Stellation

A regular star polygon is represented by its Schläfli symbol {n/m}, where n is the number of vertices, m is the step used in sequencing the edges around it, and m and n are coprime (have no common factor).

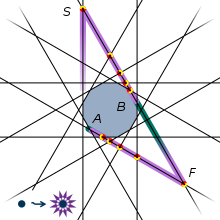

A common method of finding stellations involves selecting one or more cell types.

This can lead to a huge number of possible forms, so further criteria are often imposed to reduce the set to those stellations that are significant and unique in some way.

A set of cells forming a closed layer around its core is called a shell.

Generalising Miller's rules there are: Seventeen of the nonconvex uniform polyhedra are stellations of Archimedean solids.

Miller proposed a set of rules for defining which stellation forms should be considered "properly significant and distinct".

For example many have hollow centres where the original faces and edges of the core polyhedron are entirely missing: there is nothing left to be stellated.

On the other hand, Kepler's method also yields stellations which are forbidden by Miller's rules since their cells are edge- or vertex-connected, even though their faces are single polygons.

They are based on combining parts within the stellation diagram in certain ways, and don't take into account the topology of the resulting faces.

Most progress has been made based on the notion that stellation is the reciprocal or dual process to facetting, whereby parts are removed from a polyhedron without creating any new vertices.

This is understandable if one is devising a general algorithm suitable for use in a computer program, but is otherwise not particularly helpful.

John Conway devised a terminology for stellated polygons, polyhedra and polychora (Coxeter 1974).

Wenninger's figures occurred as duals of the uniform hemipolyhedra, where the faces that pass through the center are sent to vertices "at infinity".

[1] The Italian Renaissance artist Paolo Uccello created a floor mosaic showing a small stellated dodecahedron in the Basilica of St Mark, Venice, c. 1430.