Steam engine

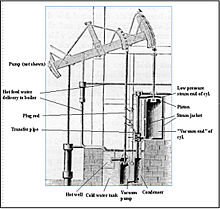

[12] The Spanish inventor Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont received patents in 1606 for 50 steam-powered inventions, including a water pump for draining inundated mines.

[17] Bento de Moura Portugal introduced an improvement of Savery's construction "to render it capable of working itself", as described by John Smeaton in the Philosophical Transactions published in 1751.

It was employed for draining mine workings at depths originally impractical using traditional means, and for providing reusable water for driving waterwheels at factories sited away from a suitable "head".

For early use of the term Van Reimsdijk[31] refers to steam being at a sufficiently high pressure that it could be exhausted to atmosphere without reliance on a vacuum to enable it to perform useful work.

Compound engines exhausted steam into successively larger cylinders to accommodate the higher volumes at reduced pressures, giving improved efficiency.

These stages were called expansions, with double- and triple-expansion engines being common, especially in shipping where efficiency was important to reduce the weight of coal carried.

[39] An early working model of a steam rail locomotive was designed and constructed by steamboat pioneer John Fitch in the United States probably during the 1780s or 1790s.

The first full-scale working railway steam locomotive was built by Richard Trevithick in the United Kingdom and, on 21 February 1804, the world's first railway journey took place as Trevithick's steam locomotive hauled 10 tones of iron, 70 passengers and five wagons along the tramway from the Pen-y-darren ironworks, near Merthyr Tydfil to Abercynon in south Wales.

Trevithick visited the Newcastle area later in 1804 and the colliery railways in north-east England became the leading centre for experimentation and development of steam locomotives.

Steam locomotives continued to be manufactured until the late twentieth century in places such as China and the former East Germany (where the DR Class 52.80 was produced).

[48][49] The widely used reciprocating engine typically consisted of a cast-iron cylinder, piston, connecting rod and beam or a crank and flywheel, and miscellaneous linkages.

When coal is used, a chain or screw stoking mechanism and its drive engine or motor may be included to move the fuel from a supply bin (bunker) to the firebox.

[59] The governor was improved over time and coupled with variable steam cut off, good speed control in response to changes in load was attainable near the end of the 19th century.

In one case (the first type of Vauclain compound), the pistons worked in the same phase driving a common crosshead and crank, again set at 90° as for a two-cylinder engine.

This is partly due to the harsh railway operating environment and limited space afforded by the loading gauge (particularly in Britain, where compounding was never common and not employed after 1930).

[65] In most reciprocating piston engines, the steam reverses its direction of flow at each stroke (counterflow), entering and exhausting from the same end of the cylinder.

The combined setup gave a fair approximation of the ideal events, at the expense of increased friction and wear, and the mechanism tended to be complicated.

[citation needed] The above effects are further enhanced by providing lead: as was later discovered with the internal combustion engine, it has been found advantageous since the late 1830s to advance the admission phase, giving the valve lead so that admission occurs a little before the end of the exhaust stroke in order to fill the clearance volume comprising the ports and the cylinder ends (not part of the piston-swept volume) before the steam begins to exert effort on the piston.

The aim of the uniflow is to remedy this defect and improve efficiency by providing an additional port uncovered by the piston at the end of each stroke making the steam flow only in one direction.

[citation needed] Steam turbines provide direct rotational force and therefore do not require a linkage mechanism to convert reciprocating to rotary motion.

Some non-condensing direct-drive locomotives did meet with some success for long haul freight operations in Sweden and for express passenger work in Britain, but were not repeated.

Many such engines have been designed, from the time of James Watt to the present day, but relatively few were actually built and even fewer went into quantity production; see link at bottom of article for more details.

The major problem is the difficulty of sealing the rotors to make them steam-tight in the face of wear and thermal expansion; the resulting leakage made them very inefficient.

However, the arrival of electricity on the scene, and the obvious advantages of driving a dynamo directly from a high-speed engine, led to something of a revival in interest in the 1880s and 1890s, and a few designs had some limited success.

[citation needed] Steam engines possess boilers and other components that are pressure vessels that contain a great deal of potential energy.

While variations in standards may exist in different countries, stringent legal, testing, training, care with manufacture, operation and certification is applied to ensure safety.

[citation needed] Failure modes may include: Steam engines frequently possess two independent mechanisms for ensuring that the pressure in the boiler does not go too high; one may be adjusted by the user, the second is typically designed as an ultimate fail-safe.

If the water level drops, such that the temperature of the firebox crown increases significantly, the lead melts and the steam escapes, warning the operators, who may then manually suppress the fire.

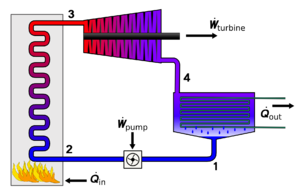

[19] The thermodynamic concepts of the Rankine cycle did give engineers the understanding needed to calculate efficiency which aided the development of modern high-pressure and -temperature boilers and the steam turbine.

By condensing the fluid, the work required by the pump consumes only 1% to 3% of the turbine (or reciprocating engine) power and contributes to a much higher efficiency for a real cycle.

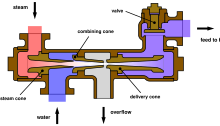

The poppet valves are controlled by the rotating camshaft at the top. High-pressure steam enters, red, and exhausts, yellow.