Stellar structure

Stellar structure models describe the internal structure of a star in detail and make predictions about the luminosity, the color and the future evolution of the star.

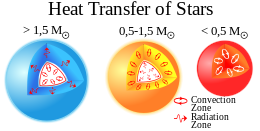

Different layers of the stars transport heat up and outwards in different ways, primarily convection and radiative transfer, but thermal conduction is important in white dwarfs.

Convection is the dominant mode of energy transport when the temperature gradient is steep enough so that a given parcel of gas within the star will continue to rise if it rises slightly via an adiabatic process.

[1] In regions with a low temperature gradient and a low enough opacity to allow energy transport via radiation, radiation is the dominant mode of energy transport.

The outer portion of solar mass stars is cool enough that hydrogen is neutral and thus opaque to ultraviolet photons, so convection dominates.

In massive stars (greater than about 1.5 M☉), the core temperature is above about 1.8×107 K, so hydrogen-to-helium fusion occurs primarily via the CNO cycle.

In the CNO cycle, the energy generation rate scales as the temperature to the 15th power, whereas the rate scales as the temperature to the 4th power in the proton-proton chains.

In the outer portion of the star, the temperature gradient is shallower but the temperature is high enough that the hydrogen is nearly fully ionized, so the star remains transparent to ultraviolet radiation.

[3] The simplest commonly used model of stellar structure is the spherically symmetric quasi-static model, which assumes that a star is in a steady state and that it is spherically symmetric.

[4] In forming the stellar structure equations (exploiting the assumed spherical symmetry), one considers the matter density

The star is assumed to be in local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) so the temperature is identical for matter and photons.

is the luminosity produced in the form of neutrinos (which usually escape the star without interacting with ordinary matter) per unit mass.

Outside the core of the star, where nuclear reactions occur, no energy is generated, so the luminosity is constant.

In the case of radiative energy transport, appropriate for the inner portion of a solar mass main sequence star and the outer envelope of a massive main sequence star, where

The case of convective energy transport does not have a known rigorous mathematical formulation, and involves turbulence in the gas.

Convective energy transport is usually modeled using mixing length theory.

This treats the gas in the star as containing discrete elements which roughly retain the temperature, density, and pressure of their surroundings but move through the star as far as a characteristic length, called the mixing length.

[5] For a monatomic ideal gas, when the convection is adiabatic, meaning that the convective gas bubbles don't exchange heat with their surroundings, mixing length theory yields where

[6] Also required are the equations of state, relating the pressure, opacity and energy generation rate to other local variables appropriate for the material, such as temperature, density, chemical composition, etc.

It is calculated for various compositions at specific densities and temperatures and presented in tabular form.

[7] Stellar structure codes (meaning computer programs calculating the model's variables) either interpolate in a density-temperature grid to obtain the opacity needed, or use a fitting function based on the tabulated values.

A similar situation occurs for accurate calculations of the pressure equation of state.

[6][8] Combined with a set of boundary conditions, a solution of these equations completely describes the behavior of the star.

Typical boundary conditions set the values of the observable parameters appropriately at the surface (

Although nowadays stellar evolution models describe the main features of color–magnitude diagrams, important improvements have to be made in order to remove uncertainties which are linked to the limited knowledge of transport phenomena.

[citation needed] Some research teams are developing simplified modelling of turbulence in 3D calculations.

The above simplified model is not adequate without modification in situations when the composition changes are sufficiently rapid.

The equation of hydrostatic equilibrium may need to be modified by adding a radial acceleration term if the radius of the star is changing very quickly, for example if the star is radially pulsating.

[9] Also, if the nuclear burning is not stable, or the star's core is rapidly collapsing, an entropy term must be added to the energy equation.