Imperialism

[8] The word “imperialism” was first produced in the 19th century to decry Napoleon III's despotic militarism and his attempts at obtaining political support through foreign military interventions.

"[21] In the 1970s British historians John Gallagher (1919–1980) and Ronald Robinson (1920–1999) argued that European leaders rejected the notion that "imperialism" required formal, legal control by one government over a colonial region.

'"[23] Oron Hale says that Gallagher and Robinson looked at the British involvement in Africa where they "found few capitalists, less capital, and not much pressure from the alleged traditional promoters of colonial expansion.

The colonization of India in the mid-18th century offers an example of this focus: there, the "British exploited the political weakness of the Mughal state, and, while military activity was important at various times, the economic and administrative incorporation of local elites was also of crucial significance" for the establishment of control over the subcontinent's resources, markets, and manpower.

Hobson theorized that domestic social reforms could cure the international disease of imperialism by removing its economic foundation, while state intervention through taxation could boost broader consumption, create wealth, and encourage a peaceful, tolerant, multipolar world order.

Later Marxist theoreticians echo this conception of imperialism as a structural feature of capitalism, which explained the World War as the battle between imperialists for control of external markets.

[38][34] Walter Rodney, in his 1972 How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, proposes the idea that imperialism is a phase of capitalism "in which Western European capitalist countries, the US, and Japan established political, economic, military and cultural hegemony over other parts of the world which were initially at a lower level and therefore could not resist domination.

[45][46] Therefore, Orientalism was the ideological justification of early Western imperialism—a body of knowledge and ideas that rationalized social, cultural, political, and economic control of other, non-white peoples.

The importance of soft power is not lost on authoritarian regimes, which may oppose such influence with bans on foreign popular culture, control of the internet and of unauthorized satellite dishes, etc.

[53] Stephen Howe has summarized his view on the beneficial effects of the colonial empires: At least some of the great modern empires—the British, French, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and even the Ottoman—have virtues that have been too readily forgotten.

[17]: 117 British imperialism in some sparsely-inhabited regions applied a principle now termed Terra nullius (Latin expression which stems from Roman law meaning 'no man's land').

[59]: 11 Across the three major waves of European colonialism (the first in the Americas, the second in Asia and the last in Africa), environmental determinism served to place categorically indigenous people in a racial hierarchy.

Britain made compensating gains in India, Australia, and in constructing an informal economic empire through control of trade and finance in Latin America after the independence of Spanish and Portuguese colonies in about 1820.

However, with the United States and Soviet Union emerging from World War II as the sole superpowers, Britain's role as a worldwide power declined significantly and rapidly.

In the 17th century, following territorial losses on the Scandinavian Peninsula, Denmark-Norway began to develop colonies, forts, and trading posts in West Africa, the Caribbean, and the Indian subcontinent.

As it developed, the new empire took on roles of trade with France, supplying raw materials and purchasing manufactured items, as well as lending prestige to the motherland and spreading French civilization and language as well as Catholicism.

One of the first demands of the emerging nationalist movement after World War II was the introduction of full metropolitan-style education in French West Africa with its promise of equality with Europeans.

Its Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck (1862–90), long opposed colonial acquisitions, arguing that the burden of obtaining, maintaining, and defending such possessions would outweigh any potential benefits.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), Italy occupied British Somaliland, parts of south-eastern France, western Egypt and most of Greece, but then lost those conquests and its African colonies, including Ethiopia, to the invading allied forces by 1943.

As a result, the country turned to imperialism and expansionism in part as a means of compensating for these shortcomings, adopting the national motto "Fukoku kyōhei" (富国強兵, "Enrich the state, strengthen the military").

At first, Japan was in good standing with the victorious Allied powers of World War I, but different discrepancies and dissatisfaction with the rewards of the treaties cooled the relations with them, for example American pressure forced it to return the Shandong area.

Just as Japan's late industrialization success and victory against the Russian Empire was seen as an example among underdeveloped Asia-Pacific nations, the Japanese took advantage of this and promoted among its conquered the goal to jointly create an anti-European "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

[118] Following a long period of military setbacks against European powers, the Ottoman Empire gradually declined, losing control of much of its territory in Europe and Africa.

After Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro gained independence and Britain took colonial control of Cyprus, while Bosnia and Herzegovina were occupied and annexed by Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1908.

Bolshevik leaders had effectively reestablished a polity with roughly the same extent as that empire by 1921, however with an internationalist ideology: Lenin in particular asserted the right to limited self-determination for national minorities within the new territory.

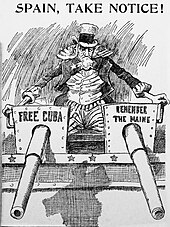

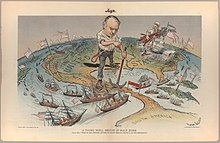

[141][142] Made up of former colonies itself, the early United States expressed its opposition to imperialism, at least in a form distinct from its own Manifest Destiny, through policies such as the Monroe Doctrine.

Beginning in the late 19th and early 20th century, policies such as Theodore Roosevelt's interventionism in Central America and Woodrow Wilson's mission to "make the world safe for democracy"[143] changed all this.

Following the successes of exploratory maritime voyages conducted during the Age of Discovery, Spain committed considerable financial and military resources towards developing a robust navy capable of conducting large-scale, transatlantic expeditionary operations in order to establish and solidify a firm imperial presence across large portions of North America, South America, and the geographic regions comprising the Caribbean basin.

The emergence of the Encomienda system during the 16th–17th centuries in occupied colonies within the Caribbean basin reflects a gradual shift in imperial prioritization, increasingly focusing on large-scale production and exportation of agricultural commodities.

Among historians, there is substantial support in favor of approaching imperialism as a conceptual theory emerging during the 18th–19th centuries, particularly within Britain, propagated by key exponents such as Joseph Chamberlain and Benjamin Disraeli.

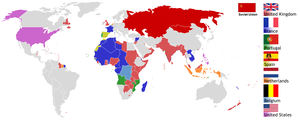

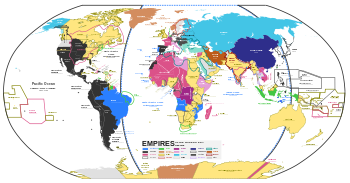

Soviet territories that were never part of Imperial Russia: Tuva , East Prussia , western Ukraine , Kuril Islands

Imperial territories that did not become part of the Soviet Union

Soviet sphere of influence: Warsaw Pact , Mongolia

Soviet military occupation: northern Iran , Manchuria , northern Korea , Xinjiang , Afghanistan