

[49] In practice this means that the sovereign reviews state papers and meets regularly with the prime minister, usually weekly, when he may advise and warn him or her regarding the proposed decisions and actions of His Government.

Informally recognized for over a century as a convention of the constitution, the position of leader of the Opposition was given statutory recognition in 1937 by the Ministers of the Crown Act.

Through patronage, corruption and bribery, the Crown and Lords "owned" about 30% of the seats (called "pocket" or "rotten boroughs") giving them a significant influence in the Commons and in the selection of the prime minister.

But in 1834, Robert Peel, the new Conservative leader, put an end to this threat when he stated in his Tamworth Manifesto that the bill was "a final and irrevocable settlement of a great constitutional question which no friend to the peace and welfare of this country would attempt to disturb".

Mr. Pitt's case in '84 is the nearest analogy; but then the people only confirmed the Sovereign's choice; here every Conservative candidate professed himself in plain words to be Sir Robert Peel's man, and on that ground was elected.

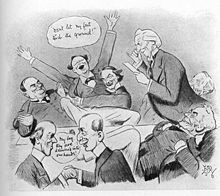

Known by their nicknames "Dizzy" and the "Grand Old Man", their colourful, sometimes bitter, personal and political rivalry over the issues of their time – Imperialism vs. Anti-Imperialism, expansion of the franchise, labour reform, and Irish Home Rule – spanned almost twenty years until Disraeli's death in 1881.

[note 8] Documented by the penny press, photographs and political cartoons, their rivalry linked specific personalities with the premiership in the public mind and further enhanced its status.

Disraeli, who expanded the Empire to protect British interests abroad, cultivated the image of himself (and the Conservative Party) as "Imperialist", making grand gestures such as conferring the title "Empress of India" on Queen Victoria in 1876.

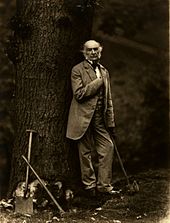

Gladstone, who saw little value in the Empire, proposed an anti-Imperialist policy (later called "Little England"), and cultivated the image of himself (and the Liberal Party) as "man of the people" by circulating pictures of himself cutting down great oak trees with an axe as a hobby.

In his Midlothian campaign – so called because he stood as a candidate for that county – Gladstone spoke in fields, halls and railway stations to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of students, farmers, labourers and middle class workers.

According to Anthony King, "The props in Blair's theatre of celebrity included ... his guitar, his casual clothes ... footballs bounced skilfully off the top of his head ... carefully choreographed speeches and performances at Labour Party conferences.

For most of the history of the Upper House, Lords Temporal were landowners who held their estates, titles, and seats as a hereditary right passed down from one generation to the next – in some cases for centuries.

Representing the landed aristocracy, lords temporal were generally Tory (later Conservative) who wanted to maintain the status quo and resisted progressive measures such as extending the franchise.

In 1906, the Liberal Party, led by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, won an overwhelming victory on a platform that promised social reforms for the working class.

[74] In 1910, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith[note 10] introduced a bill "for regulating the relations between the Houses of Parliament" which would eliminate the Lords' veto power over legislation.