Startling Stories

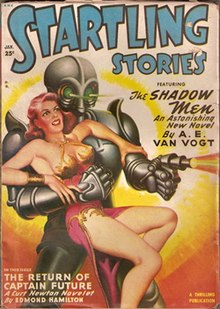

He was known for equipping his heroines with brass bras and implausible costumes, and the public image of science fiction in his day was partly created by his work for Startling and other magazines.

In mid-1952, Standard attempted to change Startling's image by adopting a more sober title typeface and reducing the sensationalism of the covers, but by 1955 the pulp magazine market was collapsing.

[6] Mort Weisinger, the editor of Thrilling Wonder, printed an editorial in February 1938 asking readers for suggestions for a companion magazine.

Response was positive, and the new magazine, titled Startling Stories, was duly launched, with a first issue (pulp-sized, rather than bedsheet-sized, as many readers had requested), dated January 1939.

Other features included a pictorial article on Albert Einstein, and a set of biographical sketches of scientists, titled "Thrills in Science".

[18] Initially the stories for the "Hall of Fame" were chosen by the editor, but soon Weisinger recruited well-known science fiction fans to make the choices.

The target audience was younger readers, and the lead novels were often space operas by well-known pulp writers such as Edmond Hamilton and Manly Wade Wellman.

[7] Weisinger set out to please the younger readers, and when Friend became editor in 1941, he went further in this direction, giving the magazine a strongly juvenile flavor.

For example, Friend introduced "Sergeant Saturn", a character (originally from Thrilling Wonder Stories) who answered readers' letters and appeared in other features in the magazine.

[10][18][24] The interior artwork was initially done by Hans Wessolowski (more usually known as "Wesso"), Mark Marchioni and Alex Schomburg, and occasionally Virgil Finlay.

Bergey's covers were visually striking: in the words of science fiction editor and critic Malcolm Edwards, they typically featured "a rugged hero, a desperate heroine (in either a metallic bikini or a dangerous state of déshabillé) and a hideous alien menace".

[10][15] The brass bra motif came to be associated with Bergey, and his covers did much to create the image of science fiction as it was perceived by the general public.

[25] When Merwin became editor in 1945 he brought changes, but artist Earle K. Bergey retained the creative freedom he had come to expect given his relationship with Standard.

Some argue that Bergey's covers became more realistic,[10][24] and Merwin managed to improve the interiors of Startling to the point of being a serious rival to Astounding, acknowledged leader of the field.

[18] Notable novels that appeared in the late 1940s include Fredric Brown's What Mad Universe and Charles L. Harness's Flight Into Yesterday, later published in book form as The Paradox Men.

Arthur C. Clarke's novel The City and the Stars first saw print in Startling in abbreviated form, in the November 1948 issue, under the title Against the Fall of Night.

After the unusual step of allowing the editor to twice read the work-in-progress and receiving nothing but approval, Asimov delivered a completed draft in September.

[30] However, Startling's editorial policy was more eclectic: it did not limit itself to one kind of story, but printed everything from melodramatic space opera to sociological sf,[18] and Mines had a reputation as having "the most catholic tastes and the fewest inhibitions" of any of the science fiction magazine editors.

[30] In late 1952, Mines published Philip José Farmer's "The Lovers", a taboo-breaking story about aliens who can reproduce only by mating with humans.

Illustrated with an eye-popping cover by Bergey, Farmer's ground-breaking story integrated sex into the plot without being prurient, and was widely praised.

[10][18][19][24] The artwork was also high quality; Virgil Finlay's interior illustrations were "unparalleled", according to science fiction historian Robert Ewald.

[18] Startling's instantly recognizable title logo was redolent of the magazine's pulp roots, and in early 1952 Mines decided to replace it with a more staid typeface.

In 1949 Merlin Press brought out From Off This World, edited by Leo Margulies and Oscar Friend, which included stories that had appeared in the "Hall of Fame" reprint section of the magazine.