Punctuated equilibrium

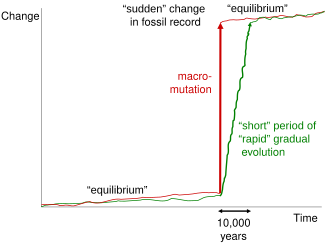

When significant evolutionary change occurs, the theory proposes that it is generally restricted to rare and geologically rapid events of branching speciation called cladogenesis.

[2] In 1972, paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould published a landmark paper developing their theory and called it punctuated equilibria.

[1] Their paper built upon Ernst Mayr's model of geographic speciation,[3] I. M. Lerner's theories of developmental and genetic homeostasis,[4] and their own empirical research.

Punctuated equilibrium originated as a logical consequence of Ernst Mayr's concept of genetic revolutions by allopatric and especially peripatric speciation as applied to the fossil record.

Although the sudden appearance of species and its relationship to speciation was proposed and identified by Mayr in 1954,[3] historians of science generally recognize the 1972 Eldredge and Gould paper as the basis of the new paleobiological research program.

"[15] John Wilkins and Gareth Nelson have argued that French architect Pierre Trémaux proposed an "anticipation of the theory of punctuated equilibrium of Gould and Eldredge.

New and even beneficial mutations are diluted by the population's large size and are unable to reach fixation, due to such factors as constantly changing environments.

In addition, pressure from natural selection is especially intense, as peripheral isolated populations exist at the outer edges of ecological tolerance.

This hypothesis was alluded to by Mayr in the closing paragraph of his 1954 paper: Rapidly evolving peripherally isolated populations may be the place of origin of many evolutionary novelties.

Their isolation and comparatively small size may explain phenomena of rapid evolution and lack of documentation in the fossil record, hitherto puzzling to the palaeontologist.

"[46] Punctuated equilibrium has also been cited as contributing to the hypothesis that species are Darwinian individuals, and not just classes, thereby providing a stronger framework for a hierarchical theory of evolution.

[50][51][52][53] This interpretation has frequently been used by creationists to characterize the weakness of the paleontological record, and to portray contemporary evolutionary biology as advancing neo-saltationism.

"[57] Simpson's conjecture was that according to the geological record, on very rare occasions evolution would proceed very rapidly to form entirely new families, orders, and classes of organisms.

Despite such differences between the two models, earlier critiques—from such eminent commentators as Sewall Wright as well as Simpson himself—have argued that punctuated equilibrium is little more than quantum evolution relabeled.

To this end, Gould later commented that "Most of our paleontological colleagues missed this insight because they had not studied evolutionary theory and either did not know about allopatric speciation or had not considered its translation to geological time.

[14] Richard Dawkins dedicates a chapter in The Blind Watchmaker to correcting, in his view, the wide confusion regarding rates of change.

His first point is to argue that phyletic gradualism—understood in the sense that evolution proceeds at a single uniform speed, called "constant speedism" by Dawkins—is a "caricature of Darwinism"[65] and "does not really exist".

Eldredge and Gould, proposing that evolution jumps between stability and relative rapidity, are described as "discrete variable speedists", and "in this respect they are genuinely radical.

[69] However, the punctuational equilibrium model may still be inferred from both the observation of stasis and examples of rapid and episodic speciation events documented in the fossil record.

[74] In his book Darwin's Dangerous Idea, philosopher Daniel Dennett is especially critical of Gould's presentation of punctuated equilibrium.

[75] Gould responded to Dennett's claims in The New York Review of Books,[76] and in his technical volume The Structure of Evolutionary Theory.

[77] English professor Heidi Scott argues that Gould's talent for writing vivid prose, his use of metaphor, and his success in building a popular audience of nonspecialist readers altered the "climate of specialized scientific discourse" favorably in his promotion of punctuated equilibrium.

He privately expressed concern, noting in the margin of his 1844 Essay, "Better begin with this: If species really, after catastrophes, created in showers world over, my theory false.

[85][90] Recent work in developmental biology has identified dynamical and physical mechanisms of tissue morphogenesis that may underlie abrupt morphological transitions during evolution.

Consequently, consideration of mechanisms of phylogenetic change that have been found in reality to be non-gradual is increasingly common in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, particularly in studies of the origin of morphological novelty.

[92] Separately, recent work using computational phylogenetic methods claims to show that punctuational bursts play an important factor when languages split from one another, accounting for anywhere from 10 to 33% of the total divergence in vocabulary.